On November 19, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln delivered one of the best known speeches in American history, at the dedication of the Soldiers National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

This essay is part of a series of opinion pieces. Each one is no longer than 272 words, the length of Gettysburg Address, and responds with a view of how Lincoln’s spoken ideas in Gettysburg are relevant to America in 2017.

Our 90-year-old guide at Gettysburg National Military Park, whose Grandfather fought for the Union on the very fields we walked, asked if I wanted to stand where President Lincoln had spoken. We linked arms and proceeded up the hill to sacred ground. It was cold and raining, the same as in 1863 when showers unveiled those recently buried in shallow graves. Lincoln’s serious, inspirational, and carefully chosen words moved me as then as they have since my first visit to Springfield on a 5th grade field trip.

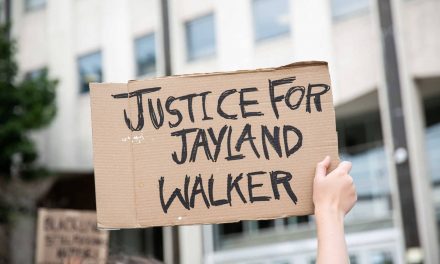

Lincoln asked us to never forget what those who fought did, and to dedicate ourselves to the great task ahead, which I interpret as a universal human equality. My young son now carries his own memory of this magnificent historical figure as an example of great triumphs attainable even if it takes longer than expected to find our way. My public radio audience carries memories of countless hours devoted to Lincoln’s moral leadership. He is worth all the attention.

Our tour guide has since left this earth, and I am getting old. But as long as I am here, those mystic chords of memory will remain alive. Unlike the current president who offers cruel and thoughtless words, Lincoln, considered one of the finest writers of the 19th century, gives us poetry and genius.

In saying goodbye to Springfield, Lincoln expressed confident hope “that all will yet be well.” My hope is nourished by his memory and our dedication to unfinished work. May we once again be governed by an individual whose qualities include great intellect, generosity, devotion to duty, and empathy.

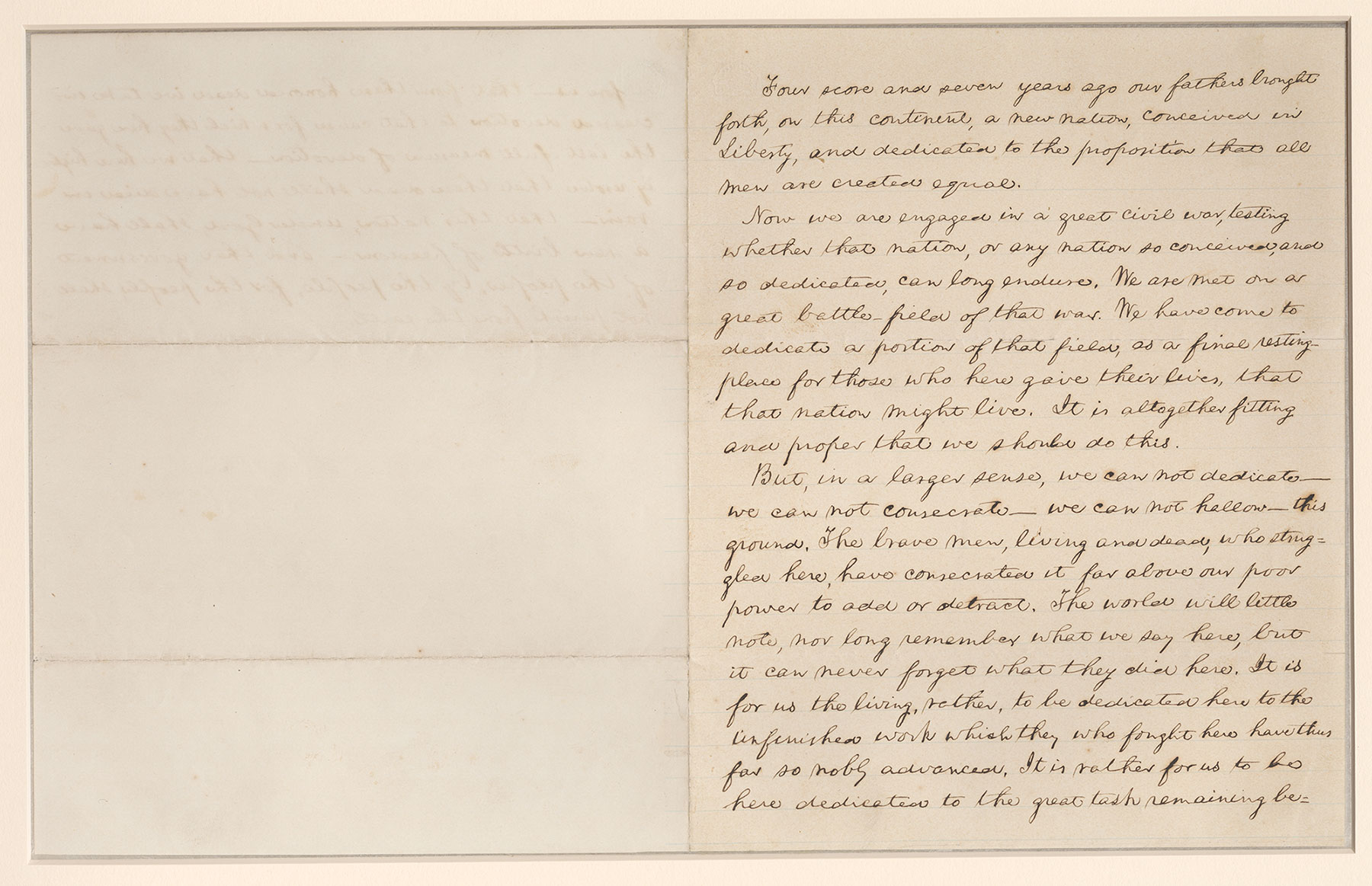

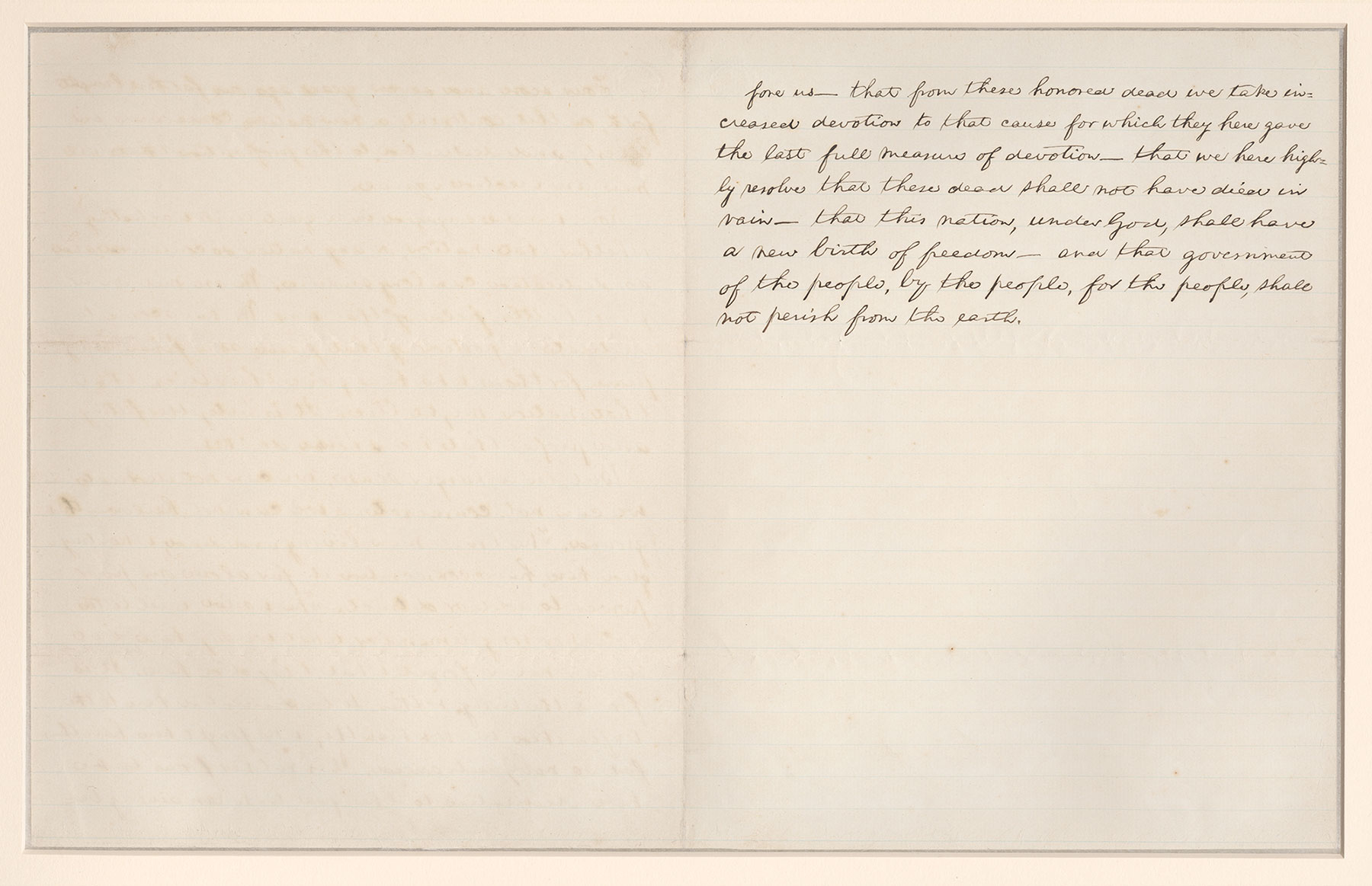

Lincoln's Gettysburg Address (The Bancroft Version)

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives, that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate, we can not hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they here gave the last full measure of devotion – that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Cornell University Library’s copy of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address is one of five known copies in Lincoln’s hand. Written out by President Lincoln at the request of U.S. historian, George Bancroft, this copy, the fourth that Lincoln composed, is known as the Bancroft Copy.

Kathleen Dunn is a retired and former host on Wisconsin Public Radio for nearly a quarter-century

Andrew Aliferis and Mort Künstler