This special series by Reggie Jackson explores his journey across four cities in Alabama, to visit historical sites that many are trying to erase from public memory so the disturbing truth about racism, segregation, and White Supremacy can be forgotten. mkeind.com/alabamajourney

Dr. King’s right hand man, the Reverend Ralph Abernathy described Selma, Alabama as the “Capital of the Black Belt.” Back in the 1950s and 60s it was the home of Selma University and Lutheran University which drew some of the youngest and brightest minds from the Black community and became a major intellectual and cultural center. Whites from outside of Alabama had generally never heard of the town.

That would all change on March 7, 1965 when both state and local police brutality attacked 600 peaceful protestors as they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge on their way to Montgomery. The events of that day would become known as Bloody Sunday.

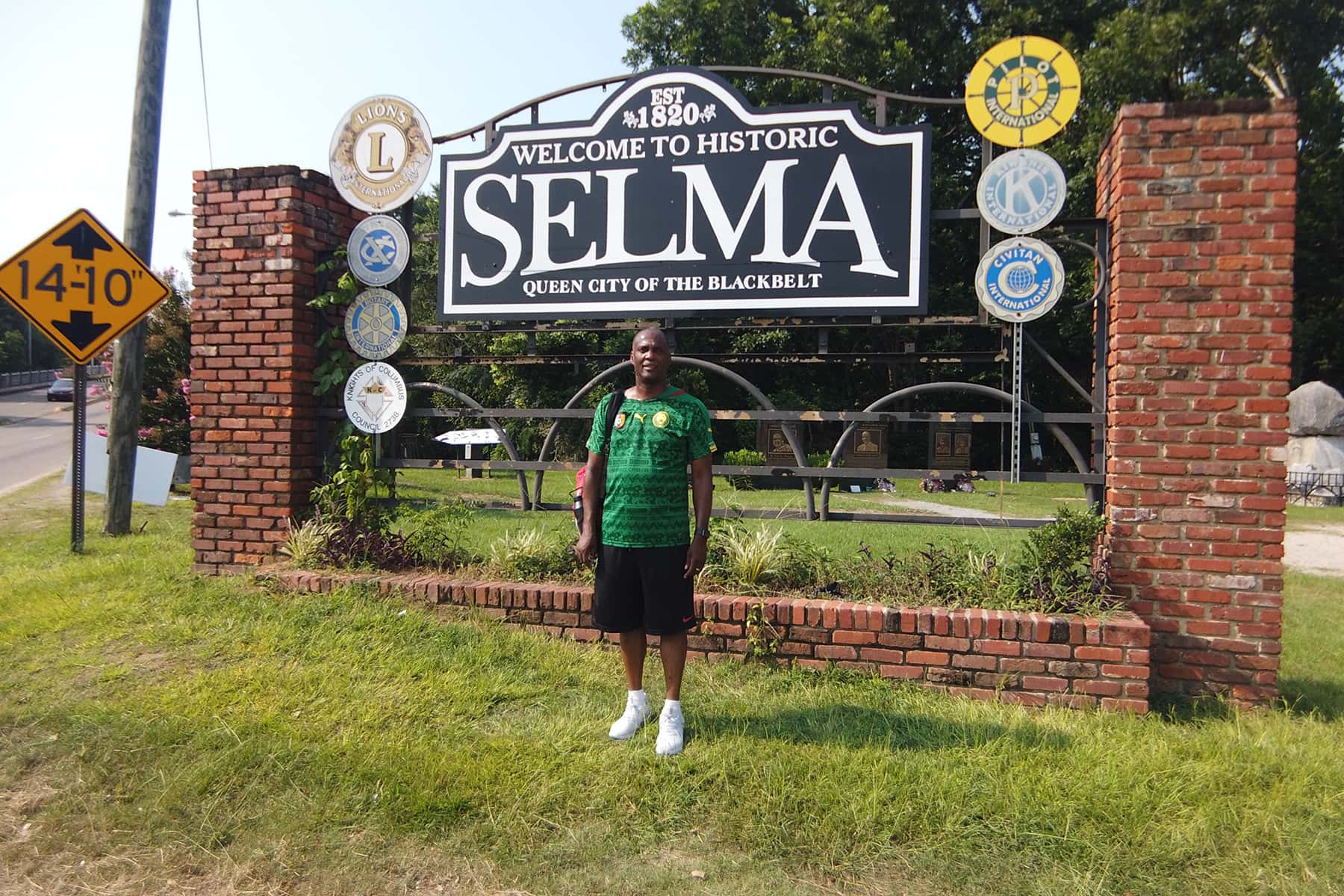

As we drove into Selma from Birmingham we realized that the backroads were the only clear way into town. There were no major highways between the two cities and I expected to see Confederate flags hanging on flagpoles and on the back of cars or trucks as we traversed through the heavily wooded two lane state highways. To my surprise, I saw none. In fact, I did not see a single Confederate flag on our nearly 2,000 mile trip to Alabama and Georgia.

Selma seems like a small, sleepy southern town, much like many others you see traveling in that part of the country. What makes Selma stand out physically is the now infamous Edmund Pettus Bridge. The bridge across the Alabama River is a National Historic Landmark due to the brutal events on Bloody Sunday.

In 1965 none of the Black residents of Selma were allowed to vote. A local organization called the Dallas County Voters League started to agitate for voting rights shortly after the 1964 Civil Rights Bill was passed by Congress. As a result of this, state judge James Hare issued an injunction that forbade public gatherings related voting rights by Blacks in Selma. This injunction was in place for months and led Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and others to target Selma as the next place to demand a change in how Blacks were treated in the Jim Crow south.

A group of activists met at the Gaston Motel in Birmingham in May 1964 and began to work on a plan to deal with the situation in Selma. Amelia Boynton of the Dallas County Voters League came to the meeting to give them details of the struggles by local voter registration activists in Selma. She then asked them to come to Selma to help the Black community secure voting rights and challenge the injunction by Judge Hare. Dr. King had a premonition that he would be killed in Selma prior to them making a commitment to come and support the local pastors who had been in the fight for months.

Blacks were denied the basic right of registering in Selma by authorities who demanded they recite the full Thirteenth or Fourteenth Amendment. They would often ask Blacks, but not Whites, to answer ridiculous questions both written and orally before they would be registered to vote. Not a single White person in Selma was forced to jump through the same hoops as Blacks to register. Illiterate Whites were allowed to register with no problem, but Blacks were denied registration regularly whether they were literate or not.

The local Sheriff, Jim Clark, would become synonymous with racial violence and a strong segregationist approach to the Civil Rights Movement. He was similar to Birmingham’s Bull Connor and both were bullies with quick tempers. Selma’s commissioner of public safety, Wilson Baker was willing to sit down and talk out differences with the Black community, but Clark preferred using violence to settle disputes.

Over the course of several months Dr. King led multiple marches to the courthouse in Selma. He was arrested along with many others who demanded that Judge Hare remove his injunction.

Thirty miles away in Marion, Alabama a group of activist were attacked and Jimmie Lee Jackson was shot by a state trooper as he attempted to shield his mother from being beaten. He died a couple of days later on February 26, 1965, becoming the first SCLC member to be killed during one of their campaigns. Governor George Wallace called SCLC “professional agitators with Communists affiliations” and blamed them for Jackson’s death.

Word went out that the SCLC and Black community would plan a massive march from Selma to Montgomery in response to Jackson’s death and the continuing refusal by state and local officials to sit down and talk.

As the calls went out for volunteers to march down Highway 80 from Marion to Selma and then to Montgomery, Governor George Wallace was intent on making sure that the march ended in Selma. He did not want his office to be blamed for violence because he was planning to run for president in 1968. Wallace set up Sheriff Clark to be the fall guy if anything bad happened.

As my wife and I arrived at our hotel, we realized we were right around the corner from the famous bridge and could actually see it through our hotel room window. It was a hot day, with temperatures nearly 100 degrees and exceptionally high humidity. We decided to walk across the bridge once we got settled into the hotel.

When we first arrived in Selma we drove across the bridge to visit the Voting Rights Museum at the base of the bridge the scene of Bloody Sunday’s carnage. Despite the sign in the window indicating it was open, the door was locked. I was quite disappointed by it being locked but also by the decrepit condition of the building. We would return to this side of the bridge by foot a little later in the day.

As the day arrived for the march, the leaders realized they would probably be stopped before they left Selma. Wallace announced he would use “whatever measures are necessary to prevent a march.”

Dr. King had been receiving nearly daily death threats and many of the leaders asked him to stand down and not participate in the march. As the group was attempting to get President Lyndon Johnson to intervene on their behalf, Dr. King went home to Atlanta, planning to return on Monday March 8. Reverend Hosea Williams was left to make the decision about marching on Sunday. He pushed ahead with plans to cross the bridge to Montgomery. Over 600 would join Williams and John Lewis in walking across the bridge. On the other side they faced dozens of state troopers and local police, some on horseback.

The inevitability of the violence that would occur at that bridge was not surprising. The Edmund Pettus Bridge, built in 1940, was named after a rabid racist who was at one time the Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan. He was considered a Confederate war hero and was seen as one of the leading citizens of Selma. He had served as a general in the Confederate army and was later elected to the U.S. Senate.

Smithsonian Magazine wrote an article about Pettus in 2015. “The bridge was named for him, in part, to memorialize his history, of restraining and imprisoning African-Americans in their quest for freedom after the Civil War,” says University of Alabama history professor John Giggie.” Pettus believed that American civilization could not survive without slavery.

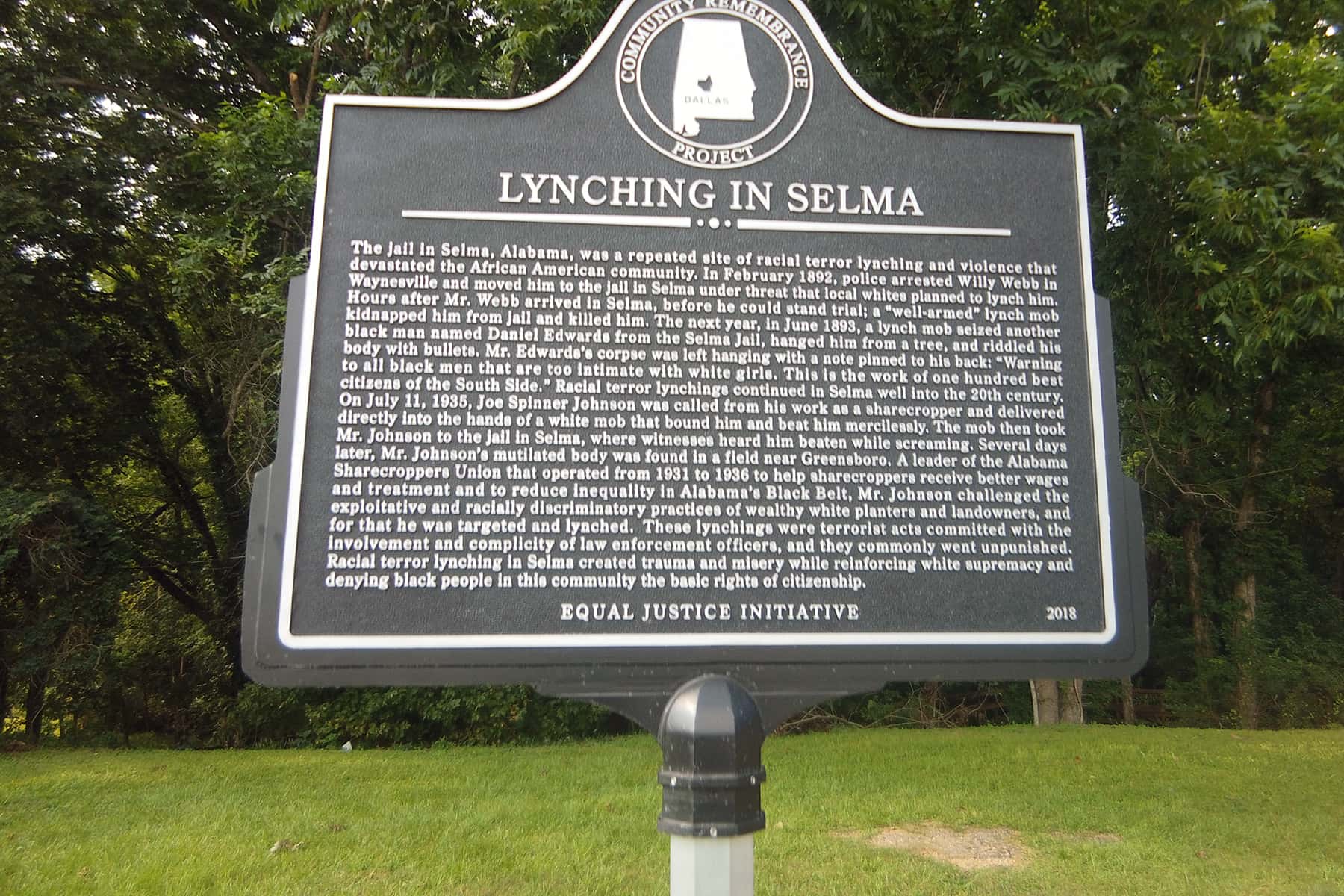

During the war he served as a brigadier general at Lookout Mountain, Tennessee. How ironic that on our way home, we drove the interstate while looking directly at that mountain. Pettus made Selma his home after the war ended. Dallas County, Alabama was the scene of 19 lynchings between 1877 and 1950, according to the Equal Justice Initiative database. Violence against Blacks was nothing new in that place.

As the marchers stood facing the police and state troopers they did not have a clue how brutal the attack would be that day. Neither would the dozens of journalists on hand to document the march.

The state troopers and local police were led by Sheriff Clark and Major John Cloud who ordered the marchers to disperse. With news cameras rolling, the troopers and police began by pushing the marchers back toward the bridge. They trampled dozens including John Lewis. Lewis, a future U.S. Congressman, would be one of the first to hit the ground. A large crowd of white onlookers cheered as the marchers were tear gassed, trampled and beaten with billy clubs.

In the television coverage of the rampage, you can hear bones being broken by the billy clubs used by police indiscriminately. No one was off limits. Lewis suffered a bloody beating and later stated “I don’t see how President Johnson can send troops to Vietnam—I don’t see how he can send troops to the Congo—I don’t see how he can send troops to Africa and can’t send troops to Selma.”

The vicious beatings made national and international news. Dr. King called on clergy from around the country to come and support the campaign in Selma. Over 2,000 marchers soon came to Selma awaiting a court order from federal Judge Frank M. Johnson to continue the march. He said he would issue a restraining order to prohibit a new march until March 11. King led the marchers up to the troopers and then turned back, hoping to not see anyone else beaten. He was severely criticized by many for this decision.

Later that night, local Whites attacked and beat to death Unitarian Minister James Reeb, a White minister who had answered King’s call to come to Selma. He died two days later.

The march would be delayed while the leaders waited on President Johnson to intervene. On March 17, the president submitted legislation on national voting rights protections to Congress. The federally sanctioned and protected March eventually crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge on March 21, two weeks after Bloody Sunday. By the time they arrived in Montgomery on March 25, over 25,000 marchers had participated in the fifty mile walk. Dr. King spoke to the crowd of thousands at the end of the march.

“The end we seek is a society at peace with itself, a society that can live with its conscience. And that will be a day not of the white man, not of the black man. That will be the day of man as man.”

Later that night, Viola Luizzo, a White housewife and Unitarian from Detroit was shot in the face and killed by Klansmen as she drove Black teenager, Leroy Moton back to Selma on Highway 80.

On August 6, President Johnson signed the 1965 Voting Rights Act into law with King by his side.

As I left Selma to begin driving to Montgomery, I knew that the events in Selma just months before I was born, would be impactful on the rest of my life journey. Taking that walk across the bridge, sweating like I was at Packers training camp, left an indelible impression on me. I was walking in the footsteps of some of the most courageous Americans this country has ever known. We are all indebted to their sacrifices and resiliency in the face of massive resistance by people who wanted to keep them “in their place.”

Current battles to teach this history is reminiscent of that time. Despite what some say today, when they argue that teaching this history is divisive, I see as being the same as those segregationists in Alabama in the 1960s. They are attempting to keep us “in our place” in the same way the state troopers, Jim Clark and George Wallace did in 1965. They will not succeed any more than the White community in Selma and Montgomery did. We are too strong to just give in to this racism. We will continue marching on this journey of respect and being treated like human beings.

Next stop is Montgomery, home of the famous Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Equal Justice Initiative’s Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice. I’ll discuss that in tomorrow’s column.

- Reggie Jackson: My journey to visit Birmingham, Alabama and the history some want us all to forget

- Reggie Jackson: My journey to visit Selma, Alabama and the history some want us all to forget

- Reggie Jackson: My journey to visit Montgomery, Alabama and the history some want us all to forget

- Reggie Jackson: My journey to visit Tuskegee, Alabama and the history some want us all to forget

- Reggie Jackson: Final thoughts on my journey to visit Alabama and the history some want us all to forget