“In the American South, we don’t talk about slavery. We don’t have monuments and memorials that confront the legacy of lynching. We haven’t really confronted the difficulties of segregation. And because of that, I think we are still burdened by that history.” – Bryan Stevenson, EJI executive director

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice opened to the public on April 26 near downtown Montgomery, Alabama and became the first memorial dedicated to the legacy of enslaved black people, people terrorized by lynching, African Americans humiliated by racial segregation and Jim Crow, and people of color burdened with contemporary presumptions of guilt and police violence.

Work on the memorial began in 2010 when Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) staff began investigating thousands of racial terror lynchings in the American South, many of which had never been documented. EJI was interested not only in lynching incidents, but in understanding the terror and trauma this sanctioned violence against the black community created. Six million black people fled the South as refugees and exiles as a result of these “racial terror lynchings.”

This research ultimately produced Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror in 2015 which documented thousands of racial terror lynchings in twelve states. Since the report’s release, EJI staff have embarked on a project to memorialize this history by visiting hundreds of lynching sites beyond the Deep South, collecting soil, and erecting public markers, in an effort to reshape the cultural landscape with monuments and memorials that more truthfully and accurately reflect our history.

“Our nation’s history of racial injustice casts a shadow across the American landscape,” said Stevenson. “This shadow cannot be lifted until we shine the light of truth on the destructive violence that shaped our nation, traumatized people of color, and compromised our commitment to the rule of law and to equal justice.”

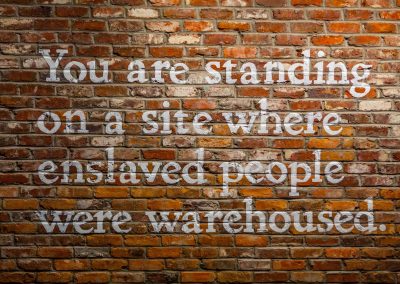

The Memorial for Peace and Justice was conceived with the hope of creating a sober, meaningful site where people can gather and reflect on America’s history of racial inequality. EJI partnered with artists like Kwame Akoto-Bamfo whose sculpture on slavery confronts visitors when they first enter the memorial. EJI then leads visitors on a journey from slavery, through lynching and racial terror, with text, narrative, and monuments to the lynching victims in America.

In the center of the site, visitors encounter a memorial square, created with assistance from the Mass Design Group. The memorial experience continues through the civil rights era made visible with a sculpture by Dana King dedicated to the women who sustained the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Finally, the memorial journey ends with contemporary issues of police violence and racially biased criminal justice expressed in a final work created by Hank Willis Thomas. The memorial displays writing from Toni Morrison, words from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and a reflection space in honor of Ida B. Wells.

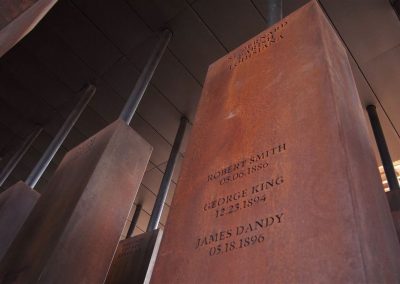

Set on a six-acre site, the memorial uses sculpture, art, and design to contextualize racial terror. The site includes a memorial square with 800 six-foot monuments to symbolize thousands of racial terror lynching victims in the United States and the counties and states where this terrorism took place.

The memorial structure on the center of the site is constructed of over 800 corten steel monuments, one for each county in the United States where a racial terror lynching took place. The names of the lynching victims are engraved on the columns. The memorial is more than a static monument. In the six-acre park surrounding the memorial is a field of identical monuments, waiting to be claimed and installed in the counties they represent. Over time, the national memorial will serve as a report on which parts of the country have confronted the truth of this terror and which have not.

Lynching in America

In the report, Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror, EJI documented more than 4400 lynchings of black people in the United States between 1877 and 1950. EJI identified 800 more lynchings than had previously been recognized.

Racial terror lynchings were violent and public acts of torture that traumatized black people throughout the country and were largely tolerated by state and federal officials. Lynchings in the American South were not isolated hate crimes committed by rogue vigilantes. Lynching was targeted racial violence at the core of a systematic campaign of terror perpetuated in furtherance of an unjust social order. These lynchings were terrorism.

The lynching era left thousands dead; it significantly marginalized black people in the country’s political, economic, and social systems; and it fueled a massive migration of black refugees out of the South. In addition, lynching – and other forms of racial terrorism – inflicted deep traumatic and psychological wounds on survivors, witnesses, family members, and the entire African American community.

Building a Memorial to Victims of Racial Terror

EJI believed that publicly confronting the truth about our history is the first step towards recovery and reconciliation. As such, a history of racial injustice must be acknowledged, and mass atrocities and abuse must be recognized and remembered, before a society can recover from mass violence. Public commemoration plays a significant role in prompting community-wide reconciliation.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice provides a sacred space for truth-telling and reflection about racial terrorism and its legacy. Modeled on important projects used to overcome difficult histories of genocide, apartheid, and horrific human rights abuses in other countries, EJI’s sites are designed to promote a more hopeful commitment to racial equality and just treatment of all people.

The Evolution of Slavery

To justify the brutal, dehumanizing institution of slavery in America, its advocates created a myth of racial difference. Stereotypes and false characterizations of black people were created to defend their permanent enslavement as “most necessary to the well-being of the negro” – an act of kindness that reinforced white supremacy. The formal abolition of slavery did nothing to overcome the harmful ideas created to defend it, and so slavery did not end: it evolved.

In the decades that followed, these beliefs in racial hierarchy took new expression in convict leasing, lynching, and other forms of racial terrorism that forced the exodus of millions of black Americans to the North and West, where the myth of racial difference manifested in urban ghettos and generational poverty.

Racial subordination was codified and enforced by violence in the era of Jim Crow and segregation, as the nation and its leaders allowed black people to be burdened, beaten, and marginalized throughout the 20th century.

Progress towards civil rights for African Americans was made in the 1960s, but the myth of racial inferiority was not eradicated. Black Americans were vulnerable to a new era of racial bias and abuse of power wielded by our contemporary criminal justice system. Mass incarceration has had devastating consequences for people of color: at the dawn of the 21st century, one in three black boys are projected to go to jail or prison in his lifetime.

© Photo

Equal Justice Initiative (EJI)