In 1845, an argument over who should pay for civic improvements escalated to the point that a cannon was wheeled out to threaten the west side of town with artillery fire.

The dispute ended in the wrecking of most of the bridges in town. They called it the Bridge War.

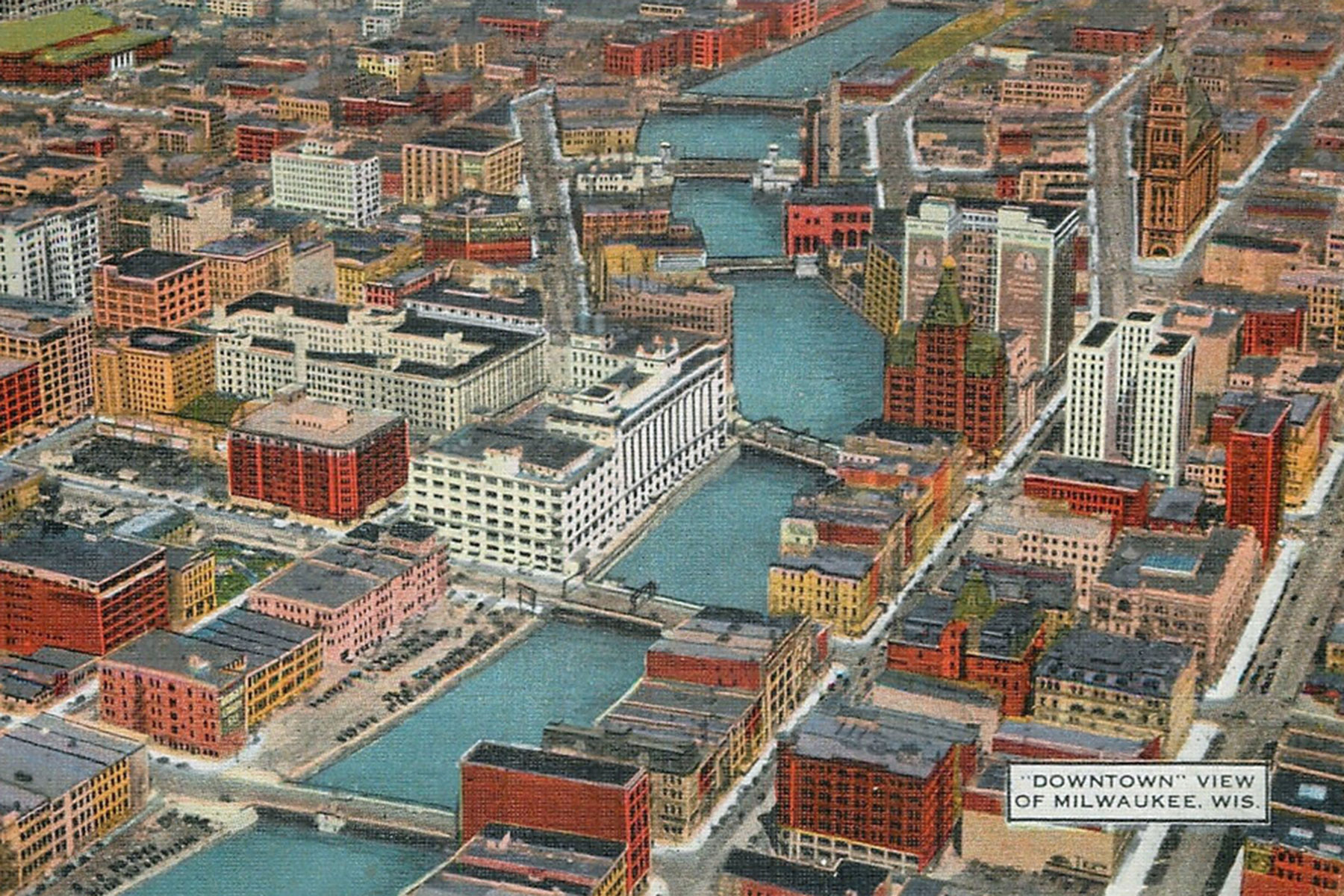

The dispute is all the more remarkable for Milwaukee, standing at the confluence of three rivers, is a city of bridges. A 1935 article in the Milwaukee Journal noted, “Milwaukeeans cross their bridges when they come to them – and they come to them, on the average, more than the inhabitants of any other American city. Milwaukee’s bridges carry more than 1,000,000 persons daily. The city has more movable bridges in proportion to its population than any other city in the land.”

In that Depression year, the paper counted nearly 100 spans ranging in length from the 3,919-foot Sixteenth Street viaduct to “spans over Lincoln creek that a lively frog could jump across.”

The roots of the 1845 Bridge War are intertwined with those of the city itself – the rivalry between residents of the East side founded by fur trader Solomon Juneau, and those living across the Milwaukee River in the West side village developed by Byron Kilbourn.

The first bridge to serve the future city was built by Kilbourn in 1835 across the Menomonee to link his community to the old Chicago trail. His next move was to construct a little steamboat, called the Menomonee, to meet ships in Milwaukee Bay and carry newcomers up the Milwaukee River – and land them on the West Side.

Having the first crack at the arriving settlers gave Kilbourn’s community an advantage. East siders soon remedied the matter by building, in 1840, the first bridge between the two communities at present-day Juneau Avenue. There were troubles with the site, however, and a new bridge was soon placed downstream at Wisconsin Avenue.

This bridge featured a floating span. Its design did not inspire confidence.

“It was averred that to cross it safely the teams had to start halfway up the hill and dash across with all possible speed before it sunk under them,” wrote A.C. Wheeler in his 1861 Chronicles of Milwaukee.

A flood carried away the bridge, and it was replaced with a much more robust floating span in 1843. In 1844, a third bridge was added at Wells Street.

Up to this point, most of the funding for Milwaukee River bridges was provided by East siders, Byron Kilbourn and the West siders seeing very little advantage to the bridges and having even less inclination to pay for them. The city government, such as it was, was unable to negotiate a compromise.

“The ten trustees representing the two wards met in common council but did very little in common,” Wheeler wrote. “There were two separate corporations to all intents (each tolerating the other), which formed the town government. They of the East side claimed the right to do as they pleased in regard to their locality, and the West side looked with jealous eye on any interference with their affairs.”

With the completion of the Wells Street bridge, the dispute turned serious.

“The worthy folk of Kilbourntown said they had not the remotest idea of paying for what they didn’t want, but what, in their opinion, was a nuisance. Thus matters ran along until the spring of 1845 when the badinage and sarcasm which had been shot across the unconscious waters were turned into threats of deeper meaning,” he wrote.

On May 3, 1845, a schooner collided with the Wisconsin Avenue bridge, heavily damaging the structure. Four days later, in a late-night council meeting, Kilbourn rushed through a resolution to also take the original Milwaukee River span at present-day Juneau Avenue out of service. This bridge was, his supporters said, out of use, out of repair, and an “insupportable nuisance.”

Under Kilbourn’s resolution, the Committee on Streets and Bridges in the West Ward was directed to immediately remove the western approach to the bridge. This was done the following morning, resulting in a bridge that extended across the river and stopped just short of touching the west bank.

East siders wakened to the startling news and hurried to the scene.

Wheeler wrote, “Sure enough a score of men, with teams, were digging away manfully at the street on the west side, and fast rendering all connection, between the apron of the bridge and the bank, a matter of history and memory only.”

This, to the residents of the East Side, was nothing less than the reckless destruction of public property, and the crowd soon worked itself into a frenzy.

“The mob shouted like wild beasts, and seemed to sway and toss about in a mad delirium of purpose,” Wheeler recalled.

Carried away by their rage, the crowd dragged a cannon down to the river, stuffed it with clock weights, and took aim at Kilbourn’s house on the opposite bank.

At this moment, Jonathan E. Arnold, a respected resident of the East side appeared on the scene with the news that Kilbourn’s daughter had died that morning and was at that moment lying in a coffin in Kilbourn’s house surrounded by mourners.

Any man who would tear a father from the corpse of his daughter, Arnold thundered to the mob, deserved to be branded a coward and a savage.

Bloodshed was thus averted by the thinnest of margins, but the Bridge War was not quite over.

The common council hammered out an agreement to repair the bridge, but on May 28, 1845, East side residents gathered to debate the bridge question. The discussion got out of hand, a mob formed, and marched to Wisconsin Avenue they proceeded to destroy the draw mechanism. Onward to the Menomonee Bridge they marched. Damage to that bridge proved minor, although Wheeler reported a man armed with an ax was so carried away with hacking at a log dragged from the bridge that he literally foamed at the mouth.

“Having vented their spite on the inoffensive timbers, this crowd of citizens immediately felt better,” Wheeler added. “Some of them laughed, others joked, and all of them came out in the best of spirits, as though they felt ashamed of themselves, and were laughing at their own folly.”

Gradually the months passed, passions cooled, and a desire took hold to settle the issue peacefully. On December 31st, 1845, the council met and passed resolutions concerned with the construction and maintenance of bridges, and the equitable sharing of costs. The resolutions concluded with these words, “It shall be, and is hereby expressly understood and agreed, that the ‘vexed question’ in relation to bridges between the East and West Wards, is permanently and forever settled, and the faith of the said wards pledged to carry said resolutions into effect.”

“In looking back to the time when this occurred, from today, how perfectly foolish the whole proceeding appears,” wrote Milwaukee settler James S. Buck in his 1881 Pioneer History of Milwaukee. “Every act connected with the settlement of the bridge question goes to show how little real conception of what the future of Milwaukee was to be, was possessed by any of the actors in that drama.”

The old rivalry between the east and west settlements can be seen today. Downtown bridges still cross the river at an angle because the East and West streets do not line up. James Buck places the blame for this squarely on Byron Kilbourn.

“Kilbourn, from the first start,” Buck wrote. “never intended that any communication by bridges should exist between the East and West Side, and acting upon that principle, made his survey in such a manner as to prevent the streets upon the two sides from matching each other, always insisting that the West Side did not want, and, if he could prevent it, should never have any communication with the East, except by boats.

“It was a great mistake, marring the beauty and symmetry of the city, for all time, as it is too late now to correct it,” Buck wrote. “This, for a man of Mr. Kilbourn’s ability, was a most stupendous piece of folly.”

Carl Swanson, Milwaukee Notebook

Carl A. Swanson collection and Apple Maps

Originally published on Milwaukee Notebook as Milwaukee’s Bridge War