“The ability to control is different from the ability to govern.” – Chen Tianyong

Could the COVID-19 surge in China unleash a new coronavirus mutant on the world? Scientists do not know but worry that might happen. It could be similar to omicron variants circulating there now. It could be a combination of strains. Or something entirely different, they say.

“China has a population that is very large and there’s limited immunity. And that seems to be the setting in which we may see an explosion of a new variant,” said Dr. Stuart Campbell Ray, an infectious disease expert at Johns Hopkins University.

Every new infection offers a chance for the coronavirus to mutate, and the virus is spreading rapidly in China. The country of 1.4 billion has largely abandoned its “zero COVID” policy.

Though overall reported vaccination rates are high, booster levels are lower, especially among older people. Domestic vaccines have proven less effective against serious infection than Western-made messenger RNA versions. Many were given more than a year ago, meaning immunity has waned. The result? Fertile ground for the virus to change.

“When we’ve seen big waves of infection, it’s often followed by new variants being generated,” Ray said.

About three years ago, the original version of the coronavirus spread from China to the rest of the world and was eventually replaced by the delta variant, then omicron and its descendants, which continue plaguing the world today.

Dr. Shan-Lu Liu, who studies viruses at Ohio State University, said many existing omicron variants have been detected in China, including BF.7, which is extremely adept at evading immunity and is believed to be driving the current surge.

Experts said a partially immune population like China’s puts particular pressure on the virus to change. Ray compared the virus to a boxer that “learns to evade the skills that you have and adapt to get around those.”

One big unknown is whether a new variant will cause more severe disease. Experts say there’s no inherent biological reason the virus has to become milder over time.

“Much of the mildness we’ve experienced over the past six to 12 months in many parts of the world has been due to accumulated immunity either through vaccination or infection, not because the virus has changed” in severity, Ray said.

In China, most people have never been exposed to the coronavirus. China’s vaccines rely on an older technology producing fewer antibodies than messenger RNA vaccines.

Given those realities, Dr. Gagandeep Kang, who studies viruses at the Christian Medical College in Vellore, India, said it remains to be seen if the virus will follow the same pattern of evolution in China as it has in the rest of the world after vaccines came out. “Or,” she asked, “will the pattern of evolution be completely different?”

Recently, the World Health Organization expressed concern about reports of severe disease in China. Around the cities of Baoding and Langfang outside Beijing, hospitals have run out of intensive care beds and staff as severe cases surge.

China’s plan to track the virus centers around three city hospitals in each province, where samples will be collected from walk-in patients who are very sick and all those who die every week, said Xu Wenbo of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

He said 50 of the 130 omicron versions detected in China had resulted in outbreaks. The country is creating a national genetic database “to monitor in real time” how different strains were evolving and the potential implications for public health, he said.

At this point, however, there is limited information about genetic viral sequencing coming out of China, said Jeremy Luban, a virologist at the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

“We don’t know all of what’s going on,” Luban said. But clearly, “the pandemic is not over.”

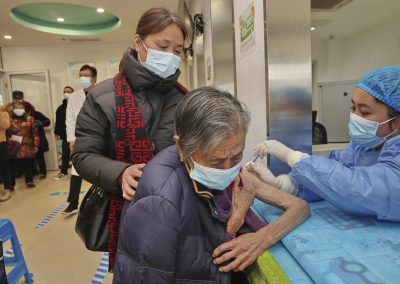

While China races to vaccinate elderly, many are reluctant. Chinese authorities have been going door to door and paying people older than 60 to get vaccinated against COVID-19.

But even as cases surge, 64-year-old Li Liansheng said his friends are alarmed by stories of fevers, blood clots and other side effects.

“When people hear about such incidents, they may not be willing to take the vaccines,” said Li, who had been vaccinated before he caught COVID-19. A few days after his 10-day bout with the virus, Li is nursing a sore throat and cough. He said it was like a “normal cold” with a mild fever.

China has joined other countries in treating cases instead of trying to stamp out virus transmission by dropping or easing rules on testing, quarantines and movement as it tries to reverse an economic slump. But the shift has flooded hospitals with feverish, wheezing patients.

The National Health Commission announced a campaign in November to raise the vaccination rate among older Chinese, which health experts say is crucial to avoiding a health care crisis. It’s also the biggest hurdle before the ruling Communist Party can lift the last of the world’s most stringent antivirus restrictions.

China kept case numbers low for two years with a “zero-COVID” strategy that isolated cities and confined millions of people to their homes. Now, as it backs off that approach, it is facing the widespread outbreaks that other countries have already gone through.

The health commission has recorded only six COVID-19 fatalities this month, bringing the country’s official toll to 5,241. That is despite multiple reports by families of relatives dying.

China only counts deaths from pneumonia or respiratory failure in its official COVID-19 toll, a health official said last week. That unusually narrow definition excludes many deaths other countries would attribute to COVID-19. Experts have forecast 1 to 2 million deaths in China through the end of 2023.

Li, who was exercising at the leafy grounds of central Beijing’s Temple of Heaven, said he is considering getting a second booster due to the publicity campaign: “As long as we know the vaccine won’t cause big side effects, we should take it.”

Neighborhood committees that form the lowest level of government have been ordered to find everyone 65 and older and keep track of their health. They are doing what state media call the “ideological work” of lobbying residents to persuade elderly relatives to get vaccinated.

In Beijing, the Chinese capital, the Liulidun neighborhood is promising people over 60 up to 500 yuan ($70) to get a two-dose vaccination course and one booster.

The National Health Commission announced in December the number of people being vaccinated daily had more than doubled to 3.5 million nationwide. But that still is a small fraction of the tens of millions of shots that were being administered every day in early 2021.

Older people are put off by potential side effects of Chinese-made vaccines, for which the government hasn’t announced results of testing on people in their 60s and older.

Li said a 55-year-old friend suffered fevers and blood clots after being vaccinated. He said they can’t be sure the shot was to blame, but his friend is reluctant to get another.

“It’s also said the virus keeps mutating,” Li said. “How do we know if the vaccines we take are useful?”

Some are reluctant because they have diabetes, heart problems and other health complications, despite warnings from experts that it is even more urgent for them to be vaccinated because the risks of COVID-19 are more serious than potential vaccine side effects in almost everyone.

A 76-year-old man taking his daily walk around the Temple of Heaven with the aid of a stick said he wants to be vaccinated but has diabetes and high blood pressure. The man, who would give only his surname, Fu, said he wears masks and tries to avoid crowds.

Older people also felt little urgency because low case numbers before the latest surge meant few faced risk of infection. That earlier lack of infections, however, left China with few people who have developed antibodies against the virus.

“Now, the families and relatives of the elderly people should make it clear to them that an infection can cause serious illness and even death,” said Jiang Shibo of the Fudan University medical school in Shanghai.

More than 90% of people in China have been vaccinated but only about two-thirds of those over 80, according to the National Health Commission. According to its 2020 census, China has 191 million people aged 65 and over — a group that, on its own, would be the eighth most populous country, ahead of Bangladesh.

“Coverage rates for people aged over 80 still need to be improved,” the Shanghai news outlet The Paper said. “The elderly are at high risk.”

Du Ming’s son arranged to have the 100-year-old vaccinated, according to his caretaker, Li Zhuqing, who was pushing a face-mask-clad Du through a park in a wheelchair. Li agreed with that approach because none of the family members have been infected, which means they’d be more likely to bring the disease home to Du if they were exposed.

Health officials declined requests by reporters to visit vaccination centers. Two who briefly entered centers were ordered to leave when employees found out who they were.