In honor of Black History Month, the Wisconsin Housing and Economic Development Authority (WHEDA) held a leadership reception for ACRE alumni on February 19 at the Sherman Phoenix.

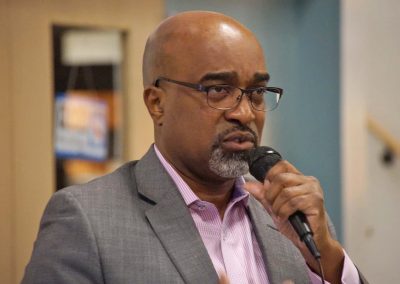

Joaquin Altoro, current Chief Executive Officer of WHEDA, hosted a historic conversation with Antonio Riley and Wyman Winston, former WHEDA executive directors, about the condition of current real estate opportunities and emerging developers. While WHEDA has been focused on addressing the home ownership needs of Wisconsin’s underserved communities, it has also assisted efforts to grow the pool of emerging developers.

One avenue has been through the Associates in Commercial Real Estate (ACRE) Program. The industry-supported initiative recruits and retains people of color for careers in commercial real estate. It is administered through LISC Milwaukee in partnership with Marquette University, the Milwaukee School of Engineering, and the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. The 26-week program includes instruction from industry professionals, site visits, and hands-on development experience.

Born on the south side of Milwaukee with a Puerto Rican and Mexican heritage, Altoro talked about his first access to the African American community during middle school when he was bused to the north side.

“Something that I realized very quickly was, one of the greatest gifts given to Wisconsin is black Milwaukee,” said Altoro. “That is a fact we need to acknowledge, and why I wanted to have this event. It is an opportunity to have the practitioners of real estate and emerging developers of real estate come together in a conversation.”

Altoro said he wanted to use the event as a platform to provide information, exposure, and support for getting anyone engaged in real estate development. He led the conversation on that subject along with Riley and Winston, marking the first time the three had done so together in public.

“When I got to WHEDA, I was the first African American leader at the agency, and there were some folks who were a little bit concerned about a black guy running things,” said Riley. “But at that time, WHEDA had less than 1% of minority participation in the programs of a $3 billion agency. So we had the audacity to create what we called the emerging business program.”

That program consisted of three components. It had to make sure that whenever WHEDA financed a tax credit deal in certain zip codes, it had a minimum of 25% minority participation. There was an employment component, and the flagship effort was the co-developer program. At the time, all the people of color who were working in the tax credit field were doing it as not-for-profit. The goal was to teach those individuals how to do the developments for profit.

Kalan Haywood and Melissa Nicole Allen were two examples of people who benefited from the program. Not because it gave them a handout, but because it provided an opportunity for them to realize their vision. In doing so, it helped build assets and wealth in the Milwaukee community.

“In 1989, Milwaukee ranked Number One in the denial rate of African American borrowers versus white borrowers. That meant for every white borrower who was denied a mortgage, five African Americans were denied,” said Winston. “The number was astounding, and it was one of the numerous embarrassments to the state.”

Then Governor Tommy Thompson asked Winston to be a part of a task force that held hearings on the issue. What became clear was that part of the decline in minority neighborhoods and entrepreneurship was directly related to the inability to own a home.

“The reason that Milwaukee ranked at the bottom for minority business startups and business growth was due to homeownership being the gateway. Without homeownership, it was very difficult to make that leap. So we took a look and found HUD and WHEDA had records that were worse than even the bankers,” said Winston. “Those institutions, that had the express purpose to serve that vulnerable population, had denial rates that were just as bad as the commercial industry.”

In Milwaukee it was cheaper to own than it was to rent. Winston remembered what a 67 year-old African American citizens said to the committee in 1989.

I’ve lived in this city all my life. I paid my bills. I’ve never been able to buy a house. But my bank allowed me to buy a new car every two years.

The disparity meant that African American consumers specifically and minority consumers, in generally, were losing millions of dollars that went to pay for housing that was unaffordable. The most important result of the 1989 effort was that WHEDA took a really hard look at itself and changed how it did underwriting.

Lee Matz

Our mission of transformative journalism means that we are editorially independent. Our staff determines what is important news to report on, and in what voice to speak on issues. No one influences our opinion, and no one edits our editors. We are free from commercial bias and are not influenced by corporate interests, political affiliations, or a public preferences that rewards clicks with revenue.

Your Support Matters – Donate Now

As an influential publication that provides Milwaukee with quality journalism, we depend on public support to fulfill our purpose. Our award-winning photojournalism, columns, interviews, and features have helped to achieve a range of positive social impact that enriches our community. Please join our effort by entrusting us with your contribution.