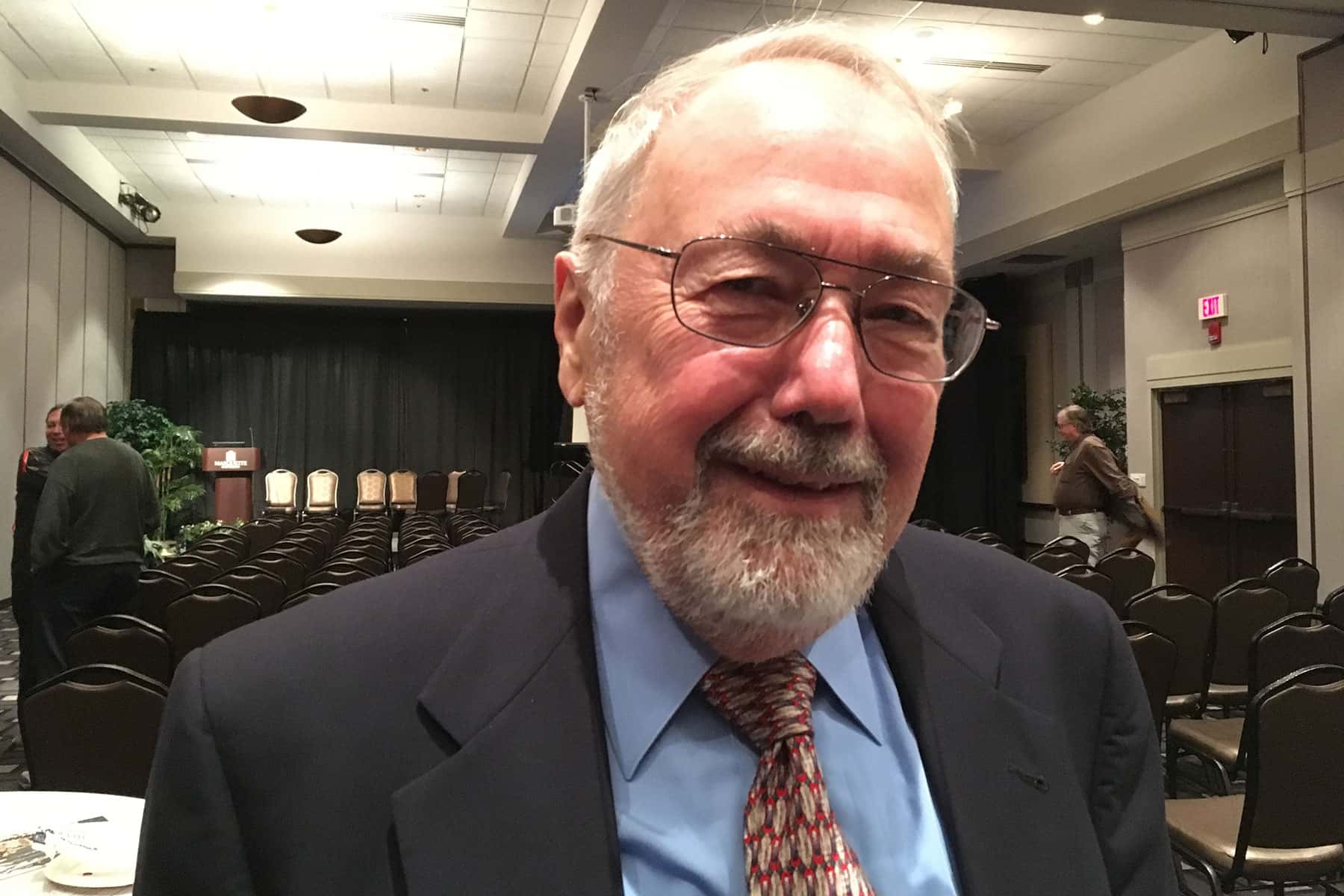

Celebrated Smithsonian historian Herman J. Viola spoke at Marquette University about the overwhelming representation of American Indians in the United States military, past and present.

American Indian veterans have been an essential part of United States military for the past 200 years. The numbers speak for themselves: 12,000 American Indians volunteered to fight in World War I, despite not yet being considered citizens. They also represented about ten percent the population that served in World War II, the American Civil War, Korean war, Vietnam war, and the war in Iraq. Despite their efforts, these veterans and their contributions have been largely unknown by the general American public.

Herman J. Viola, the renowned Smithsonian historian, has been working to bring awareness of American Indian military service over his entire professional career. His book “Warrior in Uniform: The Legacy of American Indian Heroism” exemplifies his passion for telling their stories. His most recent project saw the installation of an American Indian Veterans Memorial in Washington DC, adjacent to the central mall.

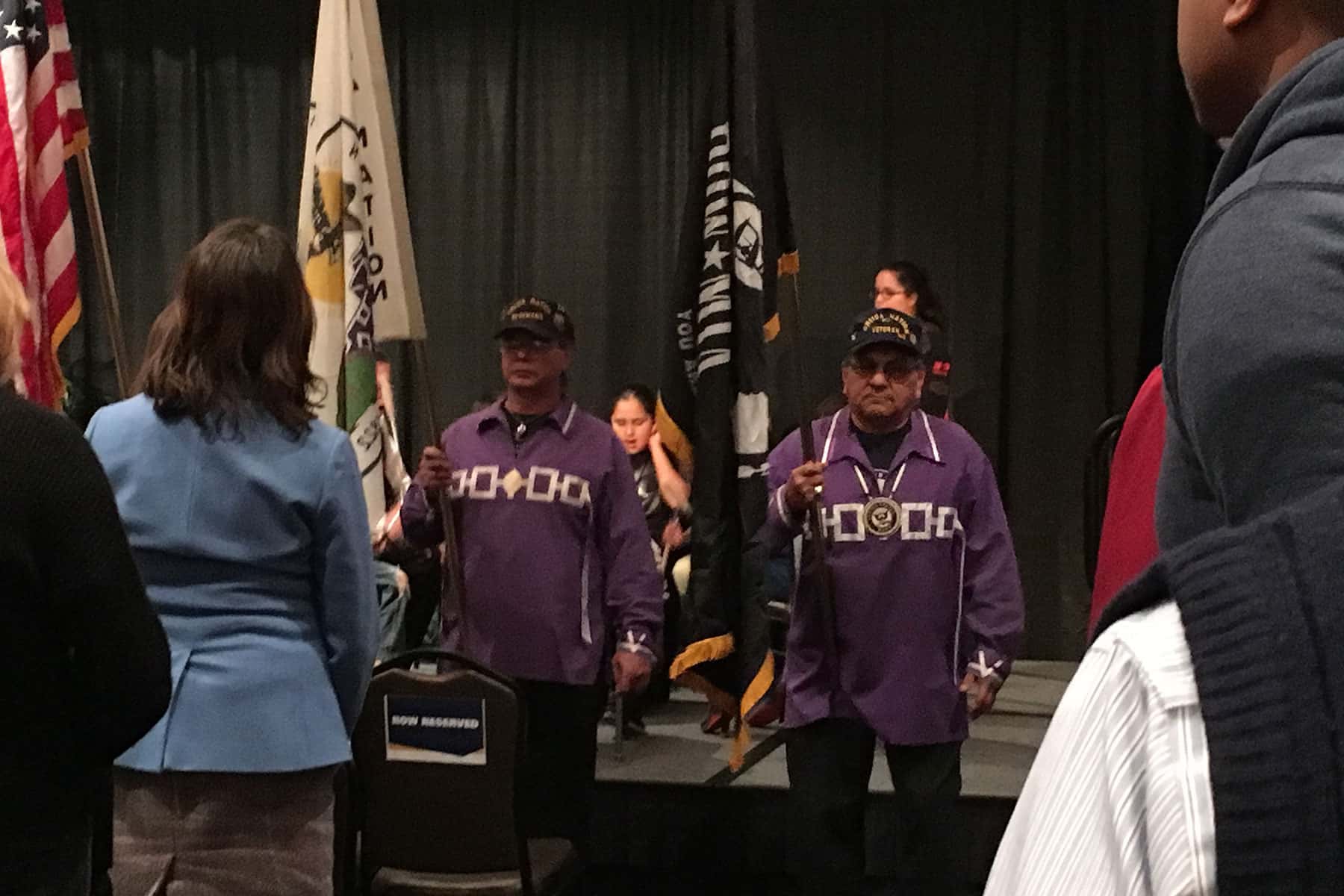

Viola gave a presentation about American Indian veterans entitled “Forgotten Soldiers: American Indians in Armed Forces in the United States” at Marquette University on November 28. Before introducing Viola, a local American Indian school performed an opening ceremony to acknowledge the veterans in attendance, who carried Wisconsin and United States flags as they entered.

Educator Mark Denning, known by his spiritual name of Nadway Benaisé, led the ceremony with a few words in support of the thousands of veterans currently protesting at the Dakota pipeline.

Though Benaisé is not a veteran himself, he works to help returning veterans manage post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). An overwhelming number of veterans, including American Indian veterans, return with PTSD. Ira Hayes, one of the six flag raisers immortalized in the iconic photograph of the flag raising on Iwo Jima during World War II, suffered from this combat condition.

According to Viola, Hayes was a Pima American Indian and Marine. After being featured in the famous Iwo Jima picture, Hayes returned to the United States as a figurehead for the war efforts. He had a difficult time coping with the fact that he was relaxing and enjoying entertainment while his fellow soldiers were being kіIIed. His untreated PTSD led him to suffer from chronic alcoholism, and ultimately to his dеаth.

After 35 years of interviewing American Indian veteran, Viola had many personal stories to tell about the soldiers he has met. Benaisé appreciated Viola’s ability to bring these stories of so many forgotten soldiers.

“I was so happy that he addressed the name and origin of every soldier whose photo he presented,” said Benaisé. “These veterans are not just photos and dog tags. They are people who did heroic things.”

Viola’s presentation about American Indian military efforts proceeded chronologically, starting with their participation in the Civil War. He proceed to discuss their efforts in World War I, which took a surprising turn. Military leaders learned that the language of the American Indians was an excellent way to keep information from German intelligence. From this discovery, the famous code-talkers were born.

“This is no exaggeration, but the first time they used the code-talkers to send messages was the turning point of World War I,” said Viola. “It ended just months later.”

During World War II, the United States military enacted a formal program to train code-talkers, who played an essential part of military intelligence and communications. American Indians also served in the Korean War. Viola painted a picture of how the American Indian population was proud of their soldiers in that conflict.

“A veteran’s mother couldn’t speak English, but she was so proud of her boy serving in the military,” said Viola. “Whenever a plane flew over she would go outside and sing an honor song.”

Viola also told the story of Sergeant John Raymond Rice, a Ho Chunk American Indian who served in Korea and received a bronze star after being killed. When his body was returned home, his local church refused to bury his body, as the cemetery was “just for whites.” Military officials were outraged and had Rice buried in Arlington National cemetery with full military honors.

American Indians continue to serve in the military today in large numbers. Viola’s work memorialize their efforts strives to bring light to these current and past soldiers who defended America’s freedom.

It is especially important to bring light to these patriots in an educational setting, like Marquette University, as many students have never been exposed to American Indian history. Also, as Belaisé described, Marquette has not always been a welcoming place for American Indian students.

“I went to school at Marquette for four years, and while I was here I was the Marquette Warrior for the basketball team,” said Belaisé. “We thought we could change how the country views native people, but there were personal costs for that. I couldn’t quite move forward with my education at Marquette because I didn’t feel welcome. I didn’t feel there was a place for me here.”

Though Marquette has since changed their Warrior Mascot to a Golden Eagle, the university still has work to do to fully make American Indian students feel welcome. Presentations like Viola’s will help educate the public on the importance of making the stories of American Indians, and particularly those of veterans, heard.

As a veteran once told Viola, “Finally, someone in the United States is recognizing what we Indians have done.”