By Chunjie Zhang, Associate Professor of German, University of California, Davis

During one of my daily walks with my toddler, when we passed his favorite playground, I noticed a new sign warning that the coronavirus survives on all kinds of surfaces and that we should no longer use the playground. Since then, I’ve taken great pains to prevent him from touching things.

This has not been easy. He loves to squeeze bike racks and graze tree trunks, jostle bushes and knock on picnic tables. He likes to run his fingers against bars around a swimming pool and pet the chickens at the neighborhood coop.

Whenever I bat his hand away or try to distract him from potentially absorbing these dreaded, invisible germs, I wonder: What is being lost? How can he possibly indulge his curiosity and learn about the world without his sense of touch?

I find myself thinking about Johann Gottfried Herder, an 18th-century German philosopher who published a treatise on the sense of touch in 1778.

“Go into a nursery and see how the young child who is constantly gathering experience reaches out, grasping, lifting, weighing, touching and measuring things,” he wrote. In doing so, the child acquires “the most primary and necessary concepts, such as body, shape, size, space and distance.”

During the European Enlightenment, sight was considered by many to be the most important sense because it could perceive light, and light also symbolized scientific fact and philosophical truth. However, some thinkers, such as Herder and Denis Diderot, questioned sight’s predominance. Herder writes that “sight reveals merely shapes, but touch alone reveals bodies: that everything that has form is known only through the sense of touch and that sight reveals only … surfaces exposed to light.”

To Herder, our knowledge of the world – our relentless curiosity – is fundamentally transmitted and satiated through our skin. Herder argues that blind people are, in fact, privileged; they’re able to explore via touch without distraction and are “able to develop concepts of the properties of bodies that are far more complete than those acquired by the sighted.”

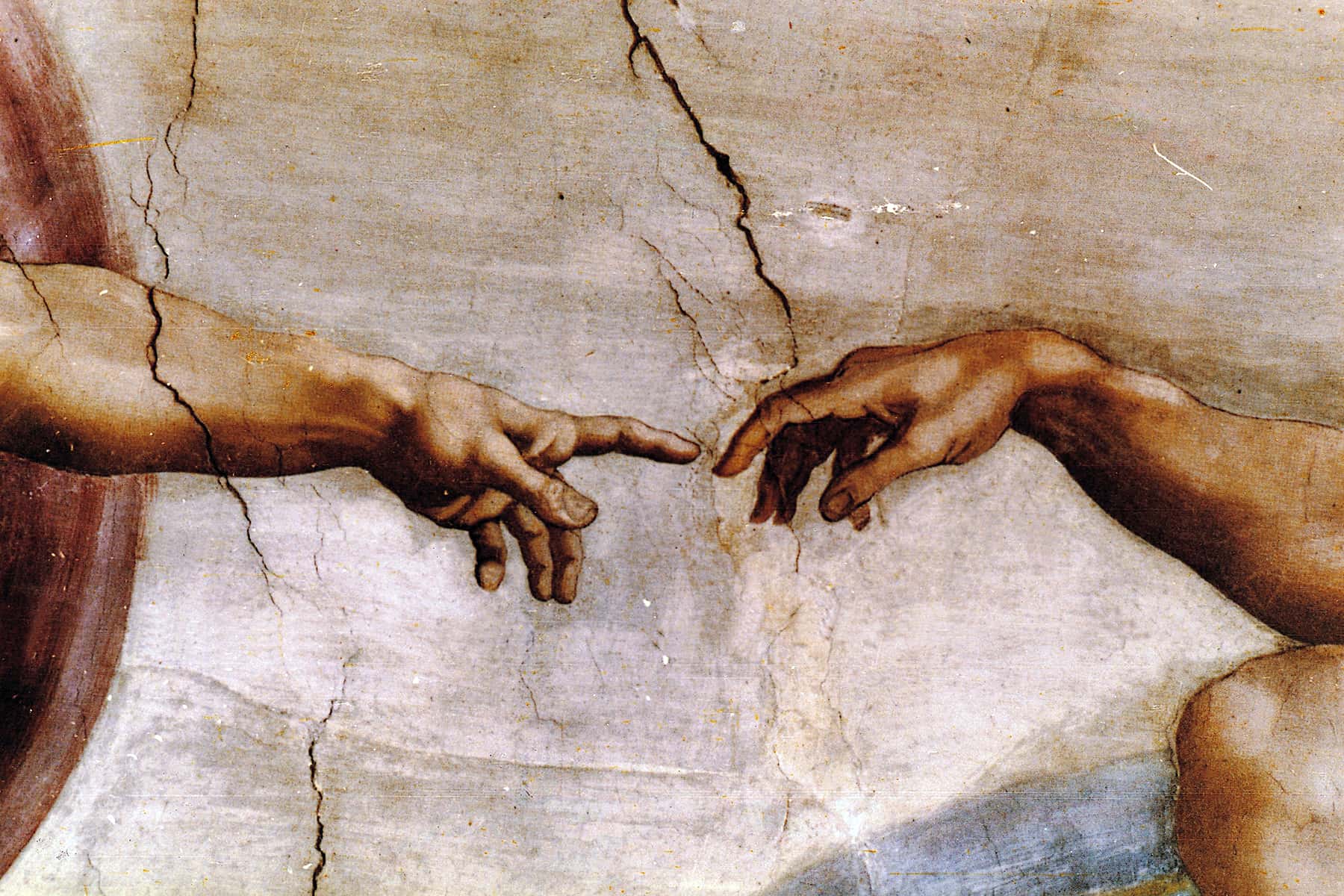

For Herder, touch was the only way to understand the form of things and grasp the shape of bodies. Herder changes René Descartes’ statement “I think, therefore I am” and claims: We touch, therefore we know. We touch, therefore we are.

Herder was onto something. Centuries later, neuroscientists like David Linden have been able to map out the power of touch – the first sense, he notes in his book “Touch: The Science of Hand, Heart, and Mind,” to develop in utero.

Linden writes that our skin is a social organ that cultivates cooperation, improves health and enhances development. He points to research showing that celebratory hugging among professional basketball players improves team performance, that premature babies are more likely to survive if they’re regularly held by their parents instead of being kept solely in incubators and that children severely deprived of touch end up with more developmental problems.

During this period of social distancing, what sort of void has been created? In our social lives, touches are often subtle and brief – a quick handshake or hug. Yet it seems as though these brief encounters contribute mightily to our emotional well-being.

As a professor, I know it’s been a huge advantage to have digital technology that enables remote learning. But my students are missing out on the little touches, intentional or accidental, from their friends and classmates, whether it’s in the classroom, in dining halls or in their dorms.

Perhaps not surprisingly, touch plays a bigger role in some cultures than in others. Psychologist Sidney Jourard observed the behavior of Puerto Ricans in a San Juan coffee shop and found that they touched one another an average of 180 times per hour. I wonder how they’re handling social distancing. Residents of Gainesville, Florida, are probably having an easier time; Jourard found they only touched twice per hour in a coffee shop.

Social distancing is crucial. But I am already pining for the day when we can all engage with the world unimpeded, touching without anxiety or hesitation. We are more impoverished without it.

Originally published on The Conversation as What’s lost when we’re too afraid to touch the world around us?

Support evidence-based journalism with a tax-deductible donation today, make a contribution to The Conversation.