Wisconsin’s wild bees are a small but mighty part of the ecosystem for native plants and agriculture alike. And they’re in trouble.

According to the Wisconsin Pollinator Plan issued by the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Protection in April 2016, pollinator-dependent crops that include cranberries, apples, cherries and green beans account for over $55 million in annual production around the state. The value of these insect pollinators to native wild plants is harder to quantify.

But environmental threats to native bumble bees, such as habitat loss, extreme weather and exposure to pesticides or pathogens, mean that many species may be in decline. One, the rusty-patched bumble bee (Bombus affinis), is included on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s endangered list.

“Of our 20 native bumble bees, at least half are in need of conservation assistance or more information because we know so little about them,” said Eva Lewandowski, the coordinator of citizen-based monitoring for the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resource’s Bureau of Natural Heritage Conservation.

The Wisconsin Bumble Bee Brigade is training volunteers across the state to photograph and identify bees, then share their field work with researchers and the public. The project’s stated objectives are to develop an accurate map of species distributions, identify species-habitat associations, assess habitat conditions and determine conservation threats, determine baseline population status and monitor trends over time.

Launched in the spring of 2018, the Brigade is a project of the DNR and Wisconsin Aquatic and Terrestrial Resources Directory, and part of the Wisconsin Citizen-based Monitoring Network, a group of projects in which volunteers can help scientists gather data about the state’s wildlife and waters. It is one of the more than 20 citizen-based monitoring programs in Wisconsin.

“A lot of people are concerned about pollinators these days. They’re worried about health of ecosystems and this is one way they can help out,” said Lewandowski, who helped launch the Brigade.

“There are a lot of people who just love to do nature photography. For them to go out and do something they already enjoy doing, and share the photos, I think that’s going to be a big driver for some of our volunteers,” she added.

Gathering data about bumble bees

Claudio Gratton, a professor of entomology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said his research will benefit from the data collected by volunteers.

“One of the key things that we as bee researchers have been struggling with is getting at this question that everyone wants to know, and that is ‘are bees in decline?’ We know about honeybees,” Gratton said. “We know almost nothing about the fate of native wild bees in our environment. We don’t have historical data. That’s a real basic and critical piece of information that we we want to know.”

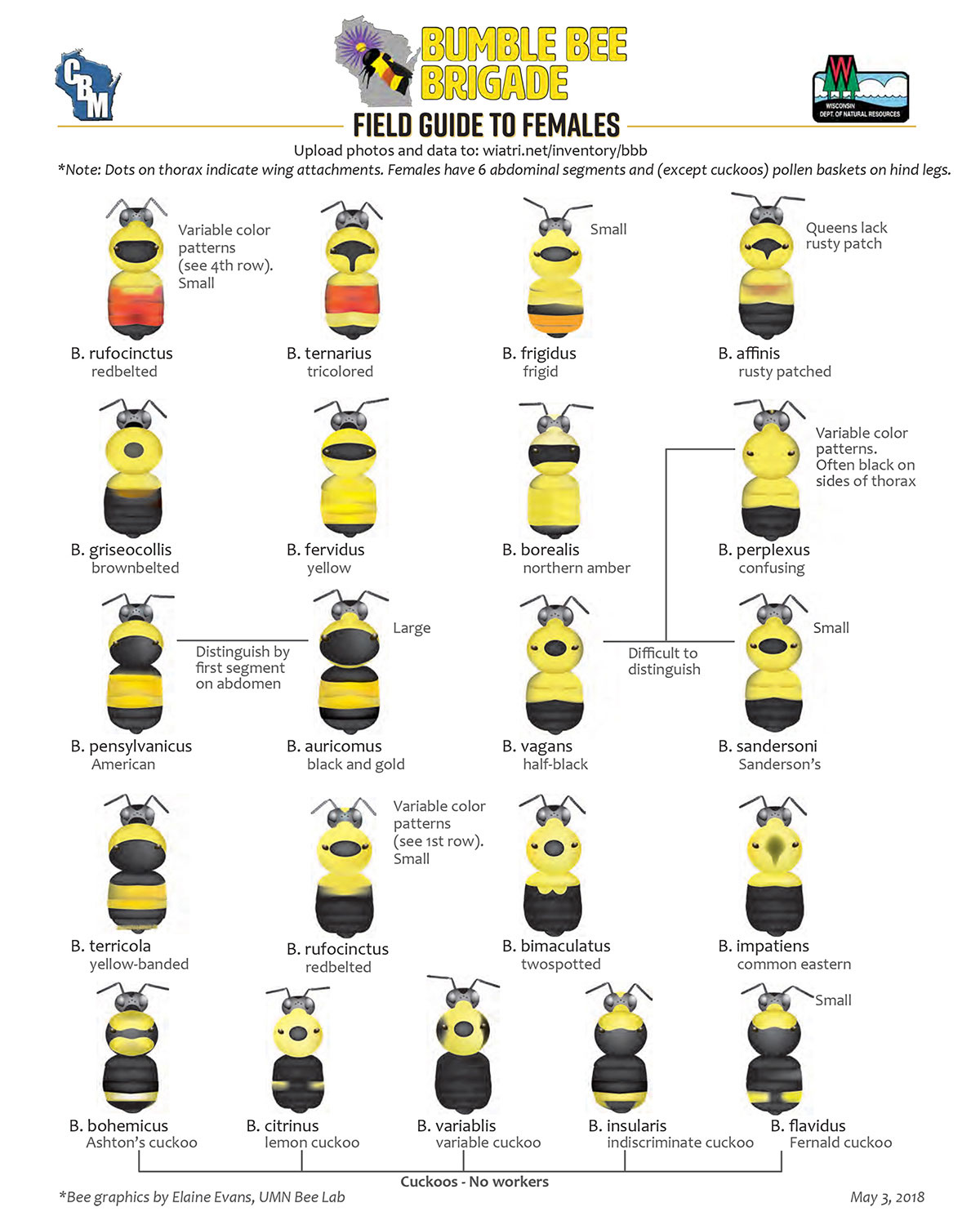

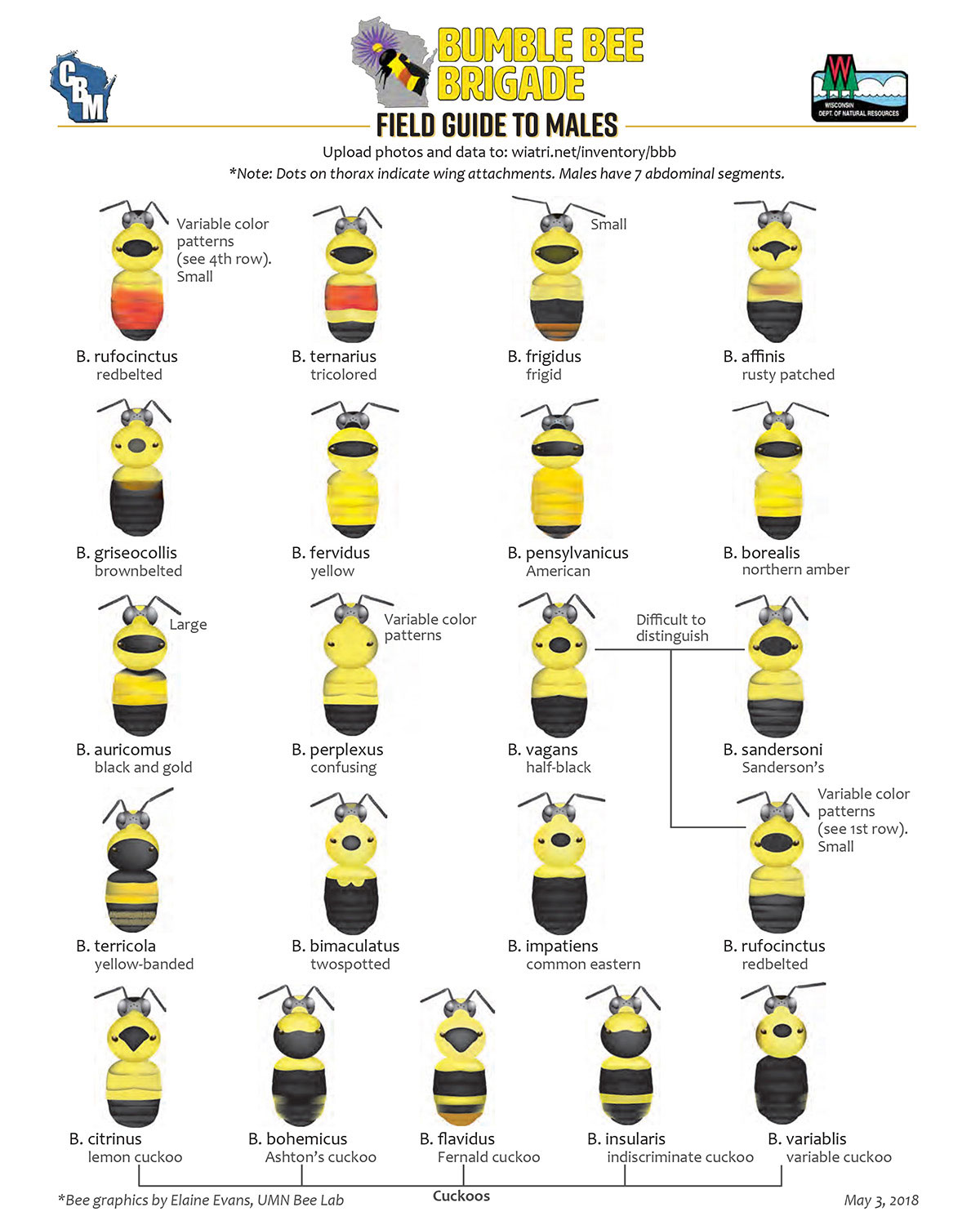

Volunteers with the Wisconsin Bumble Bee Brigade receive training on bumble bee biology and follow a visual field guide to identifying the bees they photograph. Working alone or in teams on a small-area survey of about 100 feet in diameter, they also collect and submit data on the exact location where they conducted their fieldwork, even if they didn’t spot any bees.

“We are asking people to do small-area surveys in almost any habitat,” Lewandowski said. “The goal of the project is to gather information about how habitat might influence the number and type of bees that are there. We don’t want people to just go to prime bumble bee habitat. Go to a roadside. Go to your backyard. If people want to get started, go wherever it is easy to get to.”

So long as there are appropriate plants around for the bees, that is. “You need to find something they’ll be stopping for. You won’t be seeing bees in a parking lot,” Lewandowski noted.

Gratton hopes that volunteers will venture off the beaten path on behalf of bee research.

“As a landscape ecologist, I wish I could have my eyes all over the landscape, but we just can’t do it alone,” Gratton said. “This is an opportunity to get data and make sense out of the data. It’s really valuable.”

The downside of citizen (or civic) science, however, is that volunteers sometimes make mistakes, so the project tries to minimize errors through training and expert review of all the photographs and data after they are uploaded to the website, Gratton said.

Susan Carpenter, a native plant gardener with the University of Wisconsin-Madison Arboretum, has also been advising the project. She started a similar program there in 2011 after a bee researcher from the University of California-Davis shared a photograph of a rusty-patched bumble bee he had taken while on a visit to the arboretum on Madison’s south side.

“A little thing can cause a brand-new effort,” Carpenter said. “That’s a story about how one picture could change a lot.”

The species, in decline across eastern North America, was listed in early 2017. It was the first bumble bee to be included on the endangered list.

There are other citizen science initiatives focused on bees, such as Bumble Bee Watch, a project that records sightings across North America, and has been used to document sightings at the UW Arboretum. However, the statewide focus of the Brigade is very useful, Carpenter said.

“It’s going to be a very good way of having a portal that will give the DNR information on the distribution of bumble bees for conservation and land management,” she said.

“We have a lot of data about the Arboretum,” Carpenter said. “The point of all of these is to educate people to go out start to pay attention and start to monitor and compile these data together so these larger patterns can be uncovered. Then new questions can get asked.”

Any reports of the rusty-patched bumble bee will be shared with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Lewandowski said. All of the data will be available to the public.

Participation in the first year of the project is limited, as the Wisconsin Bumble Bee Brigade recruits volunteers and tests out its training and data collection methods. Several trainings are being held around Wisconsin in June and July.

“In order to see some of these patterns, you can’t just do this study in your own backyard. It’s patterns that play out over an entire region or landscape. The only way to get it is to engage with others,” Gratton said.

Michelle Johnson

Originally published on WisContext as Wisconsin Bumble Bee Brigade Tracks Species, 1 Photo At A Time