America’s most well-known photographer, Ansel Adams, documented the Manzanar War Relocation Center in California and the Japanese Americans interned there during World War II in 1943.

The Library of Congress made digital scans of both the original negatives and the photographic prints created by Adams. They appeared side-by-side for the first time, allowing viewers to see Adams’s darkroom technique, and in particular how he cropped his prints.

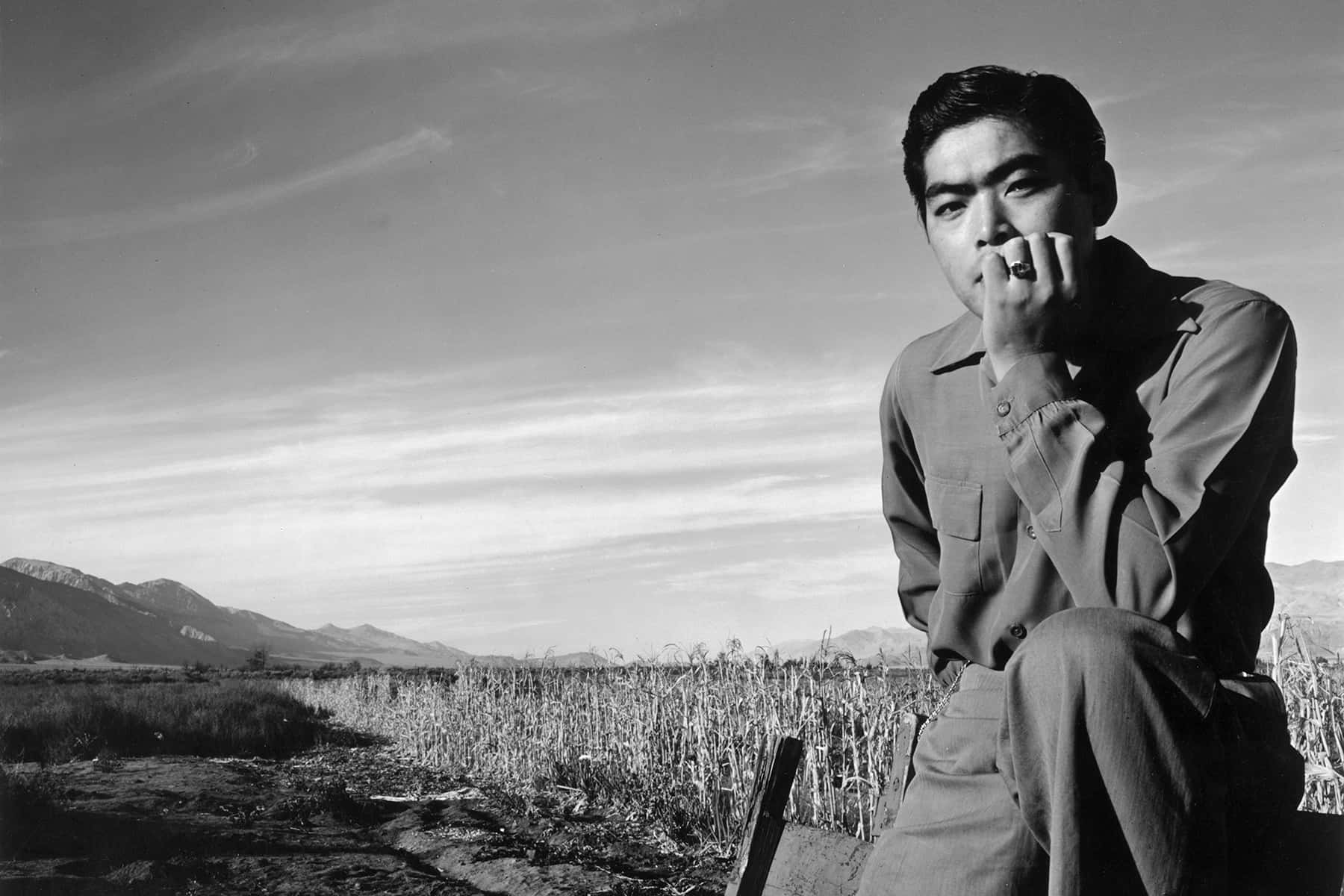

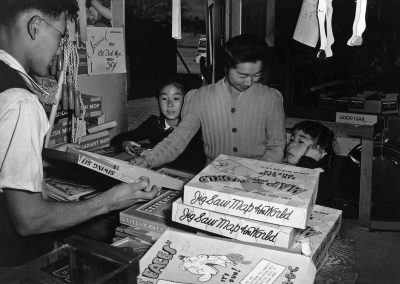

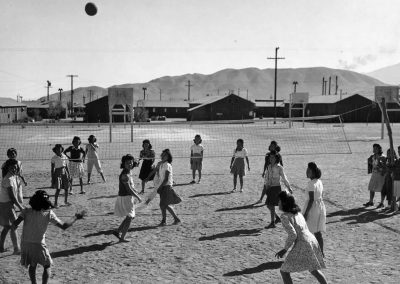

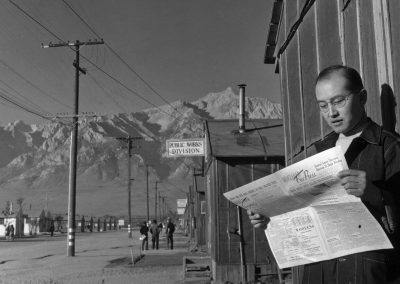

Adams’s Manzanar work is a departure from his signature style landscape photography. Although a majority of the more than 200 photographs in the collection are portraits, the images also include views of daily life, agricultural scenes, and sports and leisure activities.

When offering the collection to the Library of Congress in 1965, Adams said in a letter:

“The purpose of my work was to show how these people, suffering under a great injustice, and loss of property, businesses and professions, had overcome the sense of defeat and despair by building for themselves a vital community in an arid (but magnificent) environment … All in all, I think this Manzanar Collection is an important historical document, and I trust it can be put to good use.”

Also included in the digital library is the first edition of Born Free and Equal, Adams’s publication based on his work at Manzanar.

Best remembered for his views of Yosemite and the Sierra Nevada, Adams photographs emphasize the natural beauty of the land. By contrast, Adams’s photographs of people have been largely overlooked. Trained as a musician, in 1927 Adams made a photograph “Monolith, the Face of Half-Dome” that changed his career. By 1940 he was an established fine art photographer.

After Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, fear of a Japanese invasion and subversive acts by Japanese Americans prompted President Franklin D. Roosevelt to sign Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. The act designated the West Coast as a military zone from which “any or all persons may be excluded.”

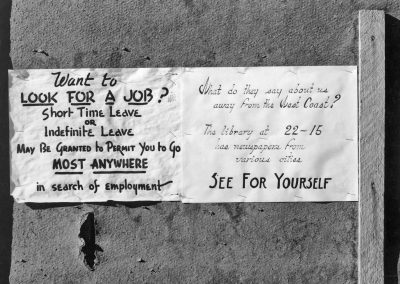

Although not specified in the order, Japanese Americans were singled out for evacuation. More than 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry were removed from their homes in California, southern Arizona, and western Washington and Oregon and sent to ten relocation camps. Those forcibly removed from their homes, businesses, and possessions included Japanese immigrants legally forbidden from becoming citizens (Issei), the American-born (Nisei), and children of the American-born (Sansei).

The event struck a personal chord with Adams when Harry Oye, his parents’ longtime employee who was an Issei in poor health, was summarily picked up by authorities and sent to a hospital halfway across the country in Missouri.

Angered by that event, Adams welcomed an opportunity in 1943 to photograph Japanese American internees at the Manzanar War Relocation Center, then run by his friend and fellow Sierra Club member, Ralph Merritt.

Adams had already completed a number of assignments for the military as a civilian, including teaching photography at Fort Ord and photographing Yosemite’s Ahwahnee Hotel, which was used as a Navy hospital during the war. But he was anxious for a more meaningful project related to the war effort. Adams’s documentation of Manzanar would become his most significant war-related project.

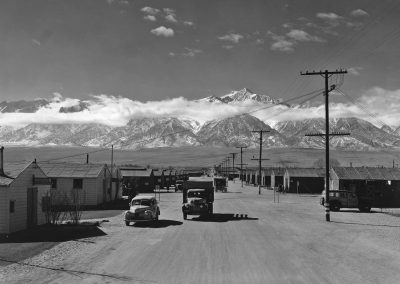

During the fall of 1943, Adams photographed at the Manzanar War Relocation Center, which was located in Inyo County, California, at the eastern edge of the Sierra Nevada mountains approximately 200 miles northeast of Los Angeles.

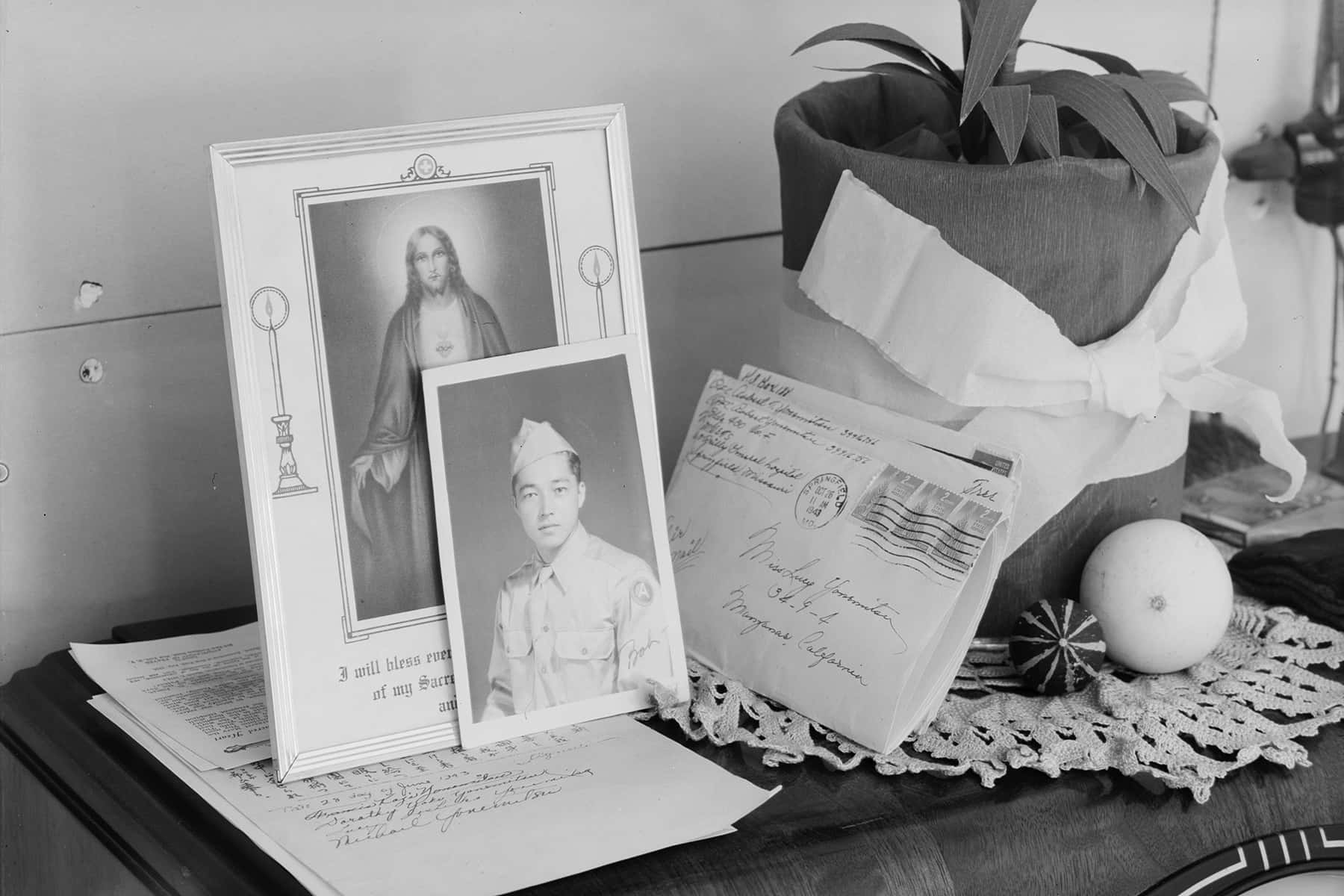

Adams produced an essay on the Japanese Americans interned in the beautiful but remote region, where the mountains served as both a metaphorical fortress and an inspiration for the internees. Concentrating on the internees and their activities, Adams photographed family life in the barracks, internees as welders, farmers, and garment makers, and their various recreational activities.

In 1944, a selection of these images along with text by Adams was published in a 112-page book, “Born Free and Equal.” In a letter to his friend Nancy Newhall, the wife of Beaumont Newhall, curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, Adams wrote:

“Through the pictures the reader will be introduced to perhaps twenty individuals … loyal American citizens who are anxious to get back into the stream of life and contribute to our victory.”

Adams was not the only photographer to work at Manzanar. One of the internees, Toyo Miyatake, had worked as a Los Angeles portrait photographer before he was moved to Manzanar. Although the internees were not allowed to have cameras, Miyatake fashioned one from parts he brought with him in his luggage. Both Adams’s and Miyatake’s photographs present a positive view of the Japanese Americans interned at Manzanar.

In contrast, Dorothea Lange, who had earned her reputation as a social documentary photographer with images of migrant farm workers made during the Depression, worked for the War Relocation Authority photographing the evacuation of Japanese Americans and their arrival at Manzanar. Lange’s vision is uniquely unlike Adams and Miyatake. She photographed the upheaval of the evacuation and the bleak conditions of the internment camps.

In 1988, apologizing on behalf of the nation for the “grave injustice” done to persons of Japanese ancestry, Congress implemented the Civil Liberties Act. Congress declared that the internments were “motivated largely by racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership,” and authorized a $20,000 payment to Japanese Americans who suffered injustices during World War II.

© Photo

Ansel Adams / Library of Congress