On March 4, 1858, South Carolina senator James Henry Hammond rose to his feet to explain to the Senate how society worked. “In all social systems,” he said, “there must be a class to do the menial duties, to perform the drudgery of life.” That class, he said, needed little intellect and little skill, but it should be strong, docile, and loyal.

“Such a class you must have, or you would not have that other class which leads progress, civilization and refinement,” Hammond said. His workers were the “mud-sill” on which society rested, the same way that a stately house rested on wooden sills driven into the mud.

He told his northern colleagues that the South had perfected this system by enslavement based on race, while northerners pretended that they had abolished slavery. “Aye, the name, but not the thing,” he said. “[Y]our whole hireling class of manual laborers and ‘operatives,’ as you call them, are essentially slaves.”

While southern leaders had made sure to keep their enslaved people from political power, Hammond said, he warned that northerners had made the terrible mistake of giving their “slaves” the vote. As the majority, they could, if they only realized it, control society. Then “where would you be?” he asked. “Your society would be reconstructed, your government overthrown, your property divided, not…with arms…but by the quiet process of the ballot-box.”

He warned that it was only a matter of time before workers took over northern cities and began slaughtering men of property.

Hammond’s vision was of a world divided between the haves and the have-nots, where men of means commandeered the production of workers and justified that theft with the argument that such a concentration of wealth would allow superior men to move society forward.

It was a vision that spoke for the South’s wealthy planter class—enslavers who held more than 50 of their Black neighbors in bondage and made up about 1% of the population—but such a vision didn’t even speak for the majority of white southerners, most of whom were much poorer than such a vision suggested.

And it certainly did not speak for northerners, to whom Hammond’s vision of a society divided between dim drudges and the rich and powerful was both troubling and deeply insulting.

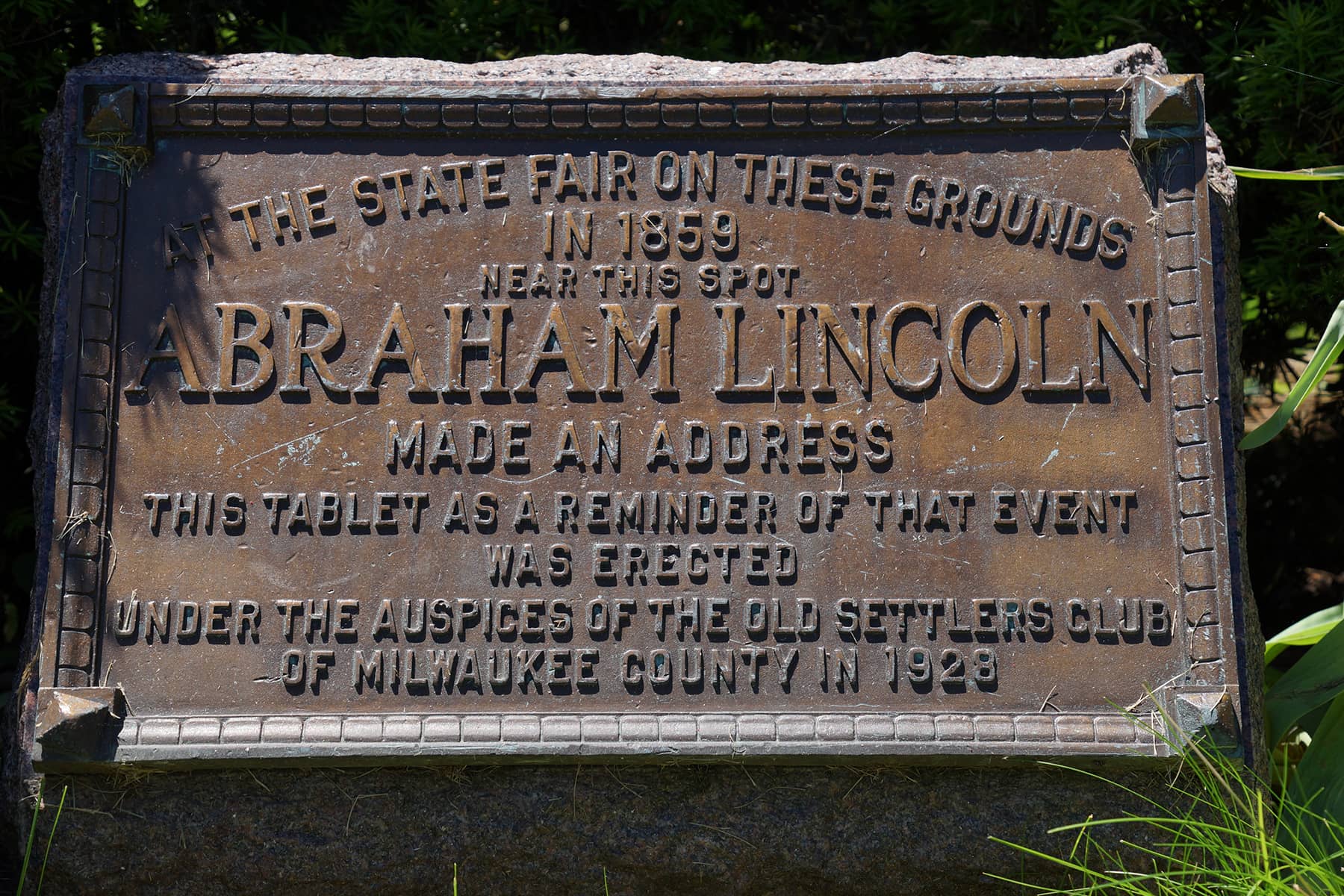

On September 30, 1859, at the Wisconsin State Agricultural Fair, rising politician Abraham Lincoln answered Hammond’s vision of a society dominated by a few wealthy men. While the South Carolina enslaver argued that labor depended on capital to spur men to work, either by hiring them or enslaving them, Lincoln said there was an entirely different way to see the world.

Representing an economy in which most people worked directly on the land or water to pull wheat into wagons and fish into barrels, Lincoln believed that “[l]abor is prior to, and independent of, capital; that, in fact, capital is the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed — that labor can exist without capital, but that capital could never have existed without labor. Hence they hold that labor is the superior—greatly the superior of capital.”

A man who had, himself, worked his way up from poverty to prominence – while Hammond had married into money, Lincoln went on: “[T]he opponents of the ‘mud-sill’ theory insist that there is not … any such things as the free hired laborer being fixed to that condition for life.”

And then Lincoln articulated what would become the ideology of the fledgling Republican Party:

“The prudent, penniless beginner in the world, labors for wages awhile, saves a surplus with which to buy tools or land, for himself; then labors on his own account for another while, and at length hires another new beginner to help him. This, say its advocates, is free labor—the just and generous, and prosperous system, which opens the way for all—gives hope to all, and energy and progress, and improvement of condition to all.”

In such a worldview, everyone shared a harmony of interest. What was good for the individual worker was, ultimately, good for everyone. There was no conflict between labor and capital; capital was simply “pre-exerted labor.” Except for a few unproductive financiers and those who wasted their wealth on luxuries, everyone was part of the same harmonious system.

The protection of property was crucial to this system, but so was opposition to great accumulations of wealth. Levelers who wanted to confiscate property would upset this harmony, as Hammond warned, but so would rich men who sought to monopolize land, money, or the means of production. If a few people took over most of a country’s money or resources, rising laborers would be forced to work for them forever or, at best, would have to pay exorbitant prices for the land or equipment they needed to become independent.

A lot of water has gone under the bridge since Lincoln’s day, but on this Labor Day weekend, it strikes me that the worldviews of men like Hammond and Lincoln are still fundamental to our society: Should our government protect people of property as they exploit the majority so they can accumulate wealth and move society forward as they wish?

Or should we protect the right of ordinary Americans to build their own lives, making sure that no one can monopolize the country’s money and resources, with the expectation that their efforts will build society from the ground up?

Lee Matz

Letters from an Аmerican is a daily email newsletter written by Heather Cox Richardson, about the history behind today’s politics