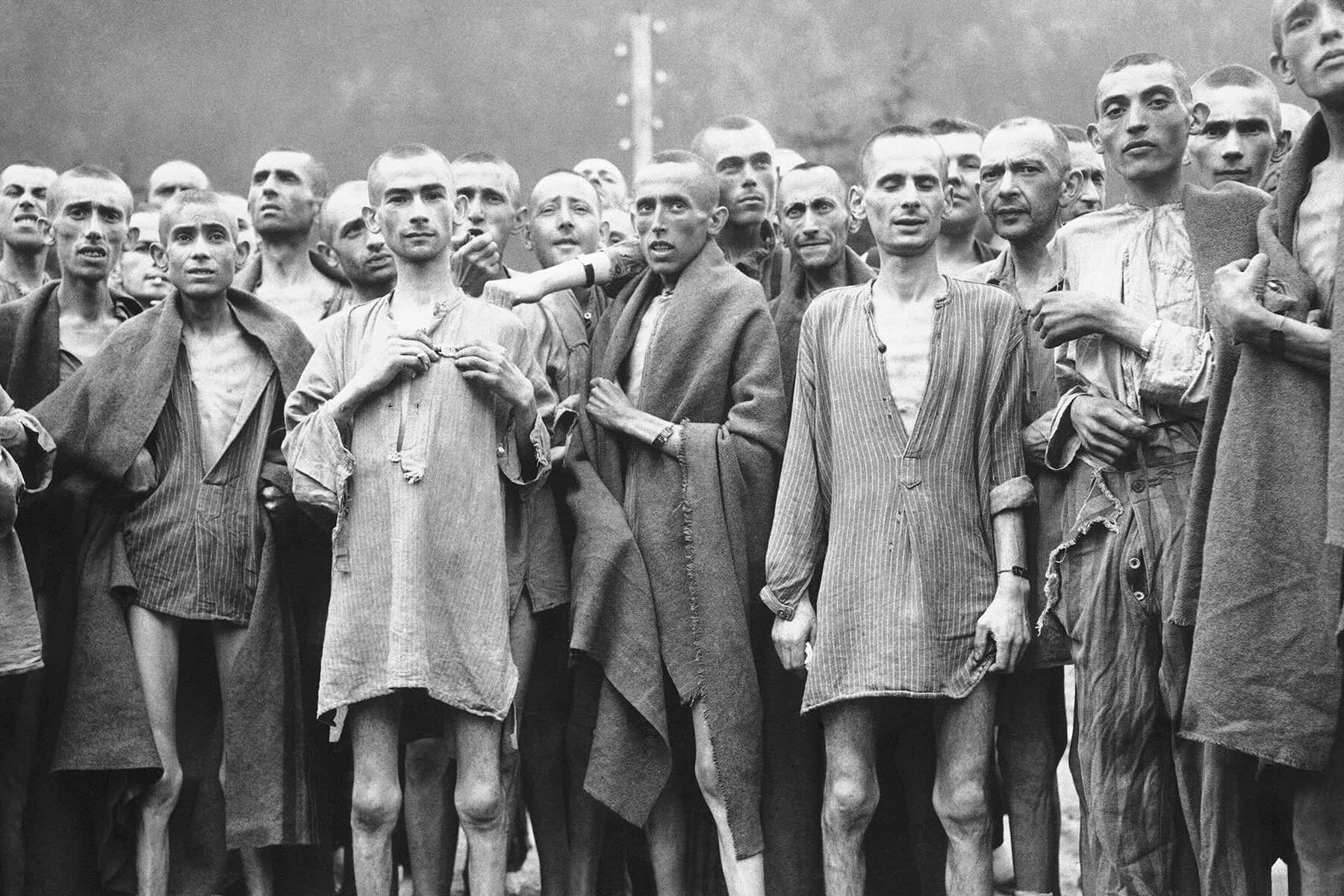

In the aftermath of World War II and the murder by Nazi Germany of 6 million Jews in the Holocaust, the world united around a now-familiar pledge: Never again.

A key part of that lofty aspiration was the drafting of a convention that codified and committed nations to prevent and punish a new crime, sometimes called the crime of crimes: genocide.

The convention was drawn up in 1948, the year of Israel’s creation as a Jewish state. Now that country is being accused at the United Nations’ highest court of committing the very crime so deeply woven into its national identity.

The reason the genocide convention exists “is related directly to what the (Nazi) Third Reich attempted to do in eliminating a people, the Jewish people, not only of Germany, but of Eastern Europe, of Russia,” said Mary Ellen O’Connell, a professor of law and international peace studies at Notre Dame University’s Kroc Institute.

In response to Israel’s devastating military offensive in Gaza that was triggered by murders and atrocities perpetrated by Hamas militants on October 7, South Africa has gone to the International Court of Justice and accused Israel of genocide. Israel rejects the claim and accuses Pretoria of providing political cover for Hamas.

South Africa also asked the 17-judge panel to make nine urgent orders known as provisional measures. They are aimed at protecting civilians in Gaza while the court considers the legal arguments of both sides. First and foremost is for the court to order Israel to “immediately suspend its military operations in and against Gaza.”

On January 26, The United Nations’ top court ordered Israel to do all it can to prevent death, destruction, and any acts of genocide in its military offensive in Gaza, but stopped short of ordering a cease-fire.

While the ruling stopped short of South Africa’s request for a cease-fire, it nonetheless amounted to a rebuke of Israel’s wartime conduct.

In the highly anticipated decision, the International Court of Justice decided not to throw out the case, and ordered six so-called provisional measures to protect Palestinians in Gaza. Many of the measures were approved by an overwhelming majority of the judges. An Israeli judge voted in favor of two of the six.

“The court is acutely aware of the extent of the human tragedy that is unfolding in the region and is deeply concerned about the continuing loss of life and human suffering,” Joan E. Donoghue, the court’s president, said.

Provisional measures by the World Court are legally binding, but it is not clear if Israel will comply with them. The January 26 decision is only an interim one. It could take years for the court to consider the merits of the genocide accusation by South Africa.

The death toll from the Israel-Hamas war in the Gaza Strip surpassed 26,000 on January 26, with more than 64,400 wounded since October 7.

WHAT IS GENOCIDE?

The 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, defines the crime as acts “committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such.” It lists the acts as killing; causing serious bodily or mental harm; deliberately inflicting conditions of life calculated to bring about the group’s physical destruction in whole or in part; imposing measures intended to prevent births; and forcibly transferring children.

The text is repeated in the Rome Statute, the founding treaty of the International Criminal Court, as one of the crimes under its jurisdiction, along with war crimes, crimes against humanity and the crime of aggression. The ICC prosecutes individuals and is separate to the International Court of Justice, which rules in disputes between nations.

In its written filings and at a public hearing in early January, South Africa alleged genocidal acts by Israel forces including killing Palestinians in Gaza, causing serious mental and bodily harm, and deliberately inflicting conditions meant to “bring about their physical destruction as a group.”

Israel has vehemently taken issue with South Africa’s claims, arguing that it is acting in self-defense against what it calls the genocidal threat to its existence posed by Hamas.

HOW DO YOU PROVE GENOCIDE?

As well as establishing one or more of the underlying crimes listed in the convention, the key element of genocide is intent — the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group. It is tough to prove.

“The most important thing is that whatever happens is done with the specific intent to destroy a group, so there’s no plausible alternative reason why those crimes have been committed,” said Marieke de Hoon, an associate professor of international law at the University of Amsterdam.

Said O’Connell: “Can you show that the widespread killing of these people was intended by the government? Or … was the government waging a war and during that war large numbers of this particular group died, but that was not the intent of the government?”

At public hearings in early January and in its detailed written submission to the ICJ, South Africa cited comments by Israeli officials that it claimed demonstrate intent.

Malcolm Shaw, an international law expert on Israel’s legal team, called the comments South Africa highlighted “random quotes not in conformity with government policy.”

HAS THE ICJ EVER RULED BEFORE ON GENOCIDE?

In 2007, the court ruled that Serbia “violated the obligation to prevent genocide” in the 1995 Srebrenica massacre, when Bosnian Serb forces rounded up and murdered some 8,000 mostly Muslim men and boys in the Bosnian region.

Two other genocide cases are currently on the court’s docket. Ukraine filed a case shortly after Russia’s invasion nearly two years ago that accuses Moscow of launching the military operation based on trumped-up claims of genocide and that Russia was planning acts of genocide in Ukraine. In that case, the court ordered Russia to halt its invasion, an order that Russia flouted.

Another case involves Gambia, on behalf of Muslim nations, accusing Myanmar of genocide against the Rohingya Muslim minority. Gambia filed the case on behalf of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation.

Both Gambia and South Africa have filed ICJ cases in conflicts they are not directly involved in. That was because the genocide convention includes a clause that allows individual states — even uninvolved ones — to call on the United Nations to take action to prevent or suppress acts of genocide.

HAVE OTHER INTERNATIONAL COURTS PROSECUTED GENOCIDE?

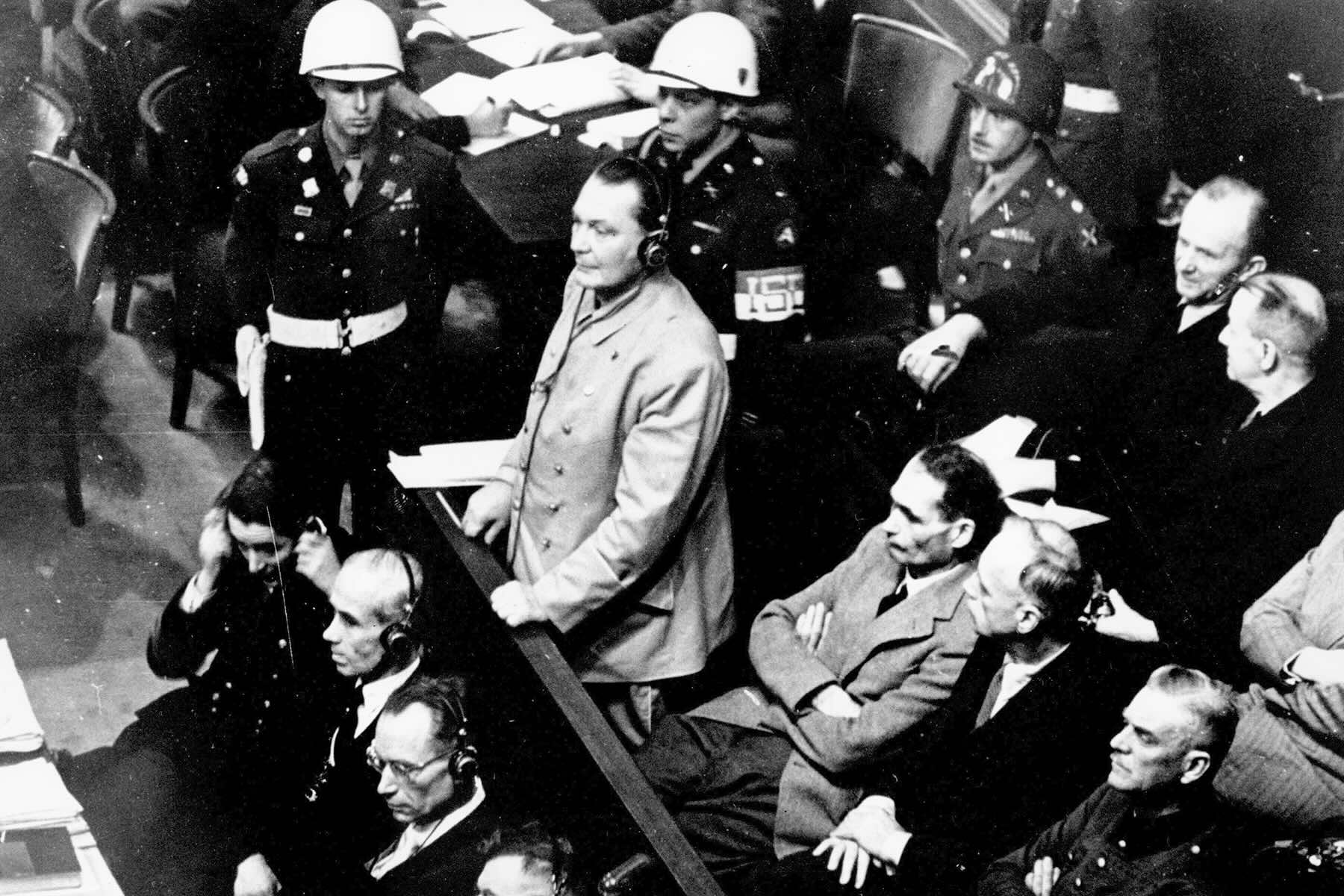

Two now defunct U.N. tribunals — for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda — both dealt with genocide, among other crimes. The Yugoslav court convicted defendants including former Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic and his military chief Gen. Ratko Mladic on genocide charges for their involvement in the Srebrenica massacre.

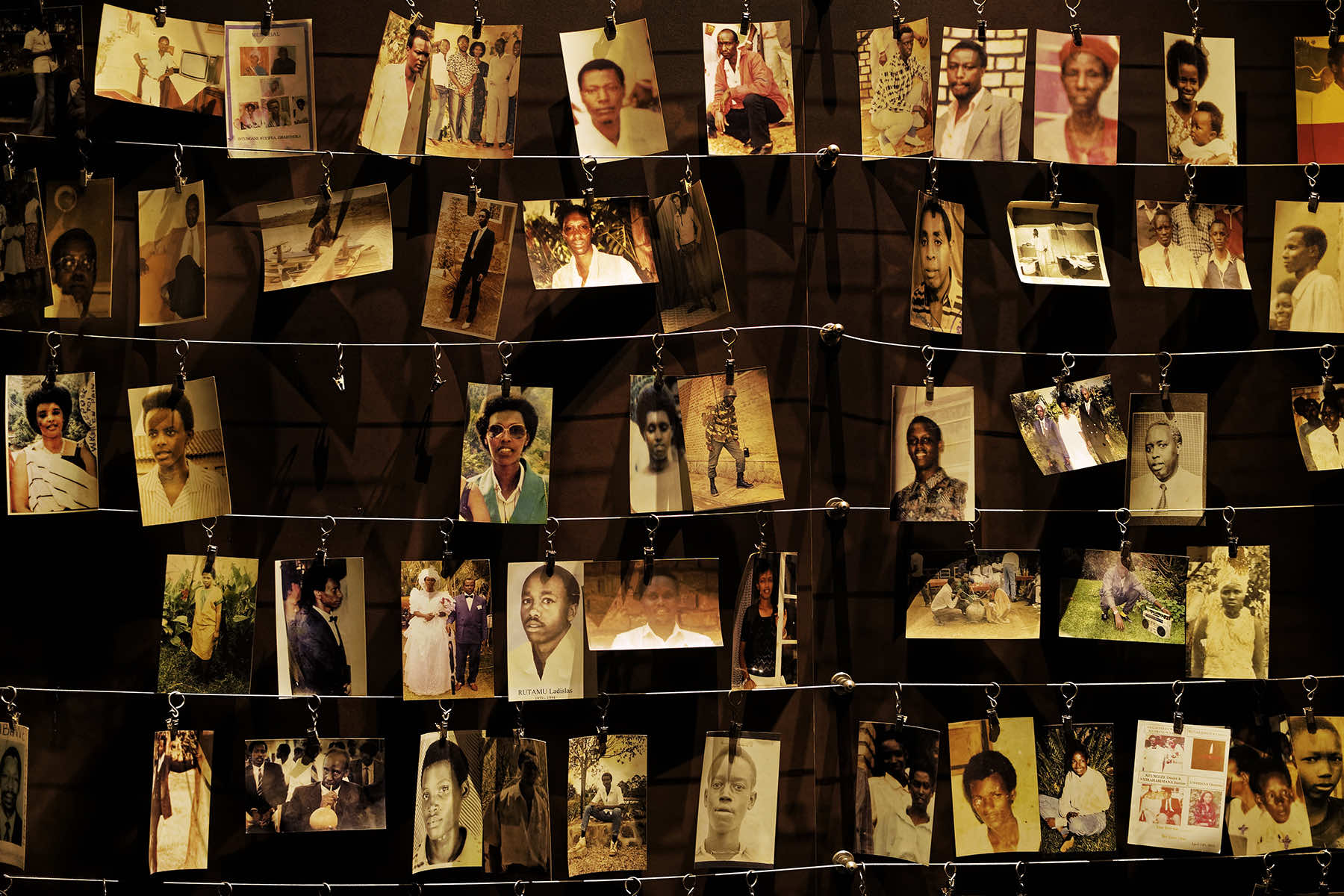

The Rwanda tribunal, headquartered in Arusha, Tanzania, was the first international court to hand down a genocide conviction when it found Jean Paul Akayesu guilty of genocide and other crimes and sentenced him to life imprisonment in 1998. He was convicted for his role in Rwanda’s 1994 genocide, when militants from the Hutu majority slaughtered some 800,000 people, mostly minority Tutsis. The tribunal convicted 62 defendants for their roles in the genocide.

The International Criminal Court has charged ousted Sudanese leader Omar al-Bashir with genocide in the Darfur region. He has not been handed to the court to stand trial. Al-Bashir’s government responded to a 2003 insurgency with a campaign of aerial bombings and unleashed militias known as Janjaweed, who are accused of mass killings and rapes. Up to 300,000 people were killed and 2.7 million were driven from their homes.

A hybrid domestic and international court in Cambodia convicted three men members of the Khmer Rouge whose brutal 1970s rule caused the deaths of an estimated 1.7 million people. Two of them were found guilty of genocide.

Mike Corder, Raf Casert, and MI Staff

Associated Press

THE HAGUE, Netherlands

Sebastian Scheiner (AP), Ben Curtis (AP), David Longstreath (AP), Stanislaw Mucha (AP), Zoltan Balogh (AP), Ahmed Alarini (AP), Mohammed Dahman (AP), Fatima Shbair (AP), Patrick Post (AP), and Anna Bohdan, David Peinado Romero, Drop of Light, Keith Brooks, Matthew Thomas Lock, Milano PE (via Shutterstock)