Some Wisconsin counties use risk assessment tools to predict who will skip out on court or commit new crimes but critics say there are better ways to cut incarceration.

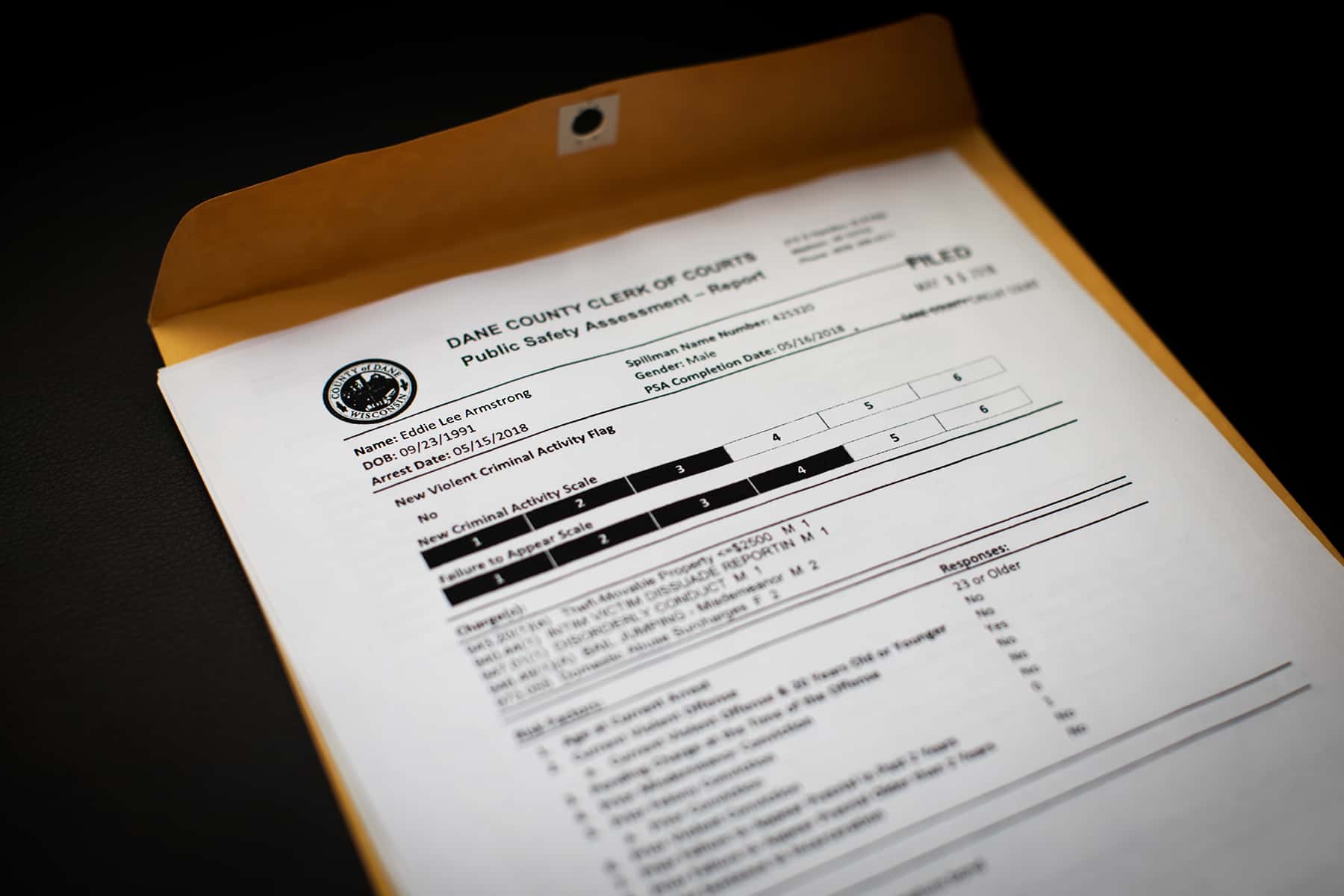

Eddie Armstrong had been sitting in the Dane County Jail for nearly two weeks when a judge set him free to await trial. His release was based in part on computer-generated scores that rated Armstrong’s likelihood to return to court as fair and predicted he had a good chance of not committing a new crime. Locked away from his fiancé and three children, Armstrong said, he was “going crazy.”

“I was in there — felt like I was gonna die,” said Armstrong, 27. “I didn’t even want to eat no more. Their food is nasty, worst food you probably could ever get in the world.”

After 11 days in jail, Armstrong finally got his bail hearing on May 25. If the court commissioner granted a signature bond, Armstrong would be free to go home to await trial. All he had to do was sign a promise that he would return to court.

But if the court commissioner set a bail amount that he could not afford, Armstrong would spend more time in jail — even though he was presumed innocent. Armstrong’s attorney, Blake Duren, appointed by the public defender’s office, said it was unlikely his client would have been able to come up with bail. Spending time locked up awaiting trial is a familiar story for low-income defendants across the nation.

On any given day in the United States, around half a million people are held in jail awaiting trial — a trend that has grown sharply since the 1980s, according to the Prison Policy Initiative, a nonprofit that researches mass criminalization. Some poor defendants can spend days, weeks or even years behind bars, just waiting for their day in court, while rich defendants remain free.

Research shows even short jail stays can have devastating impacts on the accused, including job loss, missed rent payments, lost time with children or feeling pressured to plead guilty to a crime they did not commit. Such consequences are causing states to rethink the use of cash bail. This includes Wisconsin, where a legislative study committee is considering substantial changes to the state’s pretrial system.

On this day, Dane County Circuit Court Commissioner Brian Asmus ordered a signature bond, and Armstrong was released. But it was not an easy decision. Armstrong had three pending misdemeanor cases in which he faced multiple charges, one of which stemmed from a physical fight with his fiancé on May 15. According to the criminal complaint, Armstrong threw her to the floor, punched her and took the phone out of her hand when she called 911. He also missed one of his court dates.

At his hearing, Armstrong stood quietly in a pale blue jail uniform as he listened to law intern Kelly Orth, representing the Dane County District Attorney’s Office, argue that he should pay a $300 cash bond for his freedom. Assistant state public defender Stanley Woodard asked that he be given a “second chance” on signature bond instead.

“Well, I think it’s a close call,” Asmus said. “I’ll order a signature bond and go along with the Public Safety Assessment.”

Data-driven justice

Adopted on a trial basis by the Dane County Circuit Court, the Public Safety Assessment, or the PSA, is a computer algorithm that uses defendants’ criminal history and past performance in court to predict the risk of them committing a new crime or failing to appear in court. The PSA is one of many of these statistical tools, called pretrial risk assessments, that are being used across the nation.

The tool rated Armstrong as a 3 out of 6 in terms of the probability that he would be arrested for a new crime, with 6 being the riskiest. He was rated a 4 out of 6 for how likely he was to fail to appear for his next court date. Armstrong was not flagged as someone who had a risk of committing a new violent crime.

Based on these risk scores, the PSA recommended that Armstrong be given a signature bond with no conditions. And two months later, Armstrong did show up for court, family in tow, with no new crimes on his record. In this case, it appeared, the PSA helped the court commissioner make the right call.

But a little more than two months after that, on Oct. 5, Armstrong broke his promise. His final hearing, where he was to be sentenced in all three of his cases, was scheduled for 10 a.m. By 10:33 a.m., Armstrong still had not shown up, and his hearing was officially canceled.

Later that day, though, Armstrong came to court. He thought the hearing was scheduled for the afternoon. The court cancelled a planned warrant for his arrest and rescheduled the hearing. This time, he showed up on time and was sentenced to 30 days for theft and disorderly conduct. The rest of his charges were dismissed.

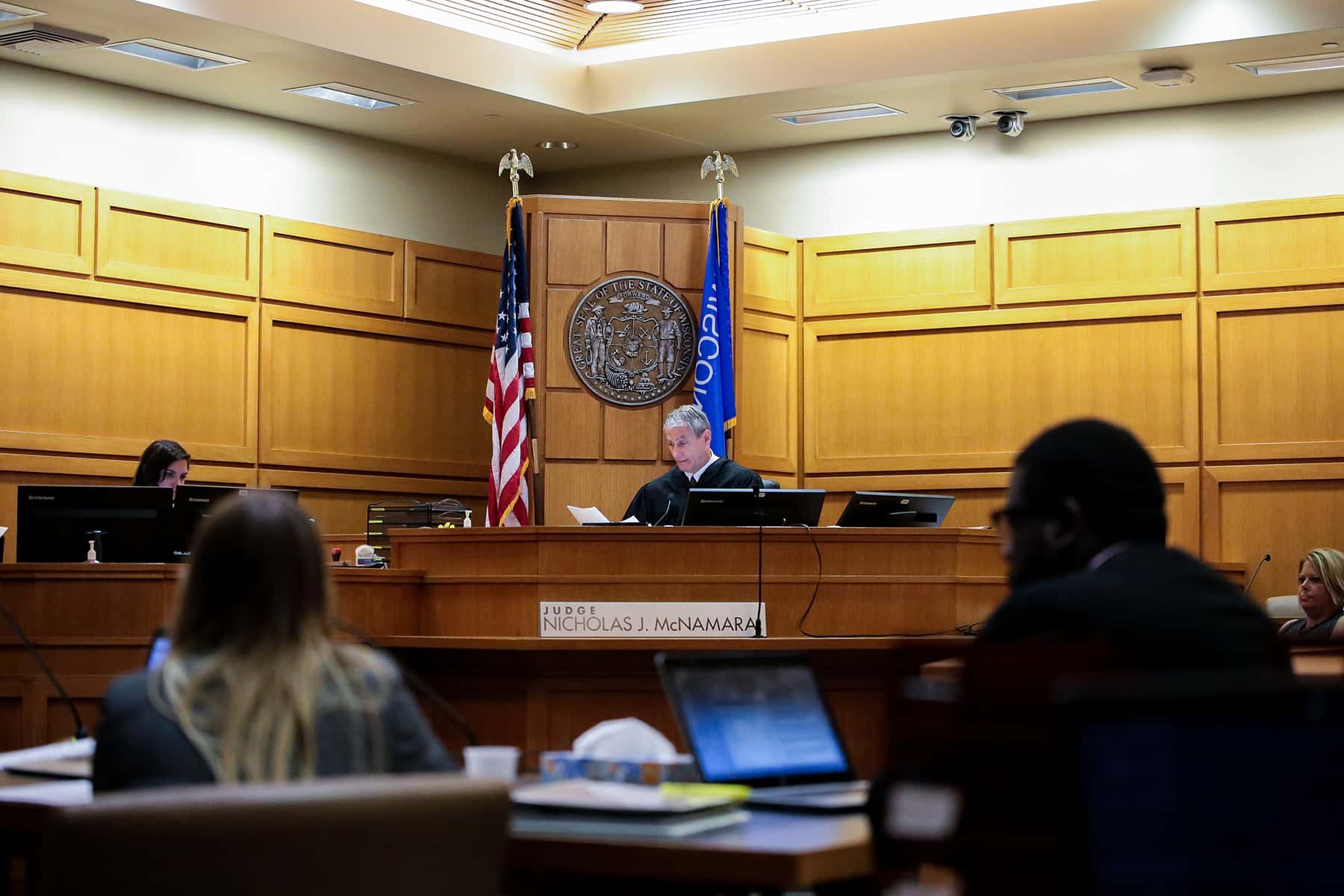

“One problem is that some people think a risk assessment is like a Magic 8 Ball that works,” Dane County Circuit Judge Nicholas McNamara said. “Or it’s like a crystal ball that works, and lets you see the future. That’s not what risk assessments do.”

States rethinking bail

As states rethink the use of bail, pretrial risk assessment tools are often at the center of it. In New Jersey, lawmakers got rid of cash bail almost entirely, prompting judges to release more defendants in line with the PSA’s recommendations.

A Wisconsin legislative study committee has drafted changes to the way Wisconsin’s pretrial system operates. At a Jan. 29 meeting, there was general agreement among committee members to move the proposals forward. The Joint Legislative Council, which creates committees to study problems identified by the Legislature, would make the final decision on whether to introduce the measures.

Among the proposals are bills that would make cash bail harder to use and allow judges to preventatively detain potentially dangerous defendants without bail. Both proposals are contingent on passage of a constitutional amendment, which must be approved by two consecutive Legislatures, the governor and, finally, a statewide referendum. That means those changes would be more than two years away.

One of the bills not dependent on the amendment would make it clear in Wisconsin law that judges are allowed to consider the results of a validated pretrial risk assessment during bail hearings — tools already in use in Dane and Milwaukee counties.

Seven other counties — Chippewa, Eau Claire, La Crosse, Marathon, Outagamie, Rock and Waukesha — have agreed to pilot the PSA. Other counties across the state have expressed interest in implementing such tools, said Constance Kostelac, director of the state Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Information and Analysis.

The idea is that these data-driven tools can help judges better identify low-risk defendants who can be released without bail, saving them from additional disruption and punishment and saving taxpayers the cost of incarceration. Judges then detain or assign bail only to the riskiest defendants. But in the criminal justice system, the use of algorithms to aid in decision-making has sparked debate.

A common concern is that racial biases could creep into the calculation, exacerbating existing racial disparities within the system. Others argue there is not enough evidence to prove the tools are actually effective, and stakeholders should focus on other bail reform strategies, such as automatic pretrial release of misdemeanor or nonviolent offenders.

With these concerns in mind, nearly 120 criminal justice organizations signed a July 30 statement standing against the use of pretrial risk assessment tools, arguing jurisdictions should instead “decarcerate most accused people pretrial.” Proponents say even if risk assessments are flawed, they still might be an improvement on the way judges currently make decisions.

The tools could help move pretrial systems “from being really, really, really bad, to less bad and on the road to better,” said Kit Kerschensteiner, director of legal and advocacy services of Disability Rights Wisconsin and a member of a committee examining ways to bring more evidence-based practices into Wisconsin’s criminal justice system.

On the other hand, if authorities are not careful about how they use pretrial risk assessment tools, it could undermine efforts to stop jailing people just because they are too poor to afford bail.

Use of pretrial algorithms expands

As of 2017, about 20 percent of Americans, and 26 percent of Wisconsin residents, lived in a jurisdiction that used a scientifically validated pretrial risk assessment tool, according to the Pretrial Justice Institute, a Maryland-based group that advocates for “fair and effective” pretrial practices.

From 2012 to 2017, 28 states enacted laws relating to the use of risk assessment tools during pretrial, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. More than a dozen states — including Utah in 2018 — have authorized such a tool statewide.

In July, the PSA, the most commonly used tool, was released nationally for any jurisdiction to adopt. Arnold Ventures, formerly known as the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, which developed the tool, made it available on the PSA’s website for free, along with guidance on how to implement it.

“My general impression is that the world of pretrial is moving very, very quickly towards mass adoption of the Public Safety Assessment,” said Logan Koepke, senior policy analyst at Upturn, a nonprofit that researches and advocates for technologies that promote equity in the criminal justice system.

Why use risk assessment tools at all?

It is not hard to see why some criminal justice advocates are excited about the algorithms. Pretrial is a tough spot in the criminal justice system, McNamara, the Dane County judge, said. Judges have to balance the liberty of people who are presumed innocent with the potential danger to the public of releasing someone whom police have apprehended.

The first time McNamara released a defendant because the man was sitting for “too long” and was simply “too poor” to post cash bail was when McNamara was a new judge in 2009. Eight hours after the defendant was released, the man stabbed his brother.

“The public, defendants, everybody, don’t want to hear a judge say ‘I don’t know,’ ” McNamara said. “But I personally, admit I don’t know. I don’t know the future. I don’t know human nature. And even defendants themselves don’t know those things. They may not know that right as soon as they get a chance, they’re going to repeat some of the same behavior that was intolerable.”

Jeremy Travis, executive vice president of criminal justice at Arnold Ventures, said decisions made by judges about whether to assign cash bail are “highly subjective and reflexive” and “made in only a matter of minutes with potentially life-changing consequences for the person who’s held.”

Risk assessment tools, on the other hand, can cut through psychological biases that humans have, said Chris Griffin, visiting professor and research scholar at University of Arizona’s law school. Instead of relying on an “amorphous” impression of a defendant, a judge can look at a defendant’s “demonstrated, empirical, objective risk.”

And research shows the vast majority of defendants are not that risky. In Kentucky, from July 1, 2013 to Dec. 30, 2014, when the PSA was first implemented, 85.2 percent of those who were released pretrial showed up for their court dates, 89.4 percent did not commit a new crime and 98.9 percent did not commit a new violent crime, according to a study of the PSA.

Nevertheless, the researchers concluded that “risk assessments are not silver bullets, but rather decision-making tools that require ongoing refinement.” At the very least, McNamara said, these tools give judges more information.

“Most research has shown that … an informed human judgment together with an objective risk analysis produces better outcomes that appear to be more accurate and more fair,” McNamara said.

‘Jury’s still out’ on effectiveness

Upturn’s Koepke, who recently wrote a paper on the potential dangers of using risk assessment tools, said people tend to assume the tools work since they are based on data and statistics. But Koepke said the “jury’s still out” on whether they maximize public safety and court attendance while decreasing the number of people held pretrial.

Megan Stevenson, an assistant law professor at George Mason University, said risk assessments have a “glossy veneer of science” but there is a “sore lack of research” showing their effectiveness. In a recent paper published in the Minnesota Law Review, Stevenson wrote that when the assessments improve one outcome, like release rates, they can negatively impact another, such as appearances in court.

Early data, however, show jurisdictions have seen success, including New Jersey, which implemented PSAs statewide in January 2017. New Jersey’s pretrial population decreased by 43.9 percent from December 2015 to December 2018 after it began using the PSA, according to data from the New Jersey Courts. At the same time, crime rates in New Jersey decreased, the state reported.

Similar results were seen in Lucas County, Ohio, which implemented the PSA in January 2015. By August 2016, the proportion of pretrial defendants released on their own recognizance nearly doubled, while pretrial crime was cut in half. Among all defendants who were released pretrial, the proportion that were re-arrested while released was cut from 20 percent to 10 percent. The percentage of defendants skipping their court dates was “dramatically reduced,” Arnold Ventures reported.

Koepke countered that for research done in jurisdictions where multiple reform efforts are underway, it may not be clear which one is driving positive change. In New Jersey, for example, pretrial incarceration was decreasing before the PSA was put in place, he said.

Philadelphia reduced its jail population by more than 30 percent and plans to close one of its jails — all without risk assessment, said Mark Houldin, policy director for the Defender Association of Philadelphia.

Sharad Goel, an assistant professor at Stanford University in management science and engineering, said he thinks most criminologists would agree the evidence suggests risk assessment works but is not definitive.

“Generally,” he said, “fewer people are detained, and crime rates don’t go up.”

Waukesha County Circuit Court Chief Judge Jennifer Dorow said her sheriff, district attorney, public defender, court commissioner and herself disagree on many things in the bail system — but not risk assessment.

“There was one thing we were all in agreement on,” Dorow said. “And that was, it was far better to have a risk assessment tool than to not have one at all — that it was that valuable of a piece of information.”

But Houldin said risk assessments typically bring “harmful effects,” and jurisdictions should look first at other reforms that could reduce their pretrial jail populations.

Dane County research continues

In Dane County, Harvard’s Access to Justice Lab is conducting a randomized control trial — a method often called the “gold standard” of empirical research — to test whether the PSA is effective, said Griffin, who is the former research director at Harvard Law School’s Access to Justice Lab and continues to help lead the research in Dane County.

As part of the trial, which started in 2017, the PSA is used in nearly half of Dane County criminal cases, creating a “world” with the PSA and a “world” without it. Griffin said researchers will then compare the two to see if the PSA improves judges’ decisions. This method mitigates the muddying effects of time and multiple reform efforts happening at once.

Griffin said the anticipated result is the “best possible evidence” of the effectiveness of the PSA, but the final report is not expected until 2022. Asked whether the tool is working in Dane County, Griffin said, “It would be too anecdotal and too premature to draw such conclusions.”

Overestimating risk?

Koepke said risk assessments may overestimate a defendant’s risk by failing to factor in recent bail changes — such as text message reminders or limiting cash bail — that can make people less likely to skip out on court or commit crime. Studies show long pretrial jail stays correlate to more criminality later on.

Colorado, for example, reformed its bail system in May 2013 but is still using a risk assessment tool based on data from before October 2012 — prior to the changes being enacted. According to Koepke’s analysis, defendants showed up for court more often than the tool predicted.

Houldin said when someone is labeled high risk it “becomes a defining characteristic of that person.” In Philadelphia, Houldin said, 95 percent of juveniles who were labeled as high risk by a pretrial risk assessment were detained.

Judges also might “level up” their judgment to ensure public safety, Koepke said. That could lead to more people being locked up or getting more conditions of release.

Koepke said he sees signs of this overestimation effect happening in New Jersey. Many more people than expected are being released with stringent conditions, such as electronic monitoring or frequent in-person check-ins.

Having more people placed under electronic monitoring is “trading one injustice for another,” said Vanita Gupta, president and CEO of The Leadership Conference Education Fund, which organized the July statement standing against risk assessment.

Said Koepke: “Reformers might be looking around like, ‘Hey what happened? Why are we still at the exact same percentage of failure to appear rate and re-arrest rate even though we’ve completely tried to revolutionize our system?’ ”

Proceed with caution

Almost all groups agree important precautions need to be taken if a jurisdiction chooses to move forward with risk assessments.

Criminal justice leaders say they should complement other information, such as arguments from prosecutors and defense attorneys. Algorithms also should be tested on the local population for accuracy and continually reassessed for problems, including racial bias. Most of all, those critical of risk assessments say they should not be used to lock more people up.

Gupta said risk assessment is not a “panacea” for bail reform, adding, “We can’t simply end money bail and replace it with these tools.”

Koepke said counties should focus on other changes such as expanding pretrial services or limiting cash bail, which he said are more effective at reducing pretrial jail populations. Pretrial services help defendants show up for court and comply with conditions of release by providing text, phone call or written reminders, in-person check-ins, electronic monitoring, and drug and alcohol testing.

State Rep. Evan Goyke, D-Milwaukee, and Sen. Van Wanggaard, R-Racine, members of the Wisconsin study committee, said they will work together to draft legislation to provide funding for such services across Wisconsin.

Said Travis of Arnold Ventures: “Risk assessment can help make decisions about who should be in, who should be out — but it (bail reform) is much bigger than an algorithm.”

Emily Hamer

Emily Hamer and Katie Scheidt

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.