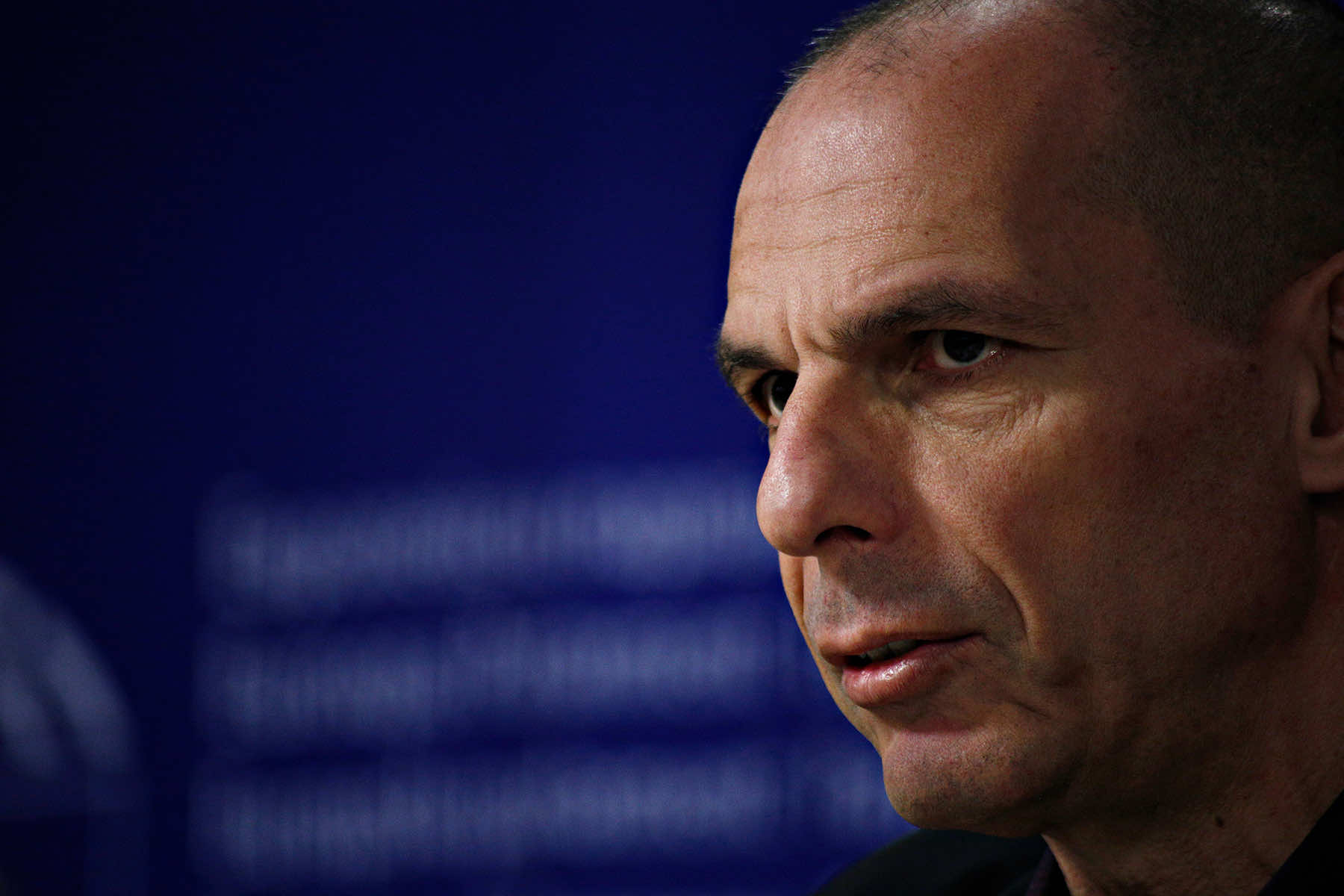

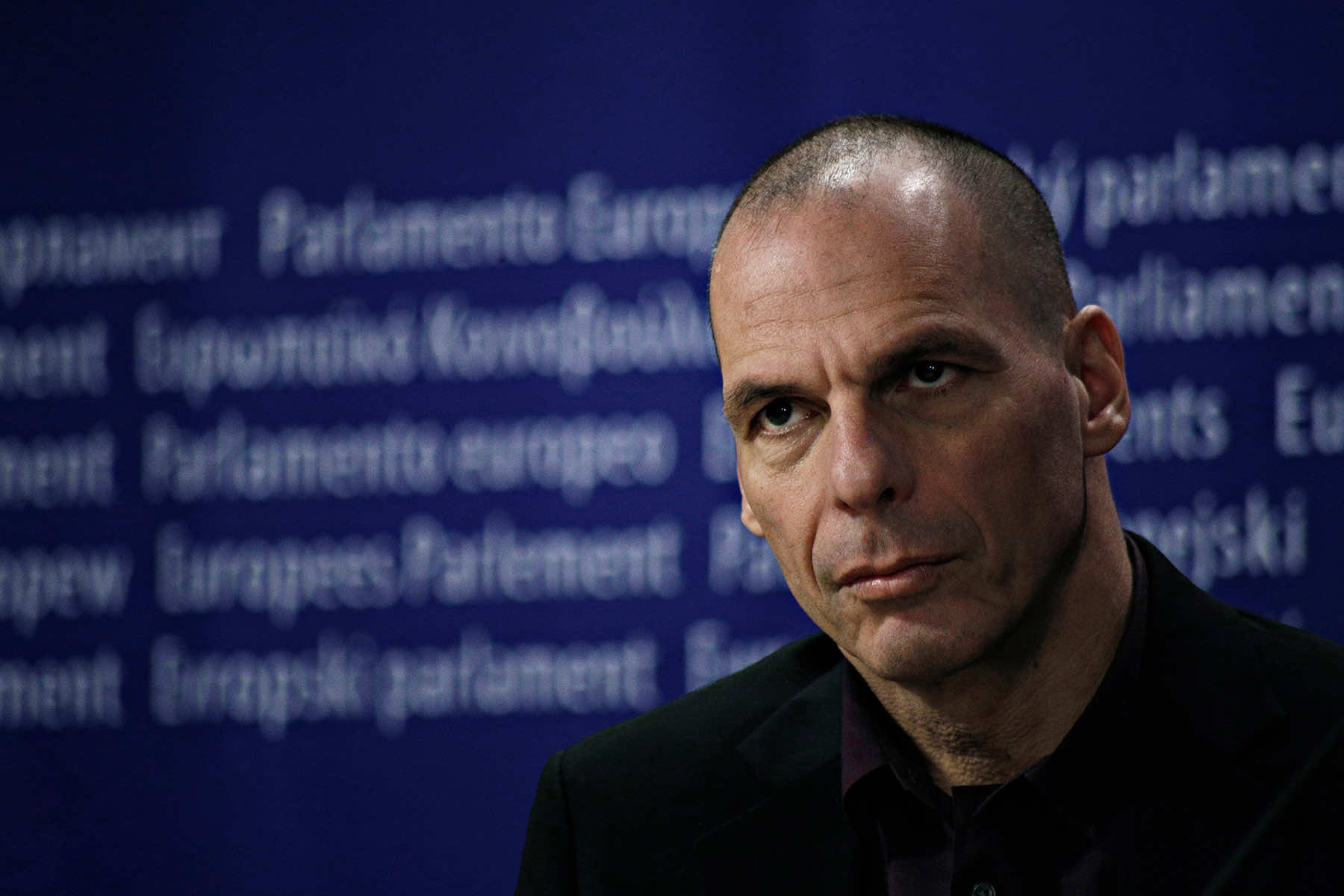

By Christopher Pollard, Tutor in Sociology and Philosophy, Deakin University

Yanis Varoufakis grew up during the Greek dictatorship of 1967-1974. He later became an economics professor and was briefly Greek finance minister in 2015.

His late father, a chemical engineer in a steel plant, instilled in his son a critical appreciation of how technology drives social change. He also instilled him with a belief that capitalism and genuine freedom were antithetical – a leftist politics that made his father a political prisoner for several years during the “junta”, as they called it.

In 1993, when he first got the internet, Varoufakis’s father posed a “killer question” to his son: “now computers speak to each other, will this network make capitalism impossible to overthrow? Or might it finally reveal its Achilles heel?”

Varoufakis has been mulling it over ever since. Though, sadly, it is now too late to explain to his father in person, Varoufakis’s new book Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism answers the question in the form of an extended reflection addressed to his father.

“Achilles heel” was on the right track. In his striking response, Varoufakis argues that we no longer live in a capitalist society; capitalism has morphed into a “technologically advanced form of feudalism.”

Rent over profit

Traditional capitalists are people who can use capital – defined as “anything that can be used to produce saleable goods” (such as factories, machinery, raw materials, money) – to coerce workers and generate income in the form of profits. Such capitalists are clearly still flourishing, but Varoufakis argues they are not driving the economy in the way they used to.

“In the early 19th century,” he wrote,

many feudal relations remained intact, but capitalist relations had begun to dominate. Today, capitalist relations remain intact, but techno-feudalist relations have begun to overtake them.

Traditional capitalists, he proposes, have become “vassal capitalists.” They are subordinate and dependent on a new breed of “lords” – the Big Tech companies – who generate enormous wealth via new digital platforms. A new form of algorithmic capital has evolved – what Varoufakis calls “cloud capital” – and it has displaced “capitalism’s two pillars: markets and profits.”

Markets have been “replaced by digital trading platforms which look like, but are not, markets.” The moment you enter amazon.com “you exit capitalism” and enter something that resembles a feudal fief: a digital world belonging to one man and his algorithm, which determines what products you will see and what products you won’t see.

If you are a seller, the platform will determine how you can sell and which customers you can approach. The terms in which you interact, share information and trade are dictated by an “algo” that “works for [Jeff Bezos’] bottom line.”

The capitalists who rely on this mode of selling are granted access to the digital estate by its virtual landowners, the Big Tech companies. And if “vassal capitalists” do not abide by the laws of the estate, they are kicked out – removed from Apple’s App Store or Google’s search index – with disastrous consequences for their business.

Access to the “digital fief” comes at the cost of exorbitant rents. Varoufakis notes that many third-party developers on the Apple store, for example, pay 30% “on all their revenues”, while Amazon charges its sellers “35% of revenues.” This, he argues, is like a medieval feudal lord sending round the sheriff to collect a large chunk of his serfs’ produce because he owns the estate and everything within it.

This is not extracting profit through the production or provision of goods and services, as these platforms are not a “service” in the sense in which the term is used in economics. They are extracting rents in the form of the huge cuts they take from the capitalists on their platforms.

There is “no disinterested invisible hand of the market” here. The Big Tech platforms are exempted from free-market competition. Their owners – “cloudalists” – increase their wealth and power at a dizzying pace with each click, exploiting a new form of rent-seeking made possible by the new algorithmically structured digital platforms. Parasitic on capitalist production, they are now dominating it.

Cloud serfs

But something even more transformative has happened, Varoufakis argues. Even though most of us are regularly interacting with capitalists and earning wages via our labour, now, for the first time in history, all of us contribute to “the wealth and power of the new ruling class” through our “unpaid labour.”

Every time we use our cloud-linked devices – smartphones, laptops, Alexa, Google Assistant, Siri – we replenish the capital of the Big Tech cloudalists. This in turn increases their capacity to generate more wealth. How? We train their algorithms, which train us, to train them, and so on, in a feedback loop whose goal is to shape our desires and behaviour. They are “selling things to us while selling our attention to others.”

This interaction, Varoufakis insists, is not taking place as any kind of market exchange, such as wages being paid by a capitalist to a group of workers. In this interaction, we are all high-tech “cloud serfs.”

The new advertising men of the postwar world, portrayed in the series Mad Men (Yanis is clearly a fan), thought television was amazing because of its power to deliver audiences to advertisers. They could innovate “attention-grabbing” ways of “manufacturing” consumer desires – and it was delivered free-to-air!

But, Varoufakis emphasises, the ad men of the previous century could never have imagined the development of something like Amazon’s Alexa: a digital network learning “at lightning speed”, via the input of millions of people, how to train us. It is shaping our desires and behaviours in a process of perpetual reinforcement. Our experience and reality are increasingly algorithmically curated. And due to the incredible ease and utility, the information is all freely given.

So the “cloud capital” we are generating for them all the time increases their capacity to generate yet more wealth, and thus increases their power – something we have only begun to realise. Approximately 80% of the income of traditional capitalist conglomerates go to salaries and wages, according to Varoufakis, while Big Tech’s workers, in contrast, collect “less than 1% of their firms’ revenues.”

Quantitative easing

So how did this dystopian turn happen without us really noticing the change? Varoufakis’s story is detailed, but he emphasises two main drivers.

First, the “internet commons” of Web 1.0 transformed into Web 2.0, privatised by American and Chinese Big Tech.

Second, the colossal sums of central bank money that were supposed to refloat our economies in the aftermath of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) – a process known as “quantitative easing” – were lent out to big business. Coupled with “austerity” economics for the many, this “murder[ed] investment” and led to what Varoufakis calls “gilded stagnation.”

Much of the central bank money, particularly following another round of quantitative easing during the COVID pandemic, made its way to the Big Tech companies. Their share prices soared to astronomical levels.

The “world of money” was decoupled from the “real economy” where most of us live and work. In an environment where profit became “optional”, loss-making Big Tech companies run by “intrepid and talented entrepreneurs” chose to build up their cloud capital.

So along with markets being steadily replaced by digital platforms, central bank money displaced private profits as the fuel that “fire[s] the global economy’s engine.” Intended by G7 central bankers and their presidents and prime ministers to “save capitalism”, it has unintentionally helped finance the emergence of a new form of capital (cloud capital) and a “new ruling class.”

GFC: the turning point

So why was the GFC such a pivotal point? Varoufakis has a lot to say. Crucial changes had taken place in our economies since the rise of large corporations in industry and banking, which grew ever bigger over the course of the 20th century, eventually becoming global in scale.

The Bretton Woods international financial system – designed to prevent the “greed-fuelled recklessness” that led to the 1929 crash, the Great Depression and a world war – was abolished in 1971. From the 1970s, economies were progressively deregulated and free-market policies were increasingly enthusiastically practised, leading to a new “financialised” version of capitalism.

This was facilitated by the suppression of workers’ wages and bargaining power. The weakened state was progressively captured by lobbyists for the interests of big business. And the hegemony of the US dollar in the global system led to a “tsunami” of dollars pouring back into US markets from Europe, Japan, and later China, “[enriching] America’s ruling class, despite its [large trade] deficit.”

By the new millennium, this had led to an orgy of speculation and, by 2007, the financiers, using “computer-generated complexity” to obscure the “gargantuan risks”, had “placed bets worth ten times more than humanity’s total income.”

The new version of capitalism was failing. But it had grown to such scale and in such a complex, integrated “globalised” way that the banks and insurance companies were “too big to fail.” Their collapse in 2008 would have taken down the US banking system, and the rest of the world with it. Their hubris was thus “rewarded with massive state bailouts.”

What could have happened, as in Sweden in the 1990s, was to “kick out” the bankers, nationalise the banks, appoint new directors and, years later, sell them to new owners – thus saving the banks, but not the bankers.

What happened instead was that bankers, handed large bailouts, did not direct the money to where it was most needed. Neither punished nor chastened, they sent it straight to Wall Street. And there it stayed. Combined with the profits sent to Wall Street from the rest of the world, it eventually caused an “everything rally” that went on for over a decade.

This ultimately helped fuel the development of the cloud capital that has overtaken capitalism. And every time we use our devices, we contribute to its value. The more we transact via platforms, the further we move away from an economic system primarily driven by markets and profits, and the more power concentrates “in the hands of even fewer individuals” – a “tiny band of multi-billionaires residing mostly in California or Shanghai.”

A tech-driven economic revolution

Varoufakis suggests his theory helps us better understand extreme wealth inequalities, the “atrophied democracies” and “poisoned politics” of the West, geopolitics (he interprets the United States and China as two rival “super cloud fiefs”), the stalling of the green energy revolution, and more.

For Varoufakis, we are not just living through a tech revolution, but a tech-driven economic revolution. He challenges us to come to terms with just what has happened to our economies – and our societies – in the era of Big Tech and Big Finance.

The first decades of the 21st century have brought challenges that we are still struggling to come to grips with. One thing is for sure – we have no hope of improving things without properly understanding our predicament.

This book is a welcome contribution towards that task. A technofeudalist age, Varoufakis argues, is not inevitable. Despite the difficulties we face, we have the agency to reject “techno dystopia” and structure our institutions in ways that more meaningfully embody freedom and democracy.

Towards the end of Technofeudalism, Varoufakis canvasses some proposals, drawn from his earlier book Another Now (2020), for how to address these issues. These include ending the cloudalists faux “free service” model and replacing it with a universal micro-payment model, instituting a Bill of Digital Rights, and using digital technology to “democratise companies” – with decisions being taken collectively by “employee-shareholders.”

Varoufakis also proposes to “democratise money.” This plan would involve central banks issuing digital wallets, a universal basic income, reconfiguring “the central bank’s ledger” in the direction of a “common payment and savings system”, and abolishing the current capacity of private banks to “create money.”

The proposals are pretty radical, but I think Varoukais would say they are as radical as the times require them to be.

Alexandros Michailidis and Gr. Siamidis (via Shutterstock)

Originally published on The Conversation under a Creative Commons license as Is capitalism dead? Yanis Varoufakis thinks it is – and he knows who killed it

Support evidence-based journalism with a tax-deductible donation today, make a contribution to The Conversation.