Japan’s Emperor Akihito will abdicate the Chrysanthemum Throne to his son Crown Prince Naruhito on April 30, 2019, almost three years after he suggested his age and health were affecting his ability to carry out his official duties.

The 85-year-old’s retirement is the first abdication by a Japanese emperor for 200 years, allowing his eldest son to become the 126th occupant of the oldest throne on the following day. Emperor Akihito announced in 2016 that he feared his age and declining health would leave him unable to perform official duties.

Initial plans for the succession to take place at the start of 2019 were scrapped in favor of a date that would enable Akihito to mark his 30th year on the throne. Some officials had originally voiced concern that a New Year abdication would clash with seasonal events and imperial rituals.

Akihito became an enormously popular figure after succeeding his father, Hirohito, Japan’s wartime emperor, in January 1989. While the postwar constitution prohibits Japanese emperors from wielding political influence, Akihito has used his role to promote reconciliation with former victims of Japanese wartime aggression. On a visit to China in 1992, he said he “deeply deplored” an “unfortunate period in which my country inflicted great suffering on the people of China.”

He and Empress Michiko, a commoner whom he met while playing tennis, have also had a prominent role in helping the victims of natural disasters, making several visits to the region devastated by the 2011 tsunami. The name given to his reign – Heisei or “achieving peace” – will be replaced when Naruhito becomes emperor at the age of 59. Akihito and Michiko will move into a new home after they vacate the imperial palace.

Japan’s government rushed to draw up legislation to accommodate Akihito’s wishes because the 1947 imperial household law has no provision for abdications. The last emperor to abdicate was Kokaku in 1817. Akihito’s retirement and the engagement of his eldest grandchild, Princess Mako, reignited the debate about the shortage of male heirs and a possible succession crisis in an imperial line that stretches back 2,600 years.

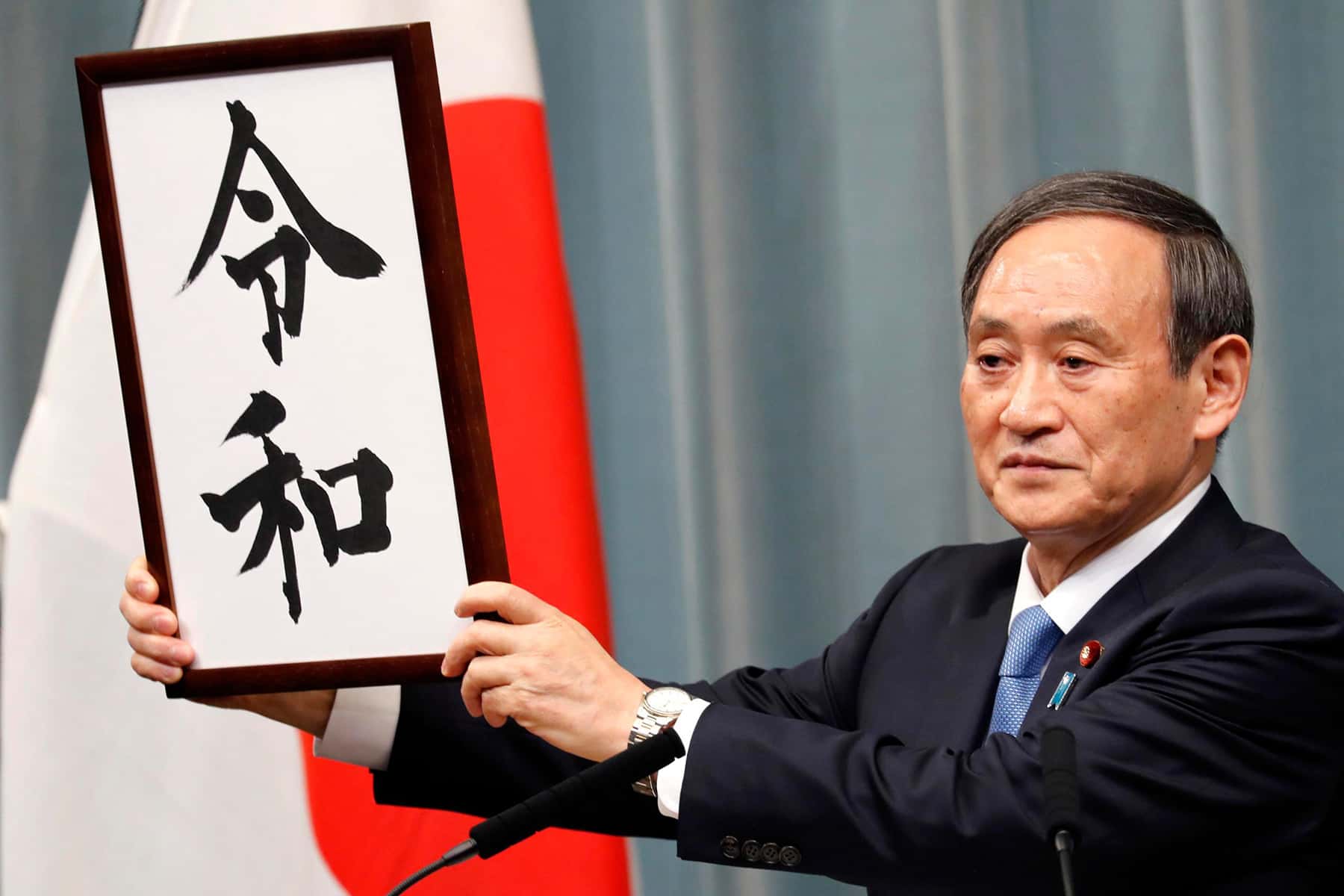

Much of Japan came to a standstill on April 1, during a live broadcast announcement from the prime minister’s official residence in Tokyo. When Crown Prince Naruhito formally accedes to the Chrysanthemum Throne, the event will be marked by a change of era name, from “Heisei” to “Reiwa.” Cabinet chief secretary, Suga Yoshihide said: “The new era is Reiwa” and unveiled a framed calligraphy that presented the two Chinese characters chosen to write the name.

ERA NAMES

Era names have always had huge significance in Japan – and this is the 248th time a new era has been named since the system started in 645AD. Dates in Japan have traditionally been expressed by the year of the imperial era, the gengō or nengō, and the system still dominates official life. It is commonplace still to talk of such-and-such an event of 1979 as being in Shōwa 54, or one of 2001 as being in Heisei 13. Everyone knows when they were born or married according to this system, which exists in parallel to the western calendar.

Before the modern period, era names were not the same as the emperor’s name, and most emperors’ reigns were characterized by more than one era. Names sometimes changed for reasons of good omen – as in the case of the Taika era (645-650) being replaced by the Hakuchi (“white pheasant”) era (650-655) after the emperor was given a rare albino pheasant and judged it to be lucky. More usually, they were changed to purify the reign from a recent calamitous event. For example, the change from Angen to Jishō in 1177 followed the destruction of a quarter of the capital in a huge fire.

But since 1868, the era name has remained unchanged throughout an Emperor’s reign, no matter what happens. Recent emperors have been referred to in Japan solely by their era name after the end of their reign: Emperor Hirohito, as the West knows him – who reigned from December 25 1926 until his death on January 7 1989 – is referred to as the Shōwa emperor in Japan after his era name.

The era name is chosen to embody the hopes of the nation for the new reign, and is constructed from two Chinese characters with Chinese-derived pronunciations. Meiji, which ran from 1868 to 1912, was the “bright” (mei) “rule” (ji) – where the mei carried the connotations of civilization and enlightenment, reflecting Japan at its post-feudal stage of rapid modernization.

Meanwhile Taishō (1912-1926) was the “great rectitude”. Shōwa (1926-1989) expressed the hope for “shining peace” – but the history books can tell us that the first two decades of this era are associated instead with militarism, war and defeat. So perhaps it’s no coincidence that the desire for peace was continued in Heisei (1989-2019), “creating peace”.

WHAT ‘REIWA’ MEANS

As Suga unveiled the new name, which had been selected from a secret shortlist the same morning, a first reaction was naturally: what does it mean? The second character (wa) means “peace”, “peaceful” or “harmonious”. A wish for peace is a common element in era names – as we’ve seen it has recurred in the past two era names. It has also long been used to mean “Japanese” as used in washoku “Japanese food,” and wafū “Japanese style”. So it is a way of indelibly linking the idea of Japan with the idea of peace.

But what about the rei element? This has never been used in an era name and normally carries a range of meanings, including “command”, “law” or “cause to”. It can, however, also mean something more like “auspicious” or “good”. Suga and Japan’s prime minister Shinzō Abe, explained that it was derived from the eighth-century Japanese poetry collection Man’yōshū, which includes a group of 32 traditional Japanese poems on the theme of plum blossom.

The poems’ preamble states: “Being an auspicious (rei) month in early spring, the weather was pleasant and the wind was peaceful (wa)” So, as Abe explained, the name has connotations of spring and renewal – but also contains a wish for a Japan where everyone and their hopes for the future can bloom.

It is significant that the name has come from a Japanese work. Previous names have been couched in Chinese literary tradition – so this marks a significant break. Abe and his conservative support in the ruling Liberal Democratic Party had been calling for a name rooted in Japanese literary heritage.

Shōwa is remembered as an era of war and defeat followed by national and economic rebirth, while Heisei will be associated with Japan’s economic stagnation and demographic crisis. Ultimately, then, the significance of Reiwa will only be understood in light of the events of the new reign.

Nicolas Tranter

Eugene Hoshiko