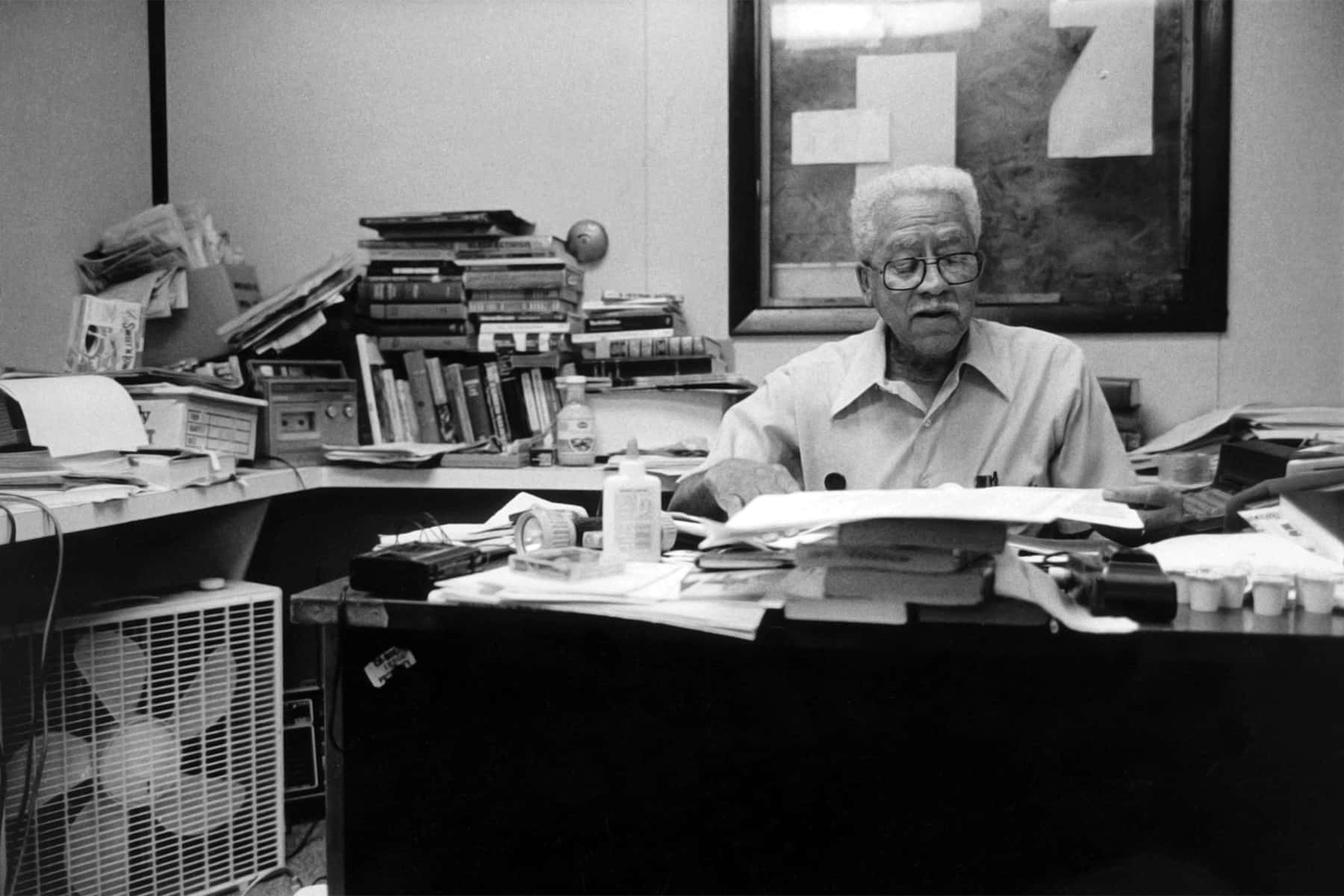

On a cloudy and overcast day in 1994, I was driving down North Avenue and saw something that caught my attention. It was a museum with an unusual name, America’s Black Holocaust Museum. I had only been back in Milwaukee for a little over a year after leaving California, which had been my home for most of the previous nine years. I parked my car on Fourth Street and walked up to the door of the museum.

I had no idea what to expect, and didn’t even know if it was open. An elderly man who introduced himself as James Cameron greeted me at the door. He welcomed me into his museum and told me to make myself comfortable. When I began to look around at the images on display it was unsettling. There were images around the space on foam board of men who had been lynched.

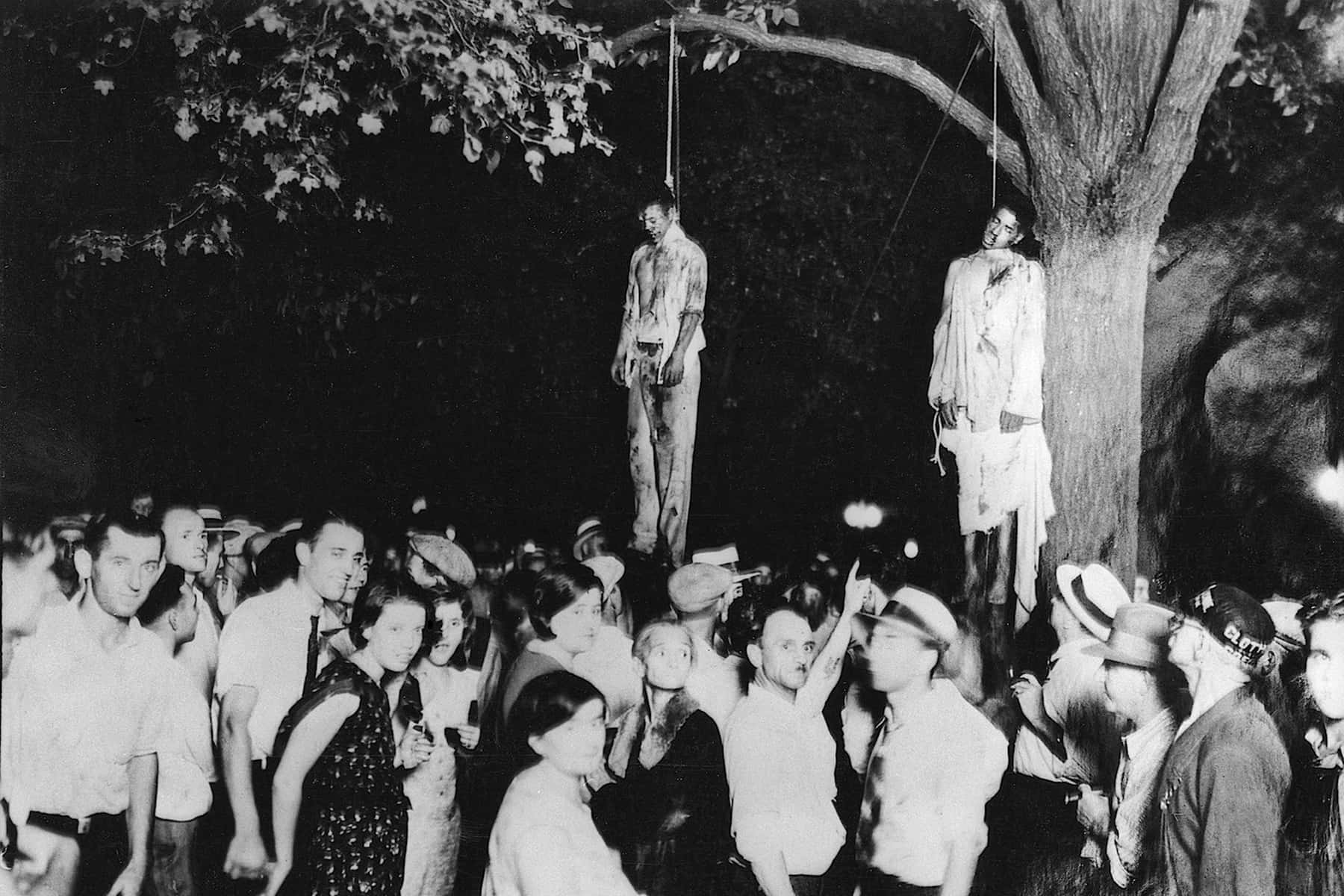

I was familiar with the ritual of lynching from my independent study of American history in places like my home state of Mississippi. I did not recognize many of the images he had in his museum. There was one that was larger and more prominent than the others. That particularly gruesome image, showed two young black males, Abrahm Smith and Thomas Shipp, hanging from a lyncher’s rope, side by side above a large crowd of white people. I immediately noticed the faces of the members of the crowd standing in the foreground of the image. Many of them were smiling. Some looked up at the bodies of the two young men who appeared to have suffered a terrible beating prior to being killed.

Mr. Cameron stood and watched as I walked round the museum looking at other lynching images and artifacts he had collected. Eventually he came over and told me the most unbelievable story I had ever heard in my life. He said the two boys hanging in that first lynching image were his friends Abe and Tommy. I was taken aback and told him I was sorry that he had lost two friends that way. Little did I know that the story of the lynching would go much deeper.

As I sat on a metal folding chair, he began to tell me about that night. It was August 7, 1930 in Marion, Indiana. This small town in North Central Indiana had been his hometown. He asked me my name and said “Reggie, I was supposed to be hanging next to my friends on that tree.” This was the beginning of a four-hour trip to America’s Black Holocaust Museum that would eventually lead to a relationship that has lasted nearly seventeen years.

I had no idea that the visit would change my life. About eight years later I visited the museum again with intentions of volunteering to help Mr. Cameron. The museum looked much different that warm June day in the summer of 2002. It was bigger, and the entrance was in a different place on the building. Two people greeted me this time. One was Gerald Wallace, a former actor and theater owner. He was gregarious and the type of person that you knew right away you would either love or hate. I grew to love him as a friend and colleague. A beautiful woman with a gentle whisper of a voice named Jeannette Bryant told me to not pay any attention to Mr. Wallace as she grabbed my arm and walked me into the museum’s exhibit space.

Mrs. Bryant, as I would grow to know her as, was what she called the Head Griot of the museum. I had never heard the word griot before. She said the receptionist told her I wanted to volunteer. I said, “Yes, what can I do to help?” She said, “You can become a griot.” I asked her what that meant. She said, we are the people who give tours to our guests. We honor our West African traditional keepers of the history.

Griots are some of the most revered members of West African communities. The museum uses that term to describe its docents. All the while as I was driving over to the museum I thought I would help sweep up or organize things in the museum, and help Mr. Cameron with whatever needs he had. I wondered that day but did not ask where he was.

By the end of the day I would see the new version of the museum and learn a lot about the mission of the museum. I was off work on what my job at a local chemical company called voluntary time-off. The economy downturn had led the company to suffer financially and they offered anyone with interest up to five weeks of voluntary time off. I took advantage of the break from work for the next five weeks by volunteering at the museum each day it was open.

I would go through training by Mr. Wallace and Mrs. Bryant as well as shadowing them when they gave tours. By the end of the week they threw me to the wolves by saying “You’re on your own young man.” I had an advantage that many did not have, because I knew much of black history from my lifetime of studying of history. I began to give tours that were probably not great that first couple of weeks. I had to remember a lot of details about Mr. Cameron, the Transatlantic Slave Trade, the enslavement of African captives all over the United States, and many other things. Eventually, I became the Head Griot when Mrs. Bryant left the museum. It is a title that I have held for nearly sixteen years and take great pride in.

Then one day I saw Mr. Cameron, as he visited his office in the museum. He did not remember me on that day, but in time we became close friends and he became my mentor. I grew to love him like a father. He treated me like a son. I spent many hours that summer speaking with him at the museum and would visit him at his home regularly over what would be the last four years of his life.

By the time I came back to volunteer at the museum, everyone was calling him Dr. Cameron. I learned that he had received an honorary PhD from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee for his lifetime of work as a civil rights pioneer. Dr. Cameron was the most interesting person I had ever known. The four years I spent building a relationship with him changed the course of my life.

This gentle soul had a tremendous influence on everyone he met. He was full of love and had a great sense of humor. Dr. Cameron was a unique person. He was possibly the only living survivor of a lynching. We know he was the only one who wrote about the experience of surviving a lynching. Today would have been his 105th birthday. He was born in La Crosse, Wisconsin in 1914 but would spend his teen years primarily in Indiana.

He was a happy child with many close friends and did really well in school. I would tell people he was a walking encyclopedia because of his photographic memory and vast knowledge of so many different topics.

As a sixteen-year old, sweltering from a really hot summer in Marion, his life would change on August 6, 1930. On that day, his good friend Abe Smith and an associate, Tommy Shipp, picked him up in Tommy’s car.

As they drove away they told “Jimmy,” as he was known then, that they planned to go down to the Lover’s Lane area outside of town to stick up someone. Being two years younger than Abe and three years younger than Tommy, he succumbed to peer pressure. As they drove toward the area, they gave him a revolver and told him to “not be a chicken.”

“Just open the door and say stick-em up” they told Jimmy. He reluctantly did so. As he approached the car parked alone next to the river, he was shaking like a leaf. When he opened the door, he recognized his friend, a young white fella named Claude Deter. He was in the car with his girlfriend, Mary Ball.

Cameron gave the gun back to Abe and Tommy and ran away as fast as he could. He would eventually hear gunshots. He told me about that fateful day as if he had told the story a million times. Among the numerous other lynching photos in the museum, this story was personal. There was also the image of Mack Charles Parker who was lynched in Mississippi. He had been falsely accused of raping a pregnant white woman in Pearl River County in February of 1959. Three days before his trial was set to start, a mob kidnapped him from his jail cell with the assistance of a deputy sheriff. Parker was beaten and dragged down the street by the group of eight to ten masked men.

The men stopped at the Louisiana border on a bridge above the Pearl River. They had planned to castrate Parker, as was common practice in these types of lynchings. The mob also wanted to leave his body hanging from the bridge much like Abe and Tommy were left dangling for the crowd to see. Instead, they shot him in the chest two times from close range and he died within a few seconds. His body was weighed down with a logging chain and tossed into the river, reminiscent of 14-year old Emmett Till who was killed in a similar way near my hometown in Mississippi four years earlier. His body rose to the surface and was found by those searching for him after he was abducted.

The image of Mack Charles Parker’s body is one of the ugly reminders we have of the murder of blacks across the country by mobs of whites who felt empowered to take the law into their own hands. This lynching image was one of the many in the museum. As was the normal course of events in lynchings, the lynchers would never be held accountable. Several of them confessed their roles in the lynching of Parker to the FBI but would never be tried for his murder. Both the judge and prosecutor refused to cooperate with the FBI investigation. Two grand juries were called, one state and one federal, each failed to indict the murderers of Parker. They lived out their lives as free men until the day they died.

As Abe and Tommy were shooting Claude Deeter, Jimmy Cameron was running to his home. When he arrived, sweating profusely, his mother asked what he had been doing. He lied and said he had been playing football with friends. After the shooting, a farmer from across the road took Deeter to a local doctor for treatment. Twenty-three year old Claude Deeter died later that night after identifying Smith, Shipp, and Cameron.

A rumor began to spread that Mary Ball had been raped, which was not true. It did not matter. In the United States of 1930, a black male accused of raping a white woman was pretty much guaranteed to die. His death would take place after a short “trial” in the regular court system or at “the hands of persons unknown,” as the medical examiner would generally rule after a lynching took place. It did not matter that the murderers were identified, they would not be held accountable for the lynching of a black person.

Cameron told me of hearing the crowd chanting, “we want Cameron, we want Cameron” after murdering Abe and Tommy. The local Sheriff had arrested the three late that night. A crowd of between ten and fifteen thousand angry whites looking for vengeance had gathered around the Grant County Jail, intent on getting those “boys.” The Sheriff told his deputies not to fire into the crowd because women and children were present. Many of these “spectacle” lynchings took place across the country from the early 1880s through the 1930s. Large crowds gathered from neighboring communities to bear witness to the lynching of black men, women, and children.

Freight trains would sometimes be sent out to transport people to the scene of the lynching and newspapers would announce the time and place ahead of time. Entrepreneurs would sell sandwiches and drinks to the members of the crowd. Torture and mutilation of the victims preceded their actual murders in most cases. Some would be shot, some hanged, some burned alive. Souvenirs such as clothing from the lynching victims, their body parts, pieces of the lynching rope and even bark from the tree would be the most sought after prizes. Photographs of the lynching would be very popular as well. Many of these photos would be placed on postcards and sent through the U.S. Mail.

In Marion, on a hot ninety-nine degree day, thousands of whites gathered around the jail demanding that the Sheriff release the three young boys they intended to murder. He refused to open the jail to the mob. They spent hours breaking the bricks around the large metal door of the jail with sledgehammers and crowbars. Finally, they succeeded and gained entrance to the jail. They would beat Abe and Tommy unmercifully before killing each of them.

A local professional photographer, Lawrence Beitler, would be hired to photograph the scene. He took several photos of the bodies of Abe and Tommy hanging in the courthouse square with a festive crowd cheering him on. He set up lights and had branches cut off of the tree to get the best possible photograph. One of the many that he snapped would become iconic. The photo of the lynching in Marion would go viral. He probably sold thousands of copies and the image would be shown in newspapers around the world.

Abel Meeropol, a poet and songwriter would see the image years later and write a poem he called “Bitter Fruit” in 1937. The thirty-four year old son of Russian Jewish Immigrants eventually converted the poem into a song, Strange Fruit. Billy Holiday was the first to record the song in 1939. The lyrics refer to “black bodies hanging from the poplar trees” which are commonly found in the South. This means Meeropol thought the image from Marion, Indiana was a lynching in the South even though it was in the North.

As Mr. Cameron recounted the story to me on that first visit, I was amazed at how someone could re-tell these events without being traumatized all over again. He says the mob entered his cell and dragged him out, beating him along the way. He saw the faces of many people he recognized in the crowd. Those who punched and kicked and spat at him were some he considered to be friends.

All of the black residents of Marion had fled the city to find safety in Weaver, Indiana. The enraged mob was not content with having simply killed the first two. They had tortured and killed both Abe and Tommy. Tommy had been castrated and covered with a Ku Klux Klan robe. In the photograph you can see that the clothing over his body was different. Years later a young student visiting the museum would ask me why he had on those strange clothes.

Many years after the lynching, Mr. Cameron would marry the love of his life, a young woman named Virginia. She was a great wife and mother to the five children they raised together. I would spend many hours at their home on Teutonia Avenue. She would prepare meals on most days when I came by. We would laugh together and I loved the way they finished each other’s sentences and made fun of each other. Mr. Cameron was eighty-eight years old by the time I began to get to know him well. He told me about his life and the trials and tribulations of working for civil rights in Indiana, the state that had more Ku Klux Klan members than any other in the 1920s and 1930s. I remember him talking about his struggles to open up chapters of the N.A.A.C.P. in Indiana. He would be appointed Director of Civil Liberties in Indiana years after the lynching.

As this sixteen year old approached his moment of death, he was beaten and dragged through the crowd. He finally saw the hanging bodies of Abe and Tommy. He said a prayer and asked God to forgive him for his sins. As he waited to be killed, he heard a soft voice. He would say it was the voice of an angel sent by God.

“Leave this young man alone. He had nothing to do with these crimes” the voice said to the mob of angry whites. Miraculously, they let him go and he stumbled back to the jail.

He would eventually write the story of this miracle. His memoirs, “A Time of Terror: A Survivors Story” is currently in its third edition. He sold me a copy of the original edition during my first visit to the museum. He had tried for decades to get someone to publish the book. Finally in 1982, he took out a second mortgage on his home and published it himself. Black Classic Press published the second edition. The third edition was published in 2016, and I wrote the Afterword for it.

It would take a year before young Cameron would face the charge of being an accessory before the act of manslaughter in an Indiana courtroom. Mary Ball testified that she had never been sexually assaulted. Seventeen year old Cameron, despite the best efforts of his attorneys, was found guilty and sentenced to four-to-twenty-one years in the same adult prison that famous gangster John Dillinger had once occupied. He would be paroled after five years of imprisonment, one year in jail awaiting trial and four years in prison. During this time he began to write the story of the lynching. The authorities would confiscate his writings prior to his release from prison. He was forced to leave the state of Indiana but eventually came back and interviewed witnesses of the lynching for his book.

In 1952 he moved his family to Milwaukee and made it his home until he passed on June 11, 2006. I was fortunate enough to become good friends with this amazing man. I studied under him as he shared many books and resources that he had studied during his life. He, much like myself, loved books. Dr. Cameron trusted me to take on the work that he started in 1988.

I have done all that I can to keep his memory alive and to build on his original America’s Black Holocaust Museum. We launched a virtual museum on his birthday in 2012 at abhmuseum.org. Over five million people have visited the virtual museum in the past year from over two hundred countries.

During a trip with his church to the Holy Land in 1979, he and Virginia visited Yad Vashem, the Jewish Holocaust Memorial. While standing in the Garden of the Righteous Gentiles, dedicated to non-Jews who had risked their lives helping Jews escape the Holocaust in Europe, he had an epiphany. He turned to Virginia and said “We need a museum like this in America which tells the stories of the sufferings of blacks and those freedom loving whites who have assisted us in the country.” That became the genesis of the museum he would open nine years later at the age of seventy-four.

This incredible man who had escaped a lynching at the age of sixteen became the most loving person I have ever met. He loved people, he loved his country, he loved bringing this hidden history of the sufferings of blacks alive. His goal was to provide a platform to begin the healing process.

America has suffered for four hundred years under a veil. This veil has hidden from all of us the harsh realities of racism against Africans and their children and grandchildren. None of us have been taught the reality of how race-based laws and policies for all of the nation’s history have kept black people in a condition of wretchedness, simply because of the color of their skin. It is a badge of dishonor that we cannot escape. Our pigmentation marks us as an “other” in America.

We cannot bleach our skin or change our names to escape this degradation of being at the bottom of the “racial” hierarchy of America. We have suffered but we have been the most resilient people America has ever known. We have been fighting for dignity, justice, fairness, and basic human decency since the first Africans arrived on a slaving ship in 1619. Our presence in America has helped to make it the Super Power nation it is today. The wealth of America came on the backs of Africans working tirelessly under the threat of violence with no compensation.

Dr. Cameron believed as I believe, that America cannot live up to the ideals of the Founding Fathers unless it becomes a more honest nation. A nation that is willing to bear its soul to the world and admit that its treatment of black people has been – and in many respects – continues to be horrible. Learning the hidden history of America’s treatment of black people enriches us all and leads us to understand and empathize with their plight. It allows us to let go of the guilt about discussing race and racism.

Unless we can be honest and use this history to be a better country, we will continue to suffer and continue to traumatize millions. We can, and should, and must do better. That day in 1994 put me on the path to work toward educating others. I have been on a mission to live up to the high standards set by Dr. Cameron. I have been a part of a small army of dedicated volunteers who have built enough momentum that America’s Black Holocaust Museum is being reborn in a new physical space on the footprint of the former museum, nearly nine years after closing in 2008.

My hope is that this new museum gets the financial support it deserves, unlike the previous museum. We cannot afford to lose this important memorial museum. It is one of a kind. Dr. Cameron was the first to tell the story of blacks in America as a holocaust.

This miracle of its rebirth, like the story of the Phoenix in Greek mythology, is one that we must thank Dr. Cameron for. Although he is not with us in the physical world, he lives in all of us that continue his important work. The new museum space would not be happening without the courage and motivation he instilled in us.

Dr. Cameron lives in me and drives me to teach and write about our struggles with racism. I would not be who I am today without this wonderful man.

Happy Birthday, Dr. Cameron. I love you.