EAA AirVenture 2025 marked the 75th anniversary of the Korean War with one of the largest gatherings of Korean War-era aircraft seen in the United States in decades.

The lineup brought together a rare mix of piston-engine icons and early Cold War jets, machines that defined the air war over the Korean peninsula and symbolized the technological shift underway at mid-century.

The featured aircraft included the F4U Corsair, P-51 Mustang, B-29 Superfortress, AD-4 and AD-5W Skyraiders, PB4Y Privateer, Stinson L-5 Sentinel, and Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star, representing the United States and United Nations forces.

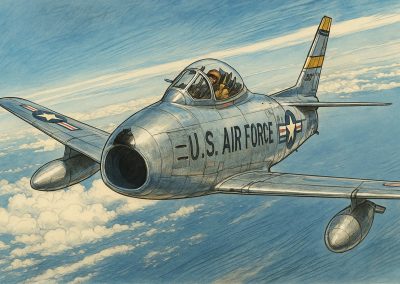

They were joined by Republic F-84 Thunderjets and F-86 Sabres, aircraft central to the transition into jet-powered aerial combat. On the opposing side of the Cold War’s first open conflict, MiG-15 and MiG-17 fighters were present, with Soviet designs flown during the war by both North Korean and Chinese forces, and by Soviet pilots operating illegally.

While the Korean War remains less publicly commemorated than other 20th-century conflicts, the air war it produced had a lasting impact. The conflict marked the first large-scale jet-versus-jet combat in history. It became a proving ground for aircraft that were still in development when the war began.

Dogfights between F-86 Sabres and MiG-15s over “MiG Alley” in northwest Korea helped define Cold War air combat doctrine, leading to rapid evolution in aircraft performance, weapons systems, and pilot training.

The B-29 Superfortress, a four-engine heavy bomber carried over from World War II, played a central role in strategic bombing campaigns during the first year of the Korean War. Early missions focused on industrial targets and transportation infrastructure.

However, its effectiveness declined as enemy jet fighters, especially MiG-15s, challenged the B-29’s previously dominant airspace position. The B-29’s vulnerability to these faster, higher-flying jets helped accelerate the U.S. Air Force’s shift away from piston-engine bombers and toward jet-powered strategic systems.

The appearance of both AD Skyraiders and P-51 Mustangs highlighted the continued use of older, propeller-driven aircraft in ground support and reconnaissance missions well into the jet era. The Skyraider, in particular, gained a reputation for its ruggedness and heavy ordnance load, and remained in use by both the U.S. Navy and Air Force throughout the conflict. Unlike the fast-moving jet fighters, the Skyraider could loiter over the battlefield and deliver precise strikes, often in direct coordination with troops on the ground.

The inclusion of early jets like the P-80 Shooting Star and F-84 Thunderjet also underscored the transitional nature of the Korean War air campaign. These aircraft, some of which entered service just months before the war began, reflected the growing pains of first-generation jet propulsion.

The P-80 was the first U.S. jet fighter to see combat in Korea, though it was quickly outclassed by the arrival of the Soviet MiG-15. The F-84, more capable at high altitudes and longer ranges, took over escort roles and ground-attack missions by 1951.

The Soviet-built MiG-15, with its swept wings, speed, and climb rate, was a shock to American pilots in the early stages of the war. Based on captured German aerodynamic research and powered by a reverse-engineered Rolls-Royce Nene engine, the MiG-15 was the first aircraft fielded by Communist forces that could challenge U.S. air superiority directly.

Its appearance forced the rapid deployment of the F-86 Sabre, which restored a balance in the skies through improved maneuverability and gunlaying radar. The resulting confrontations over the Yalu River and other northern sectors created a new kind of air war—faster, higher, and less forgiving.

Unlike World War II dogfights, where visibility and sustained turning battles defined engagements, the Korean War brought hit-and-run passes at transonic speeds. American and Soviet pilots rarely saw their opponents face-to-face. Many never even saw the aircraft that shot them down.

The inclusion of these aircraft at AirVenture 2025 served as more than a historical display. It was also a bridge to the lived memory of a war that divided a nation and displaced millions. For Korean-American families, the sight of those machines in the air recalled not just the battlefields of the 1950s, but the circumstances that drove immigration and exile, events still shaping Wisconsin communities today.

While the aircraft themselves are mechanical, their presence in commemorative settings like EAA AirVenture speaks to how memory is constructed, especially within diasporic and veteran communities.

For Korean-Americans whose families were displaced by the war, and for American veterans who served during the conflict, these machines represent more than tactical innovation. They are instruments of survival, trauma, and legacy.

The display of MiG-15s, in particular, evoked powerful reactions from the public. These aircraft were both symbols of Soviet-aligned air power and direct threats to U.S. and allied pilots, including those flying B-29 bombing runs over North Korea.

The MiG-15’s ability to climb, dive, and strike with speed marked a turning point in aerial warfare. In archival U.S. Air Force reports, numerous accounts detail the psychological strain of encountering a jet that could appear, strike, and vanish before piston-driven escorts could react.

That vulnerability helped hasten the deployment of the F-86 Sabre in increasing numbers by late 1951. The Sabre quickly became a defining image of U.S. airpower in Korea. Pilots who flew the F-86 achieved an overall kill ratio estimated at between 7:1 and 10:1 against MiG-15s, depending on the source and era of reporting.

The Sabre was equipped with radar-ranging gunsights and powered by a General Electric J47 turbojet engine that provided a high thrust-to-weight ratio for its time. Its design emphasized both speed and agility, crucial in the high-altitude engagements that characterized the latter half of the conflict.

While the Sabre-MiG duels are the most studied aerial encounters of the war, they overshadow the broader and more complex air campaign. Close air support and tactical bombing missions were flown daily using Skyraiders, Mustangs, and other aircraft that had served in World War II.

The Stinson L-5 Sentinel, a light liaison aircraft, was critical for medical evacuations and artillery spotting—tasks that carried enormous risk in forward areas. Such aircraft lacked the speed or altitude to avoid enemy fire, making their missions among the most hazardous.

Also on display at AirVenture was the PB4Y Privateer, a long-range patrol bomber derived from the B-24 Liberator. While it did not play a frontline combat role in Korea as it had in World War II, it served in support capacities, including maritime patrol and weather reconnaissance in the early years of the conflict.

Its presence rounded out a historical picture that often centers only on dogfights and fighter aces, overlooking the slower aircraft that operated under different, often less public, pressures.

The war’s aviation legacy also shaped geopolitical developments. The Korean air campaign was one of the first where intelligence gathering, electronic warfare, and radar jamming began to evolve into specialized missions. Night interception techniques, radar-guided bombing, and the early use of forward air controllers set precedents that carried into later conflicts in Vietnam.

In Milwaukee and other Midwestern cities, the Korean War prompted small but meaningful demographic shifts. Korean War-era immigration policies allowed for some Korean civilians, particularly orphans, adoptees, and war brides, to enter the U.S. in the years following the 1953 armistice.

Wisconsin’s Korean-American population grew in subsequent decades, eventually forming church communities, language schools, and business networks. For members of that diaspora, events like AirVenture created unexpected moments of confrontation and connection, reminders of histories that often remain unspoken in daily life.

AirVenture’s Korean War anniversary display closed not as a reenactment, but as a reminder of a conflict often overlooked, of technology that reshaped warfare, and of lives altered far beyond the battlefield. The aircraft on display embodied not just innovation, but consequence, connecting distant histories to those generations still living with their aftermath.