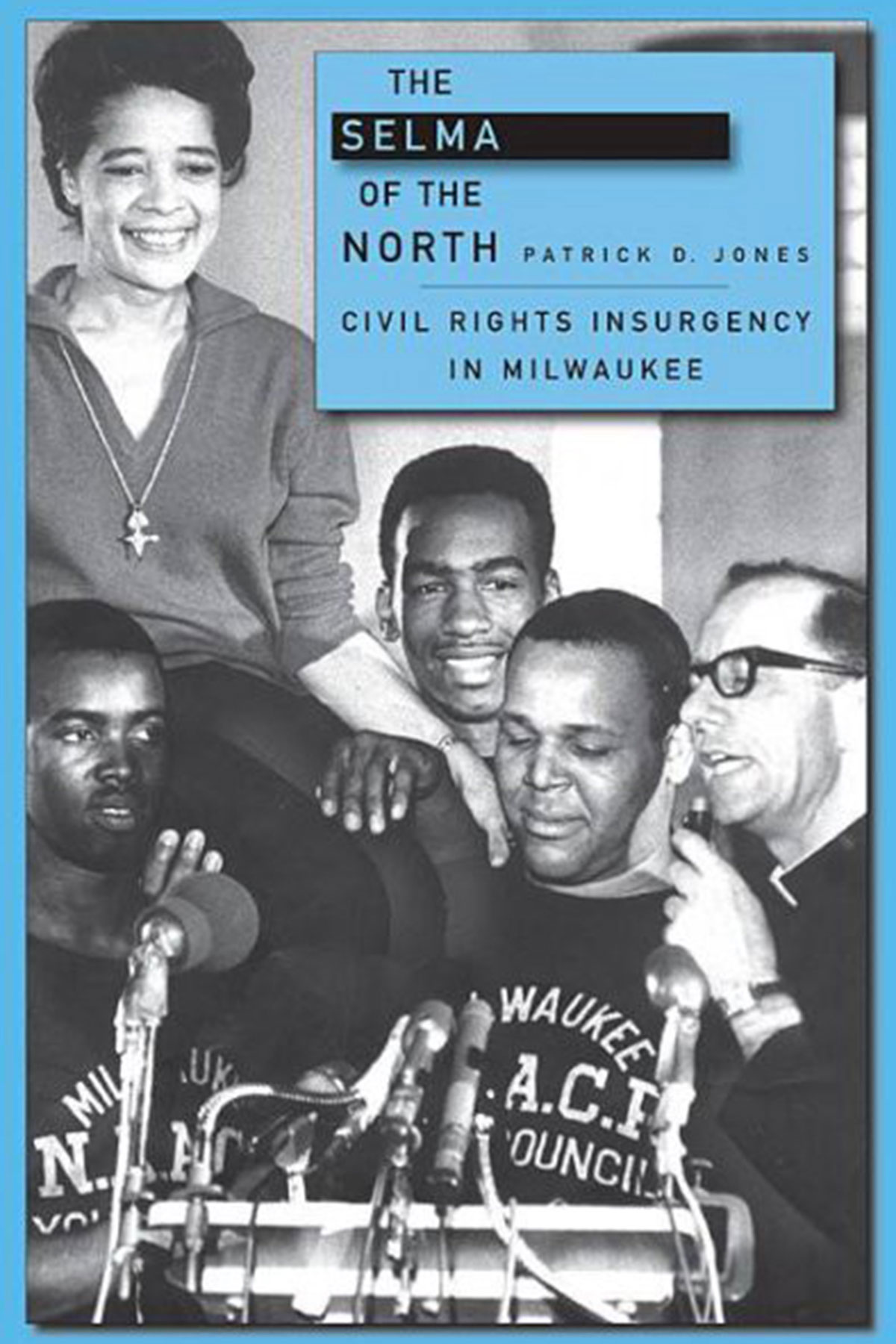

Montgomery. Birmingham. Selma. Each of these American cities is hallowed ground in the modern black freedom movement. But, how about Milwaukee?

Yes, Milwaukee. The Cream City deserves its place in our national narrative of the civil rights era, too.

In a similar way that Birmingham helped spur passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Selma played a catalytic role in the enactment of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, Milwaukee contributed to the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which is celebrating its 50th anniversary on April 11, 2018. The anniversary affords an opportunity to reclaim this critical, but largely over-looked, episode in the struggle for racial justice and reflect on its enduring meaning.

A History of Housing Discrimination

Discriminatory, segregated housing has long been a central feature of America’s racialized urban landscape, particularly important to the northern version of Jim Crow that grew up in the early and mid-20th century as thousands of African Americans took flight from the South, seeking new opportunities and a better life in what they hoped would be the “Promised Land” of the urban North.

Yet, instead, whites used their institutional and extra-legal powers to erect an alternative system of white supremacy and racial exclusion built upon employment discrimination and systematic impoverishment; educational inequality; ghettoization; social segregation; and, limited political and civic inclusion.

A mix of private and public actions, including racially restrictive housing covenants, red-lining, block-busting, steering and a host of other discriminatory practices by real estate and financial institutions, supported and emboldened by governmental policy, radically limited African Americans’ access to the housing market, relegating the vast majority of black and brown people to increasingly overcrowded and dilapidated central city neighborhoods. The very same public policies that created and subsidized affluent, lily-white suburban communities in the post-WWII era (and the attendant accumulation of personal wealth that came with them) also entrenched urban ghettoization (and the systematic disinvestment in communities of color) and fostered a slide into slumification by the late-1950s and 1960s. And, of course, when public policy and institutional actions were insufficient to maintain the color line, white residents took matters into their own hands, employing bullying, intimidation, threats and violence to keep non-whites corralled. When all else failed, they simply moved away from black neighbors.

Within these segregated and racialized urban communities of color, an exploitative and predatory housing market thrived. Most private property was owned by whites and rented out at inflated costs to increasingly desperate black and brown residents. White property owners converted formerly single family homes into apartment units to maximize profits. Basic maintenance and upkeep of these rental properties was neglected, while safety and health codes went largely unenforced. At the same time, government officials increasingly placed public housing projects inside these same inner-city neighborhoods, further concentrating racialized poverty in what came to be called “vertical ghettos.” Over time, large numbers of white Americans began to associate black people with the degraded living conditions they were forced to inhabit, as if it were an inherent trait of blackness, rather than the result of unjust policies and behaviors.

Housing as Contested Terrain in the Civil Rights Era

In the post-WWII era, as a national movement for racial equality emerged in both the American South and urban North, housing became an increasingly critical and contested terrain for civil rights activists, as well as a focal point for white reaction. Many white residents supported African American home-owning rights as long as black people remained a significant urban minority limited to their own distinct neighborhoods. But, as black populations in the urban North grew during the Great Migration, large numbers of white residents came to view the expanding African American presence as a threat. Some did not believe that black people had earned the New Deal entitlements to housing in the same way that whites had. Others associated African Americans with declining property values. Still more thought black rights came at the expense of white rights and that public policy seemed increasingly at odds with white working-class interests.

As the northern struggle for racial justice accelerated during the mid-1960s, open housing emerged as the most divisive and often violent civil rights issue in the urban North. A 1961 report by the National Commission on Race and Housing summarized the problem: “There are probably not fewer than twenty-seven million Americans, or nearly one-sixth of the national population, whose opportunities to live in neighborhoods of their choice are in some degree restricted because of their race, color or ethnic attachments.” The upsurge in popular agitation pushed housing onto the national civil rights agenda.

By 1965, President Johnson became convinced that the problem of racial discrimination in housing was so invidious and pervasive that legislation was required to root it out. He sought to capitalize on his hard-won successes in the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act, as well as the growing urban unrest, to push a federal open housing law as the centerpiece of the 1966 Civil Rights Act, but legislators, backed by powerful housing and real estate lobbies, defeated the measure. A disappointed Martin Luther King, Jr., stated that the demise of the legislation “surely heralded darker days for this social era of discontent.”

The failure of federal legislators to come up with a strong open housing bill spurred a series of local campaigns for fair housing in the urban North between 1966 and 1968. A number of these efforts resulted in significant racial conflict. In addition, the failure of federal legislation and the devolution of the issue to states and localities pit city against suburb, local government against state government. A federal measure would have had the virtue of setting a national standard to which all states and localities had to adhere, thus eliminating the fractured conflicts that erupted between the different layers of government.

By 1967, the open housing movement had built momentum nationally and locally. The failure of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1966 brought out simmering racial divisions within the Democratic Party. The widespread urban violence of 1967, much of which had grown out of the general squalor of segregated urban black communities, put the issue of open housing in a different context, prompting legislators and activists to again push for a law. “One of the burning frustrations Negro residents carry with them in city ghettos,” explained NAACP President, Roy Wilkins, was “the knowledge that even if they want to and have the means to do so, very often they cannot get out.” The Kerner Commission, which released its report on civil disturbances in March of 1968, indicted housing discrimination as a major reason behind African American frustration, racial strife, and urban violence.

Open housing activists in dozens of northern cities took to the streets during the mid-1960s to pressure state legislators and city councils to pass “fair housing” laws. The most visible of these campaigns took place in Chicago. There, in 1965 and 1966, a contentious and fragmented coalition of local civil rights organizations and Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference — known as the Chicago Freedom Movement — led a series of open housing marches through several white working-class neighborhoods. To many, the demonstrations symbolized King’s attempt to prove that his brand of confrontational nonviolent direct action could work in the urban North.

The campaign attracted national media attention when thousands of angry white counter-demonstrators pelted nonviolent activists with a hail of bottles, rocks, cherry bombs and racist epithets. Afterward, King, who was hit in the face by a brick, told reporters, “I’ve been in many demonstrations all across the South, but I can say that I have never seen — even in Mississippi and Alabama — mobs as hostile and as hate-filled as I’ve seen here in Chicago.” The Chicago Freedom Movement degenerated into internal bickering among local and national civil rights leaders, resulting in a hasty retreat from the city by King and the SCLC after they negotiated a severely compromised agreement with city officials. Some saw the failure of the Chicago open housing campaign as a repudiation of King and the SCLC’s nonviolent strategy in the North.

The rising tides of Black Power and urban rebellion, an increasingly unpopular war in Vietnam, a host of blossoming new movements and the beginnings of white backlash all complicated the calculus for the black freedom movement in the urban North. The year after the Chicago Freedom Movement dissolved, further up the shores of Lake Michigan in Milwaukee, many felt that the interracial, nonviolent and church-based movement made its “last stand” with more promising results.

The Fight for Fair Housing in the “Selma of the North”

The pattern of segregation and racial inequality that plagued most large, northern cities in the mid-twentieth century, was particularly stark in Milwaukee. A major industrial site in the U.S. “arsenal of democracy,” Milwaukee attracted thousands of African American migrants, swelling the black population from 2% of the total in 1945 to roughly 15% by 1970. The dramatic rise in black population intensified segregation and sharpened racial tensions. By 1965, residential segregation in Milwaukee was nearly total, with ninety-eight percent of African Americans living in the central city, the largest concentration in the nation.

Even within the boundaries of segregation, significant barriers to homeownership meant that a mere three percent of Milwaukee’s black population owned their own homes in 1960, the lowest rate of black home-ownership in the country. Urban renewal and highway construction projects took large new chunks out of the African American community, further exacerbating the housing crisis by displacing hundreds of residents. The urban crisis that had been developing for decades now accelerated blight and decay. With high unemployment and poverty rates on top of poor housing conditions, social problems in Milwaukee’s black inner-city neighborhoods mushroomed.

By the early 1960s, Milwaukee civil rights advocates had already begun to push housing onto the public agenda. The state NAACP drafted model open housing legislation and organized a fourteen-day sit-in at the capitol in Madison, while liberal and civil rights groups publicized housing discrimination, circulated “Good Neighbor Pledges” to Milwaukee homeowners, and flooded newspapers with personal ads supporting fair housing. Most significantly, Vel Phillips, a middle-class lawyer and the sole African American on the Milwaukee Common Council, introduced a strong citywide open housing ordinance four times between 1962 and 1967, but each time it was voted down by her white colleagues 18–1.

The unanimous opposition to Alderwoman Phillips’s ordinance suggests the formal obstacles facing open housing advocates in Milwaukee. Indeed, as civil rights activists intensified their organizing, so too did white reaction increase. A string of new property owner associations popped up to “defend property rights” against “forced housing.” Hundreds of local white Milwaukeeans signed “stop forced housing legislation” cards and sent them to politicians. In 1963, the Milwaukee Board of Realtors endorsed the National Association of Real Estate Boards’ “Property Owners Bill of Rights,” which warned that open housing legislation would “erode freedom,” “destroy” free enterprise and end American individualism. A statewide open housing bill passed by the legislature in 1965 with the backing of real estate interests excluded almost all housing in Milwaukee’s segregated inner- city neighborhoods.

Nonetheless, local civil rights activists continued their efforts to end housing discrimination. Between 1960 and 1966, a series of civil rights campaigns over employment discrimination, segregated public schools, the membership of local officials in a racially exclusive club, and police brutality had mobilized hundreds of local people, brought a new generation of Milwaukee leaders to the forefront, drawn a modicum of national attention, and crystallized the racial crisis in the city. A white Catholic priest, Father James Groppi, and the local NAACP Youth Council, cut their activist teeth and joined forces during these earlier campaigns, but now drove the local movement in more militant directions.

Experience had taught civil rights activists in Milwaukee that local whites, including political and civic leaders, would not budge from the status quo on race without being compelled to do so. Father Groppi, who had heeded Dr. King’s ecumenical call to Selma in 1965, brought back the lessons he learned about militant nonviolence and the need to foster “creative tension” within the community, flush out racial discrimination, and force people to choose sides and act. The racial stalemate in Milwaukee over housing offered an opportunity to apply these lessons in a northern, urban context.

The Youth Council first got involved with open housing shortly before Christmas in 1966, when a young black Vietnam veteran, Ronald Britton, stopped by their Freedom House and shared the story of his recent encounter with a white property owner along the fringe of the segregated black community who refused to rent to him and his family out of fear that their presence might frighten off white tenants.

In the spring of 1967, Father Groppi approached Vel Phillips and the two decided to work together to mount an escalating direct action campaign aimed at forcing passage of the long-stalled open housing ordinance. Throughout the early summer, Youth Council members picketed outside the homes of six North Side aldermen who had opposed Phillips’ ordinance despite representing large numbers of African Americans. These initial protests garnered little media attention and generated even less public debate.

Then, on July 30, racial violence broke out in Milwaukee’s segregated black community following the latest in a string of late-night clashes between police and young black residents. Eight days later, the toll included four people dead, more than 1,500 arrested, and hundreds of thousands of dollars in property damage. The “riot” dramatically changed the political and social context for local open housing advocates.

Suddenly, Milwaukee’s segregated black community had forced its way into the public consciousness in a frightening new way. Father Groppi and Youth Council leaders sought to capitalize on this sudden attention by escalating their open housing campaign and marching into the white ethnic working-class South Side, a move they understood would likely elicit a strong white reaction. “We didn’t march to the South Side because we wanted to buy a home,” said Prentice McKinney. “We marched there because we needed the media to air it out to the people”

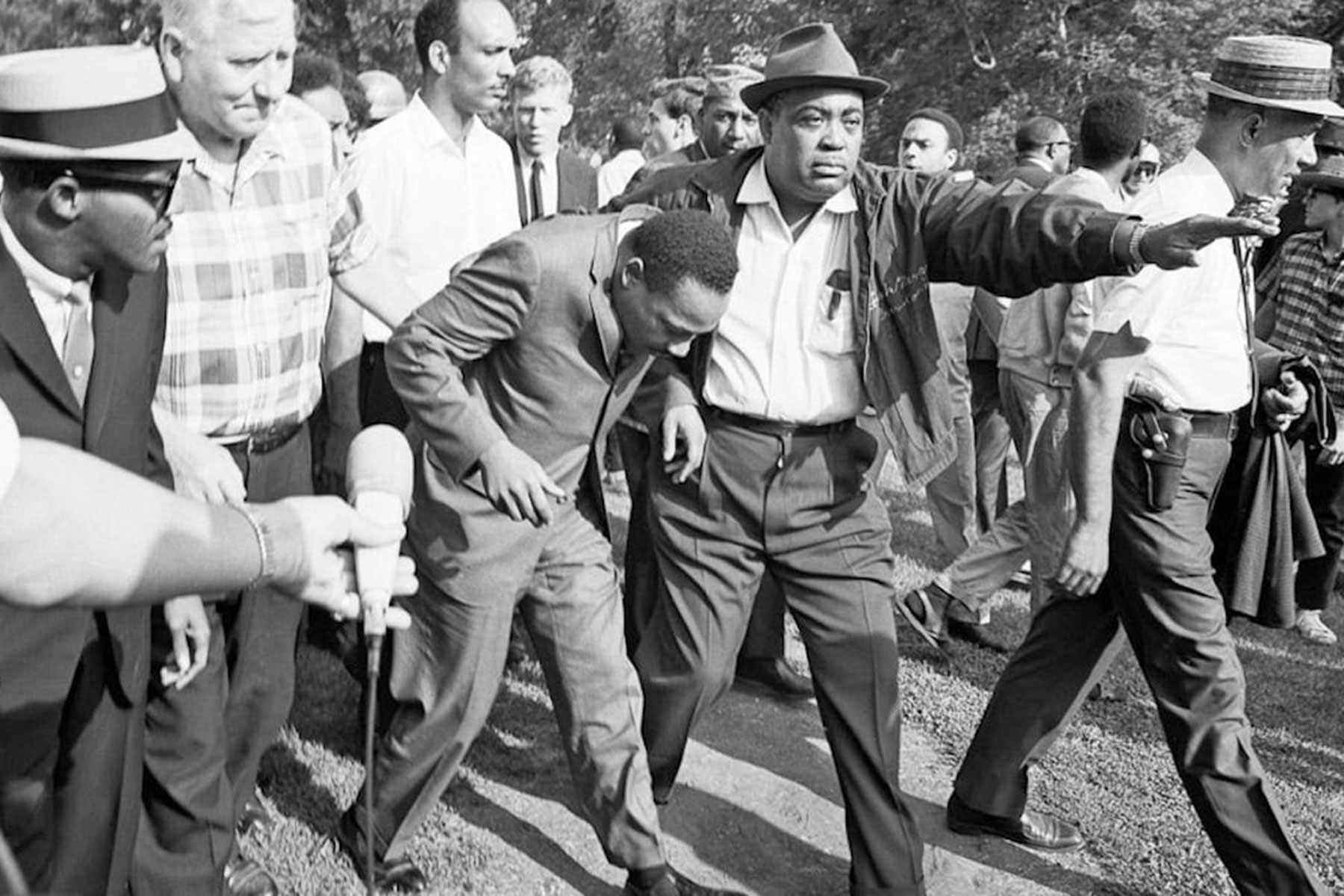

On Monday, August 28, 1967, one hundred open housing advocates gathered for a rally at St. Boniface Church, the spiritual and political home of Father Groppi and the NAACP Youth Council. The group then set off across the Sixteenth Street Viaduct, “the longest bridge in the world,” as the local joke went. It connected “Africa with Poland,” — the segregated African American North Side with the predominately white ethnic working-class South Side. The marchers held a permit to conduct a rally at Kosciuszko Park, not far from the meeting hall where throngs of enthusiastic whites had greeted segregationist George Wallace during the 1964 Democratic presidential primary. There, the YC members intended to introduce a “Declaration of Open Housing,” unofficially claiming into law what the city’s Common Council refused.

The initial half-mile walk across the viaduct was uneventful, but as they approached the other side, they heard the rising growl of more than three thousand white residents who had come out to observe and oppose the demonstration. Many were curious, but some held signs that read, “Polish Power” and “A Good Groppi is a Dead Groppi.” Others yelled, “Niggers go home!” and “Go back to Africa!” Flying stones, bottles, garbage, and chunks of wood accompanied the chants and signs. At the park, an estimated five thousand angry whites closed in on the demonstrators, resulting in scuffling. The violence injured twenty-two, and police arrested nine. Afterward, Father Groppi, who had grown up on the South Side, promised that civil rights activists would not only return the following day, but would continue to march until the Common Council enacted an open housing measure.

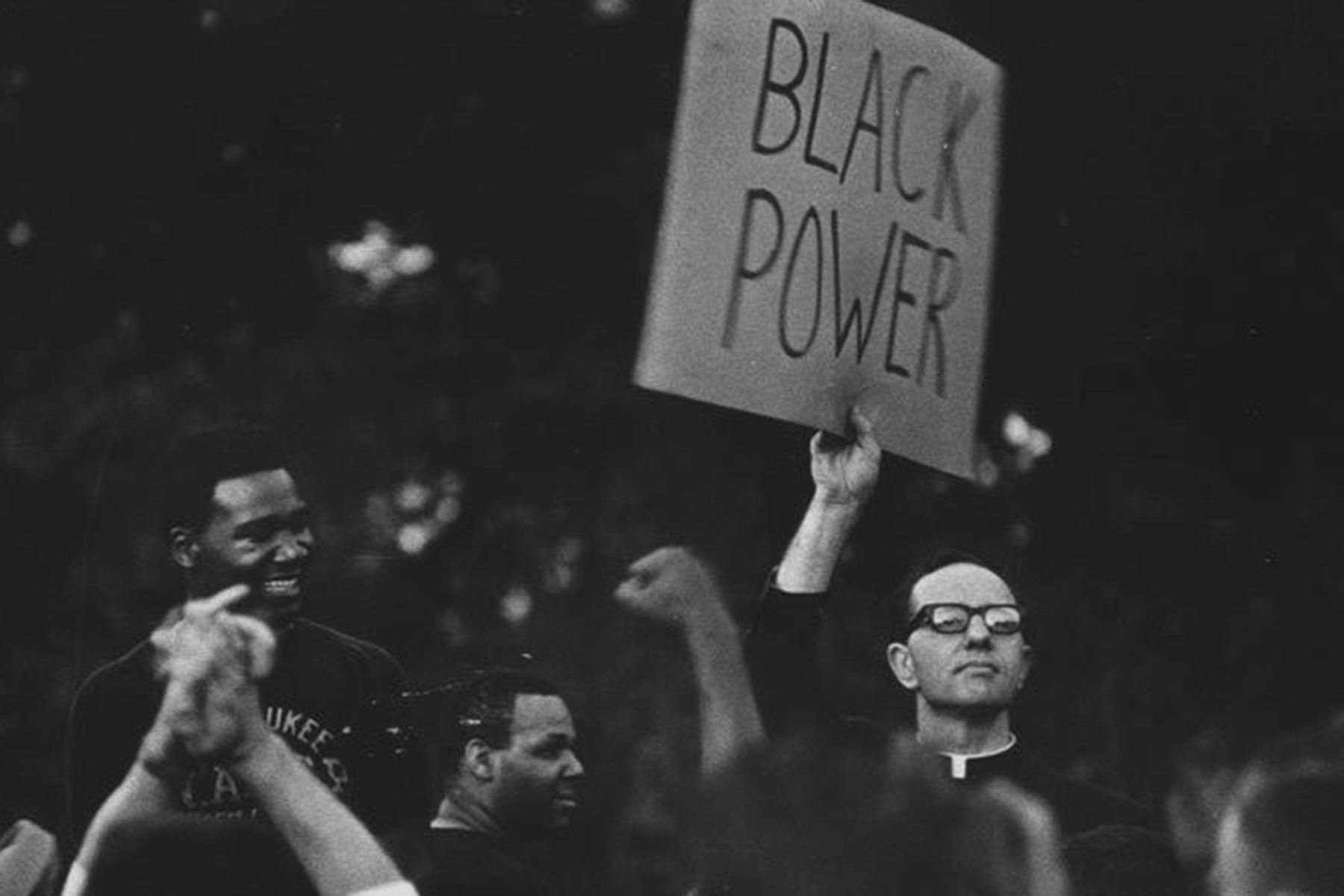

The next night, two hundred civil rights supporters again marched across the Sixteenth Street Viaduct, this time singing “freedom songs” and chanting Black Power slogans. Thirty Milwaukee police officers flanked the demonstrators, while police cars, television crews, and newspaper reporters from across the country trailed behind. A line of young black men wearing fatigues and grey sweatshirts emblazoned with the words “NAACP Commando” walked in formation between the marchers and police to maintain order and defend protesters.

At a South Side used auto lot, hundreds of young white toughs had gathered, rock ’n’ roll blared from loudspeakers, and an effigy of Father Groppi, defaced with a swastika, swung by the neck from a rope. Two men held a Confederate flag while others waved signs that read, “White Power,” “Bring Back Slavery,” “Trained Nigger,” and “Work, Don’t March.” Crowds estimated at ten to thirteen thousand lined the sidewalks and filled the blocks around Kosciuszko Park.

A steady hail of bottles, rocks, wood, firecrackers, urine, and spit rained down on protesters. Shouts of “We want slaves” and “kiII… kiII… kiII… kiII” were reported. At one intersection, hundreds of counter-demonstrators broke through the police line, rampaging over peaceful marchers and battling with the Commandos. Riot-clad police struggled to restore order. By the time marchers reached the park, thousands of whites had again closed in around them. When a small explosion injured a woman’s leg, open housing advocates beat a hasty and chaotic retreat back through the South Side and across the viaduct, as bands of angry white counter- demonstrators continued to attack.

When Father Groppi and Youth Council members arrived back at their North Side “Freedom House,” some tempers were hot. A large crowd of neighborhood people gathered, taunting police and throwing rocks and bottles. In the turmoil, police officers shot tear-gas into the run-down wooden Freedom House, causing it to catch fire. As Commandos scrambled to evacuate those inside, police blocked firefighters from the area, ensuring the total destruction of the house. Civil rights leaders believed police had purposely burned down the Freedom House in an attempt to intimidate them.

Following the first two nights of violent, “massive resistance” on the South Side near the Sixteenth Street Viaduct, Father Groppi put out an ecumenical call to people of conscience across the country to come and support the open housing campaign. As they had two years earlier in Selma, hundreds of people descended on Milwaukee to bear witness. Noting the religious tenor of the open housing campaign, as well as similarities between the images of violence near the viaduct and those of Southern voting rights activists beaten in Selma at the foot of the Edmund Pettus Bridge in 1965, some referred to Milwaukee as the “Selma of the North.”

Caught in the cross-currents of massive white resistance and a rising tide of Black Power militancy that was increasingly radical, racially exclusive, and less committed to nonviolence, many liberal activists embraced the Milwaukee campaign as “the last stand of an integrated, nonviolent, church-based movement” — a chance to redeem nonviolence in the urban North after the disappointing result in Chicago the previous year.

Milwaukee open housing advocates marched for two hundred consecutive nights, from the late summer of 1967 through the spring of 1968. Newspapers and magazines continued to cover the campaign. Father Groppi appeared on Meet the Press and other national news programs to discuss open housing and debate the militant nonviolent direct action campaign the Youth Council and Commandos led. The peculiar sight of a white Catholic priest at the forefront of a militant local civil rights struggle contributed to the broader debate over the meaning of Black Power, prompting comedian and activist, Dick Gregory, to state that the Milwaukee movement demonstrated that Black Power was “not a color, but an attitude.”

Father Groppi and several Youth Council and Commando leaders traveled the country meeting with activists and giving speeches. In the fall of 1967, a group of national religious organizations invited them to Washington, D.C. to headline a new congressional lobbying effort. Even Martin Luther King, Jr., sent a telegram to Groppi and Youth Council leaders stating that they had found “a middle ground between riots and sentimental supplications for justice.” He went on, “What you and your courageous associates are doing in Milwaukee will certainly serve as [an example of the] kind of massive nonviolence that we need in this turbulent period. You are demonstrating that it is possible to be militant and powerful without destroying life or property. Please know that you have my support and prayers.” All eyes seemed to be on Milwaukee in the fight for open housing.

During the holiday shopping season, the Youth Council and Commandos initiated an effective “Black Christmas” boycott of downtown stores to increase economic pressure on civic leaders. At the end of the year, Esquire named Father Groppi a “notable person” for 1967 and the Associated Press voted him the “newsmaker of the year” in religion. In January, the National NAACP honored the priest in New York for “the living demonstration he provides of the continuing need for interracial cooperation in the fight for freedom.” Then, in February of 1968, liberal Democratic Senators Walter Mondale and Edward Brooke announced a new legislative effort to pass a national housing bill. During debate on the floor of the Senate, Mondale raised up Milwaukee and the courageous, but to date futile, struggle of Father Groppi and the Youth Council as a prime example of the need for national action. In a follow-up letter, Mondale called the Milwaukee open housing campaign “most significant” to the push for congressional action.

Yet, despite accolades, national attention, and debate, white resistance in Milwaukee remained widespread and vociferous. White members of the Common Council refused to budge, seeing no political downside to their position. Democratic mayor Henry Maier dodged the issue by deflecting responsibility onto county and suburban governments. National and local real estate interests, supported by the Wisconsin-based John Birch Society and several new grassroots “closed housing” groups, placed ads in newspapers, distributed thousands of leaflets and spoke out publicly in defense of the “property owners’ rights.” The Ku Klux Klan and neo-Nazis made regular appearances during the demonstrations and periodically papered windshields and door handles across the city with white supremacist propaganda. Most significantly, thousands of local white residents continued to pour into the streets night after night to defend their neighborhoods and oppose racial change.

The thousands of letters Father Groppi received provide a unique window into white opposition to racial change in the North. The largest segment of letters was hate mail, including numerous death threats and frequent charges of “nigger lover” and “traitor.” Most appealed to racist or stereotyped thinking that cast African Americans as inherently lazy, immoral, stupid, dependent, criminal, and violent. Of those that provided what might be called constructive criticism, a majority held firm to the acculturation model, which stated that black migrants from the South did not possess the necessary skills to succeed in the urban North. Drawing on persistent Cold War fears, some made accusations of communist infiltration or outside agitation, while others criticized Black Power, racial exclusivity, and black nationalism.

A large number embraced an immigrant mythology that asked why African Americans should receive “special treatment” when their immigrant forerunners received no such help. These writers failed to acknowledge the many special measures that had, in fact, helped white ethnic immigrants and their progeny go to school, start a business, buy a home, or get a job. Still others played the old saw that open housing laws infringed on property rights. And Catholics continued to ask hard questions about the participation of nuns and priests in protests, as well as the future of the faith. A few expressed support for the goal of open housing, but attacked the use of confrontational nonviolent direct action and militant rhetoric. Intriguingly, much of the correspondence articulated a sense of white solidarity that was in sharp relief to the long history of white ethnic rivalry and conflict in Milwaukee and other American cities. And throughout, there is a pervasive sense of insecurity, or precariousness, in the face of large-scale economic and racial change.

The open housing movement culminated, locally and nationally, during the late spring of 1968. Many Milwaukeeans were exhausted from months of turmoil in city streets and searched for a way to reestablish order. By March, the open housing campaign was taking a toll on tourism and downtown commerce, prompting a chorus of political, civic, and business leaders to push for a compromise. At the same time, spring elections brought more liberal representation to the Common Council, another hopeful sign that the stalemate over open housing might be broken.

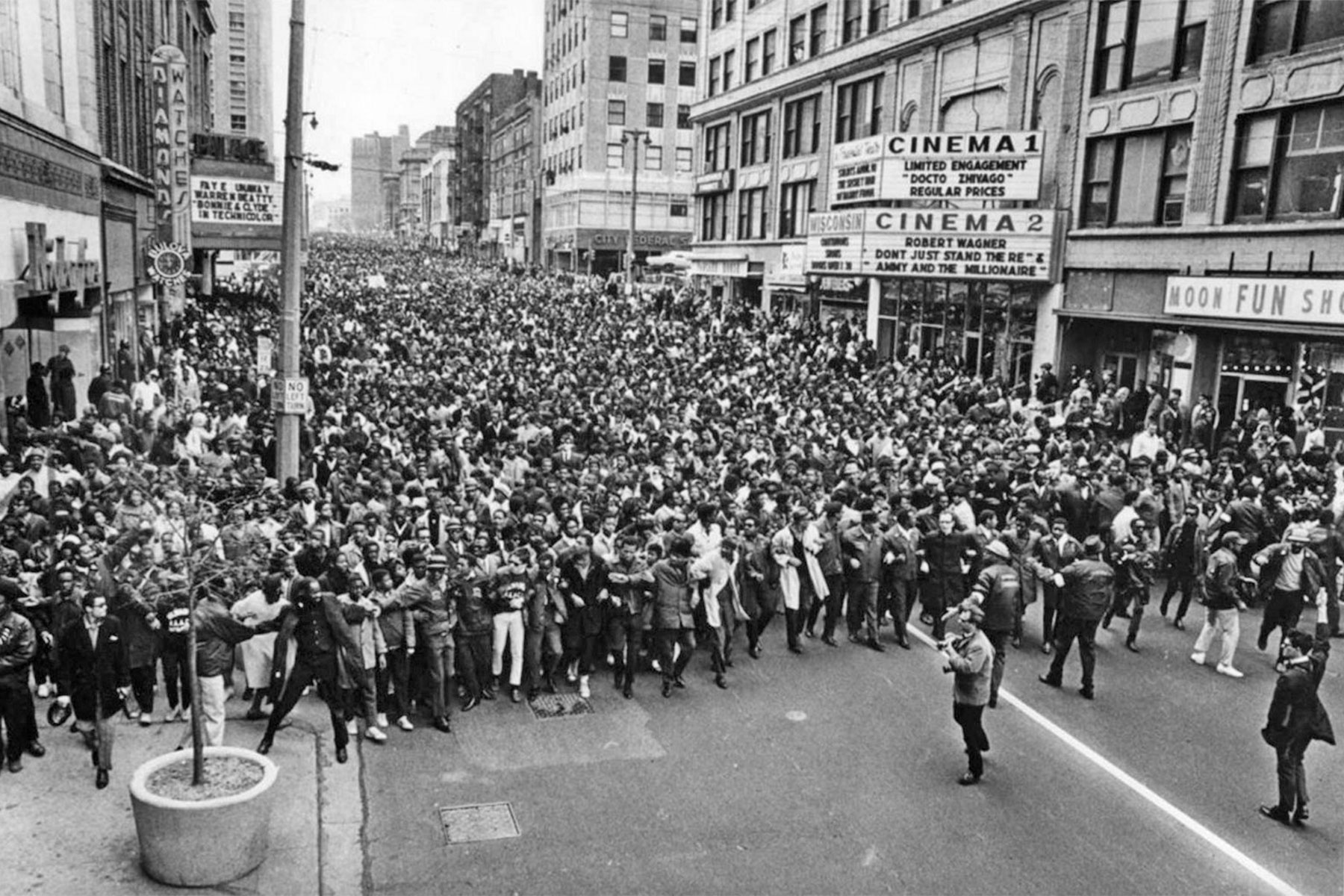

But it was Dr. King’s assassination on April 4th that finally tipped the political balance on the issue. Shocked that the nation’s leading advocate of nonviolence had been brutally slain, and reeling from the massive wave of urban violence that followed, Congress quickly passed the 1968 Civil Rights Act, which prohibited discrimination in the sale, rental, and financing of housing based on race, religion, and national origin. President Johnson signed the bill into law on April 11th, three days after more than twenty thousand Milwaukeeans marched through local streets in one of the largest peaceful demonstrations in the nation honoring King’s legacy. The Milwaukee Common Council, with seven new members, surprised many on April 30th by passing a citywide ordinance that surpassed the federal law and covered an estimated ninety percent of all Milwaukee dwellings. Father Groppi called the council’s vote “a significant victory,” but Vel Phillips was a bit more sardonic, concluding, “Even Milwaukee had to concede it was part of the United States.”

The Struggle for Fair Housing Continues

As significant as the 1968 Fair Housing Act was, and as much as the Milwaukee open housing campaign deserves its place in our national civil rights narrative, the story does not end there. Viewed through the lens of fifty years of hindsight, it is clear that local and national open housing legislation did not bring the hoped for integration of American society, or an end to housing discrimination. Over the ensuing decades, the promise of the Fair Housing Act has not been born out in American life.

Central to this failure has been the unwillingness of federal, state and local officials to strenuously enforce the terms of the act. As with so many gains of the 1960s-era, a new political conservatism has attacked and eroded institutional mechanisms designed to beat back America’s long, tragic history of racial discrimination in housing. City leaders, seeking to attract more affluent white residents back into inner-city neighborhoods, have sometimes foregone available federal housing funding to avoid compliance with fair housing regulations. Similarly, the real estate industry has continued to steer people of color toward different neighborhoods than white clients, reinforcing and perpetuating racial segregation.

Financial institutions still largely view communities of color as riskier investments, making home loans harder to get for black and brown Americans. When loans are granted, banks often extend worse terms to African American and Latino customers than they offer whites with similar income and credit history. And, despite telling pollsters that they are willing to live with black and brown people, large numbers of white Americans continue to abandon neighborhoods when African Americans, Latinos and other minorities move in.

Today, Milwaukee remains one of the most segregated cities in the United States. In fact, residential segregation is pervasive in almost every large and mid-sized American city today, with the most starkly segregated communities in the urban North. A 2010 Brown University study concluded that 90% of African Americans and Latinos would have to move to create truly racially balanced neighborhoods in the United States.

In 2017, Harvard Sociologist, Matthew Desmond, won a Pulitzer Prize for his important book, Evicted, which detailed the many ways property owners continue to exploit and profit from housing discrimination in Milwaukee. He is currently putting together a database that demonstrates that these policies are a national shame, not merely an isolated local phenomenon. And we know from various other social scientific studies that residential segregation continues to correlate with other ubiquitous inequalities in our society, including employment, education and health disparities.

Among other things, this history powerfully demonstrates that legislative change alone does not ensure non-discrimination, desegregation or social transformation. Rather, sustained and vigorous monitoring and enforcement is essential to making good on the promise of racial justice in America, whether it be in employment, education, housing, or other areas plagued by the long shadow of white supremacy. Fifty years after passage of the Fair Housing Act, Milwaukee still illustrates the dire circumstances facing the nation in housing. The question is whether we might learn from this past, rededicate ourselves to effective solutions and thereby refashion a future that is just and inclusive.

Patrick Jones

Milwaukee Public Library, Paul Shane / Associated Press, Sundance Film Festival / Bettmann Archive

Originally published on medium.com as Reckoning with the “Selma of the North” on the 50th Anniversary of the Fair Housing Act of 1968