Last year, Milwaukee Independent was in production on what would become the award-winning news series Milwaukee Voices. Korean Experiences. Even though 72 features were published, with more than 20 interviews, several ideas were cut or went undeveloped due to deadlines. With 2025 being a significant anniversary year for the Korean War, this article is one of those untold stories.

While working at the Milwaukee Business Journal in January of 2024, I came across a situation that did not fit inside the newsroom’s normal lanes of coverage.

An elderly man had taken his own life in an assisted living apartment somewhere near downtown. There was no note, no obituary, and no family who came forward. He left behind only one item: a cardboard box filled with personal effects.

The building’s engineer, who was married to the pastor of my church at the time, found the box while helping clean out the apartment. He told me that without anyone to claim it, everything would have been thrown away.

So he took it home instead, to keep stored at the church parsonage. He did not have the heart to see the last things a veteran left behind be discarded. I was never shown the box, but I was given access to some of the contents inside, which included a scrapbook of black-and-white photographs and news clippings, and a handful of medals.

I did not have my camera with me, so I snapped some images for reference with my iPhone. I did not know what I would do with the images, but I found the objects fascinating, and the situation of the forgotten veteran to be sad.

I have very little recollection of the event after ten years. I think I skipped taking photos of some things, and other images had already been removed from the scrapbook. I wish I had more methodically documented the materials, but I had no idea what I would ever do with them.

It was possible the veteran’s name was written somewhere in the scrapbook. Maybe the pastor’s husband knew it, but I did not ask. After the pastor and family moved away in 2015 to lead a new church, whatever access I had to that material disappeared. What I am left with after all these years are the pieces I saved, and a mystery that I never wrote about.

From my research, two Korean War veterans died in Milwaukee in January 2014, but both were well-known. Patrick F. Bolger, on January 20, was a tavern owner and youth coach. And Raymond J. Baranowski, on January 29, was a yacht club member and U.S. Marine.

The medals were standard-issue campaign decorations: the American Campaign Medal, the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, the Korean Service Medal, and the United Nations Korea Medal.

Combined, they traced a path from Milwaukee to World War II through the Korean War. This was someone who had served in multiple theaters. He had likely been in Europe first before 1945, then Korea, and had remained in the Army well into the early 1950s.

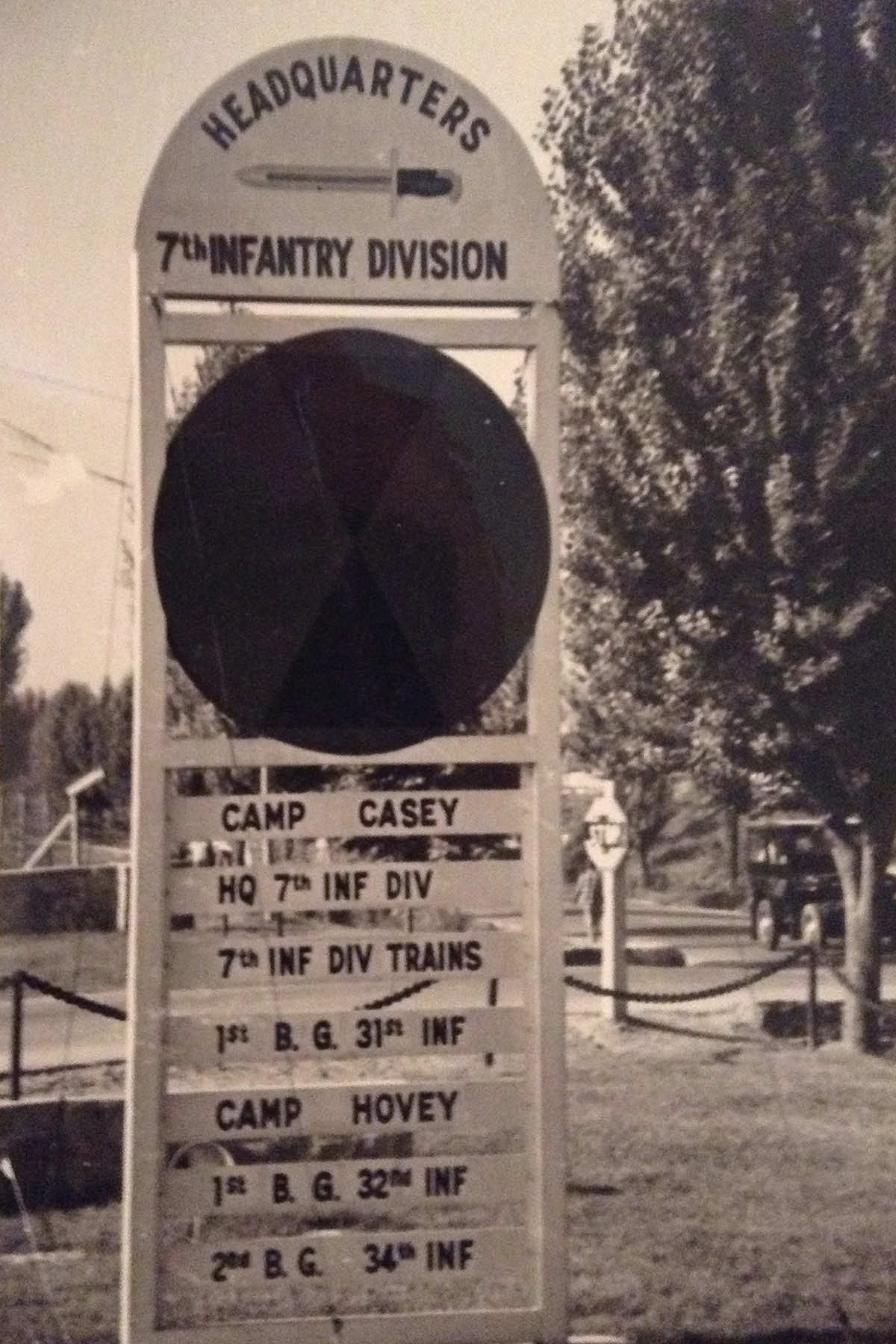

The photo trail offered some clues about his unit affiliation. A clean shot of the Camp Casey signboard placed him inside the 7th Infantry Division, likely at division headquarters. Camp Hovey, also listed, further narrowed his location within the command structure.

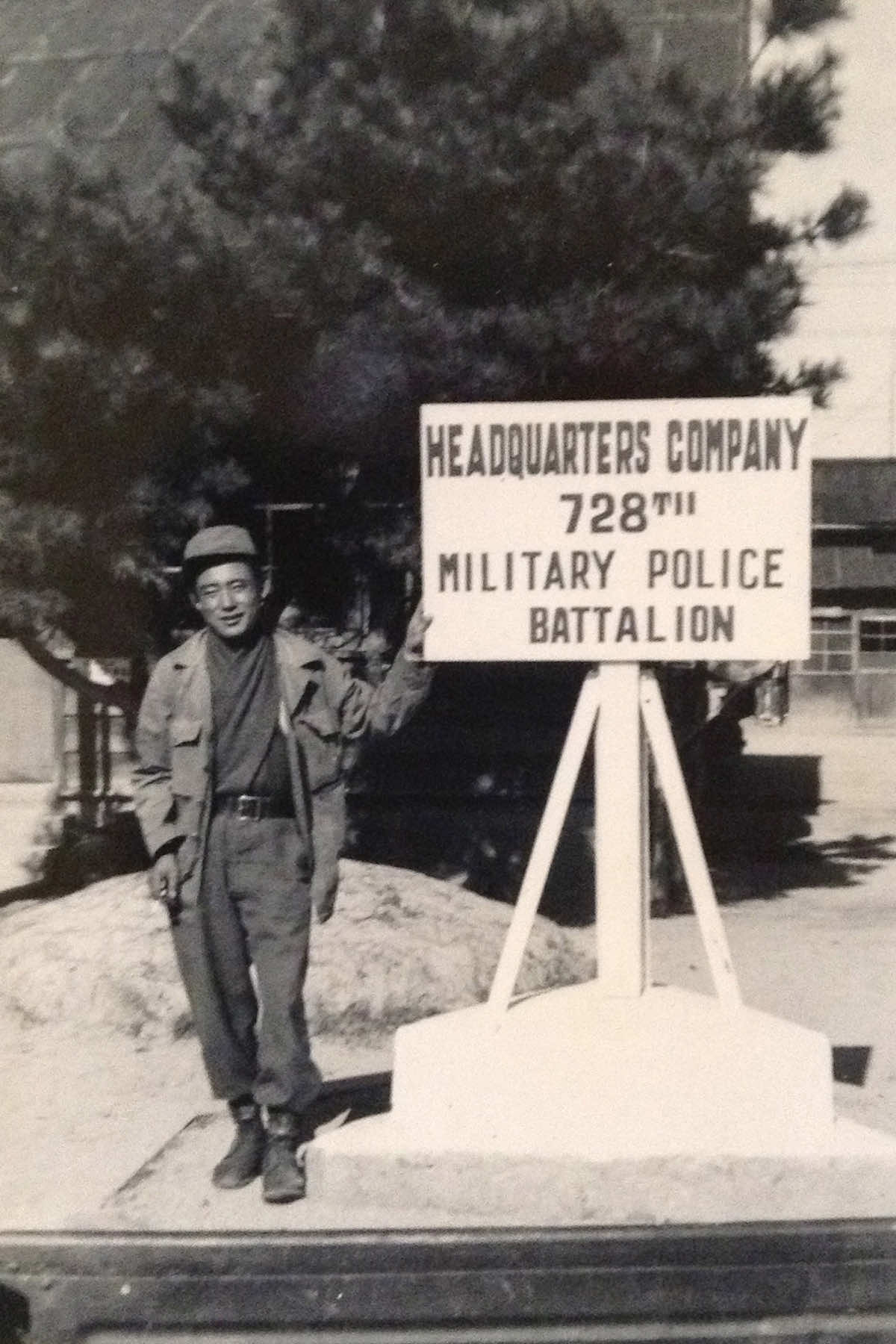

Another snapshot, of a uniformed Asian soldier standing next to a wooden placard labeled “Headquarters Company, 728th Military Police Battalion,” indicates he was likely assigned or worked alongside the military police. Most probably in an engineering role.

The 728th was historically based in Yokohama, Japan. The 13th Engineer Combat Battalion served with the 7th Infantry Division in Korea, and his collar pin appears to resemble the Engineer Castle insignia.

Had he actually been an MP, seeing that symbolism in a photo would be expected. But taken together, these images suggest he served in a supporting role with the military policeman attached to 7th Infantry, stationed at Camp Casey near the Korean DMZ.

That would explain his presence at political protests, both in Korea and later in Japan, where MPs were routinely tasked with monitoring demonstrations, photographing unrest, and gathering crowd intelligence. Engineers would also be on call to assist with clean-up, repair, or restoration of order if protests turned violent or damaged local infrastructure.

His March 1952 stop at the Yuraku Officers Club in Tokyo likely marked a formal R&R break before returning to his post in South Korea. In that photo, where the veteran identified himself as the third person, he is seen wearing a U.S. Army uniform.

Another image captured what appeared to be a Korean public meeting, with a note identifying it as a protest against army conscription. The caption read: “A meeting of Koreans to protest the drafting of men for the army. Oct. ’51.”

This aligns with documented unrest in South Korea at the time, when military drafts were expanded under U.S.-backed efforts to build up the Republic of Korea’s armed forces. That a foreign soldier would be present, or at least close enough to photograph the scene, suggested access beyond routine patrol or transport.

More personal moments emerged in a few other frames. One showed a White man, likely the veteran, seated with a Korean woman wearing a Western-style dress. He is holding a baby in one arm and a pipe in the other. The photo is not posed like a studio shot, but neither is it accidental. The quiet scene appears private.

The connection between them is not clear. Whether this was his family, someone else’s, or a snapshot of a brief relationship cannot be determined. But the moment, like many in the collection, was preserved deliberately.

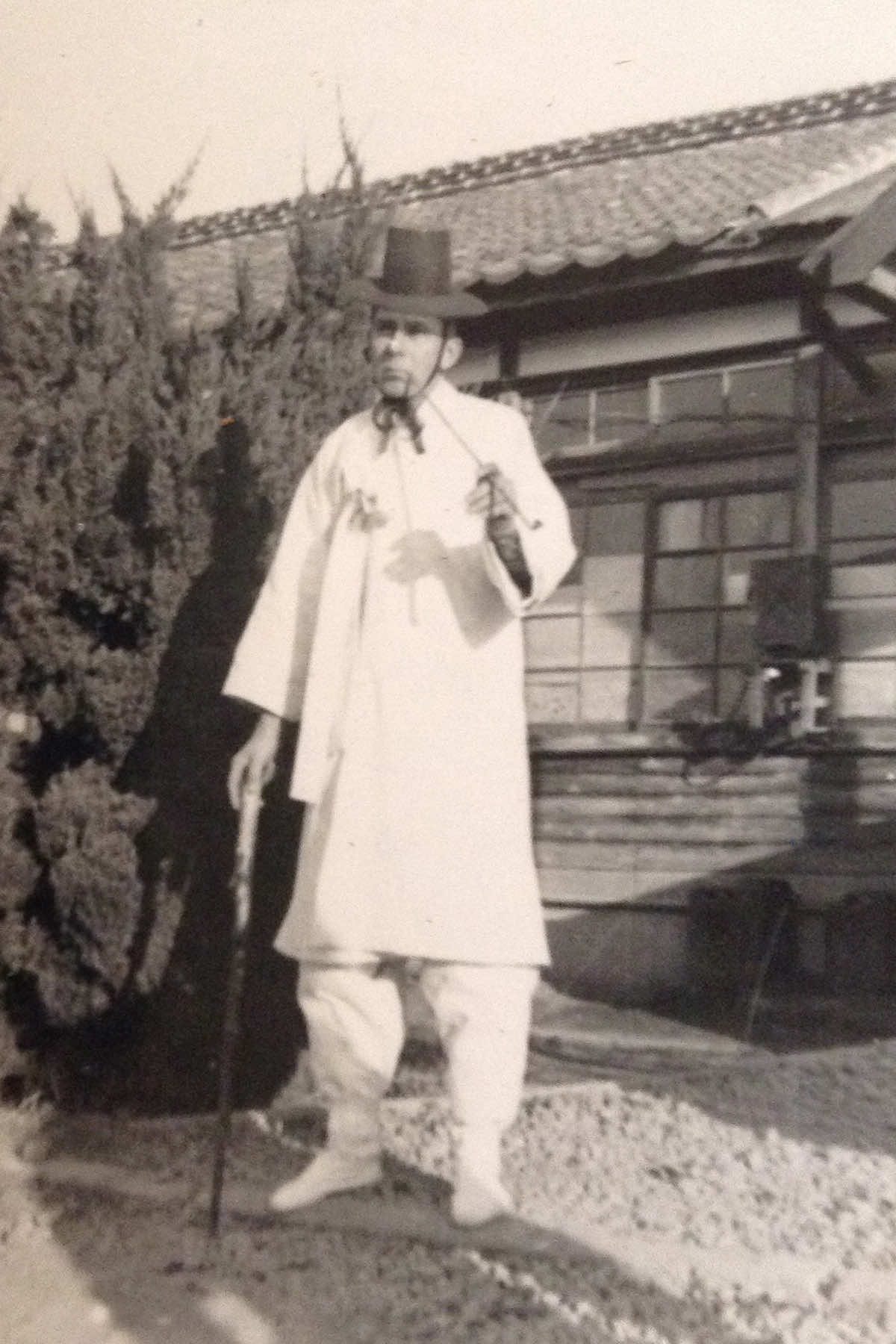

In another image, the same man is dressed in traditional Korean male attire, including a black horsehair “gat,” the cylindrical hat historically worn during the Joseon dynasty. He stands outside a building with traditional roof tiles and wooden paneling, likely somewhere near his base in South Korea.

There is no caption or context to explain why he wore it. Whether the moment came from a ceremony, a cultural exchange, or a personal invitation is not known. But the tone of the photo is composed and unforced, not performative.

Compared with later images, particularly those taken in Japan, his face and build are leaner in 1951. If the sequence of the scrapbook is any guide, this was earlier in his tour, before he rotated out of Korea for a post in Japan.

One artifact in the scrapbook stood apart, a front page of The Nippon Times from May 2, 1952. The lead headline read:

BLOODSHED, RIOTS MARK MAY DAY IN TOKYO AS COMMUNIST-LED HORDES BATTLE POLICE IN VIOLENT ANTIFOREIGN DEMONSTRATIONS.

A subhead underneath reported: 10,000 Nippon, Korea Reds Battle Police, Damage Property. The article described May Day violence in Tokyo, including physical clashes and damaged storefronts, as demonstrators fought with Japanese riot police.

The inclusion of the newspaper clipping, along with actual photographs used in the article of demonstrators clashing with Japanese police, suggests that the man had been reassigned to Japan and was a first-hand witness to the events.

It is unknown how he obtained the famous photos, several of which remain uncredited to this day, but having them implies he worked with or may have known who took the pictures. Paired with his probable MP assignment, this strengthens the case that he served in a documentation role, possibly assisting military press units. The scrapbook’s mix of prints and press coverage points to someone operating with direct access to sensitive events.

I never saw the scrapbook again. It is possible that the box contained more objects, like letters, names, or documents that could have offered more insight into the life and identity of the veteran. Whatever might have filled in the blanks is now gone.

What remains are these fragments: medals earned across two wars, photos that moved between combat zones and quiet quarters, and the outline of a veteran whose path passed through Europe, Japan, Korea, and back to Milwaukee.

Not every war story ends with a gravesite, a family, or a folded flag. Some are lost in closets, reclaimed only by accident. In this case, the man’s story, whoever he was, tells of someone who witnessed protests against forced conscription, stood amid anti-American riots in Tokyo, and documented formal and informal life among Koreans and Americans alike.

The war in Korea is described as “forgotten,” a label imposed more by America’s discomfort than any lack of violence or sacrifice. If that Korean War veteran had no one close to remember him at his end a decade ago, I do not expect that anyone who reads this article will be able to make a connection to his identity.

But I still feel it is important to publish his photos and what little I know, to be a witness and leave a public record in the absence of anything else.

© Photo

Lee Matz and Nippon Times