On November 19, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln delivered one of the best known speeches in American history, at the dedication of the Soldiers National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

This essay is part of a series of opinion pieces. Each one is no longer than 272 words, the length of Gettysburg Address, and responds with a view of how Lincoln’s spoken ideas in Gettysburg are relevant to America in 2017.

Lincoln’s Gettysburg address in 1863 recognized the promise but not reality of our new nation’s pledge of “Liberty,” based on “the proposition that all men are created equal.”

After a union victory, but still in the midst of an uncertain war that would claim the lives of 600,000 troops, Lincoln’s dedication concretely recognized the iconic words of his prophet Frederick Douglass: “If there is no struggle, there is no progress. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.” Only that military struggle ended the rebellion and slavery based on color.

Some seven score and 14 years later we see the promise of the Emancipation and the 13th Amendment overtaken by mass incarceration (over 2 million currently confined, and 70 million carrying criminal records with deep, often lifelong deprivations). As our recent “Confronting Mass Incarceration” series revealed: this is a unique and tragic experiment, limited to our one “exceptional” nation, and only the past 40 years. Beyond that, Wisconsin imprisons twice as many people as our neighbor Minnesota. We rank number one in the country in racial disparity (jailing Blacks at a rate 11.5 higher than whites compared to their population).

In 1911, as white supremacist rebels were being honored from the Jim Crow South to Princeton, the Milwaukee Turners erected a monument to our 26 members who gave their lives at Gettysburg and elsewhere to bring truth to the promises that Lincoln extolled. We demean their sacrifice if we fail to recognize and confront the fact that today we again have the promise but not the reality of Emancipation.

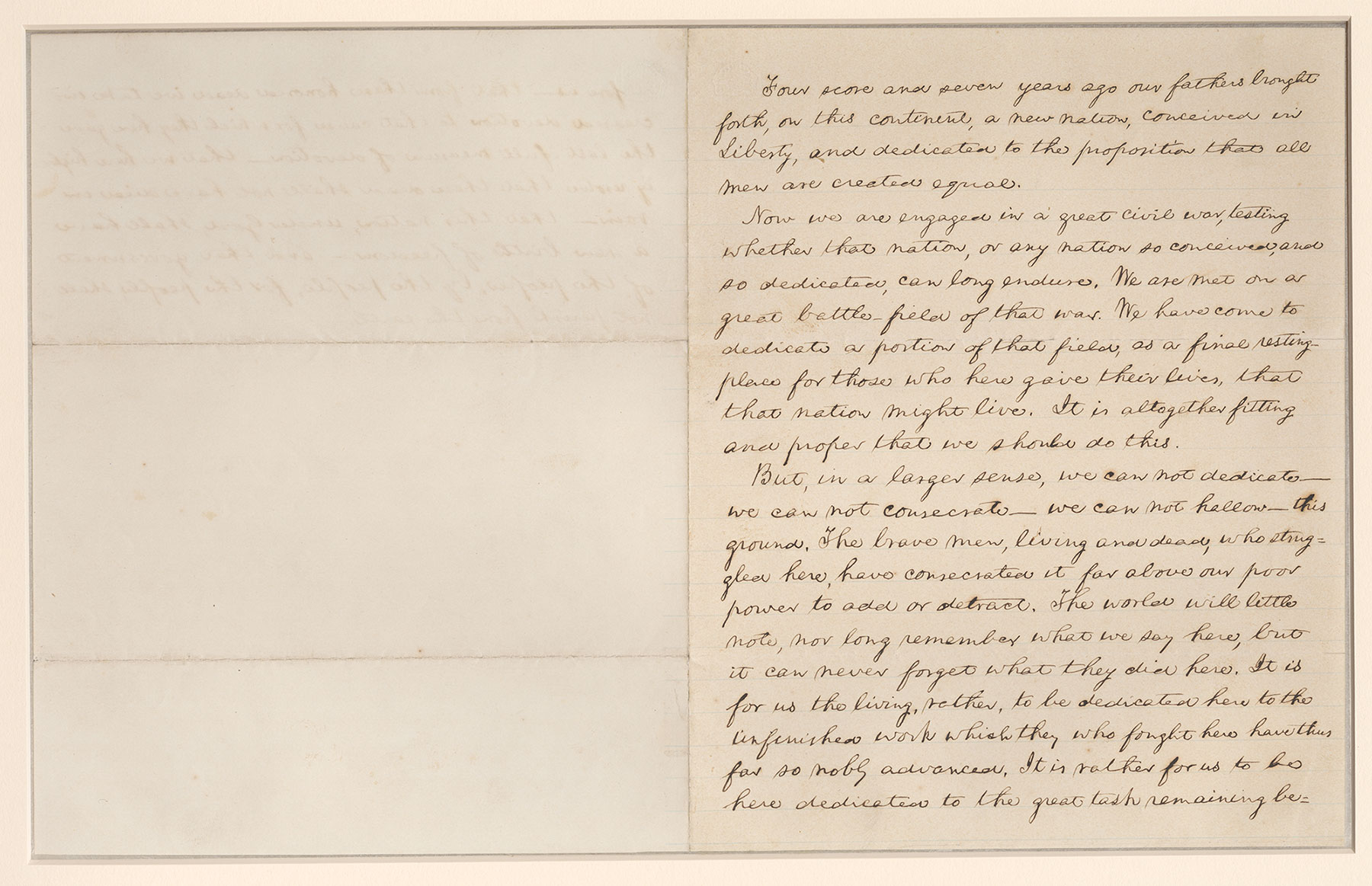

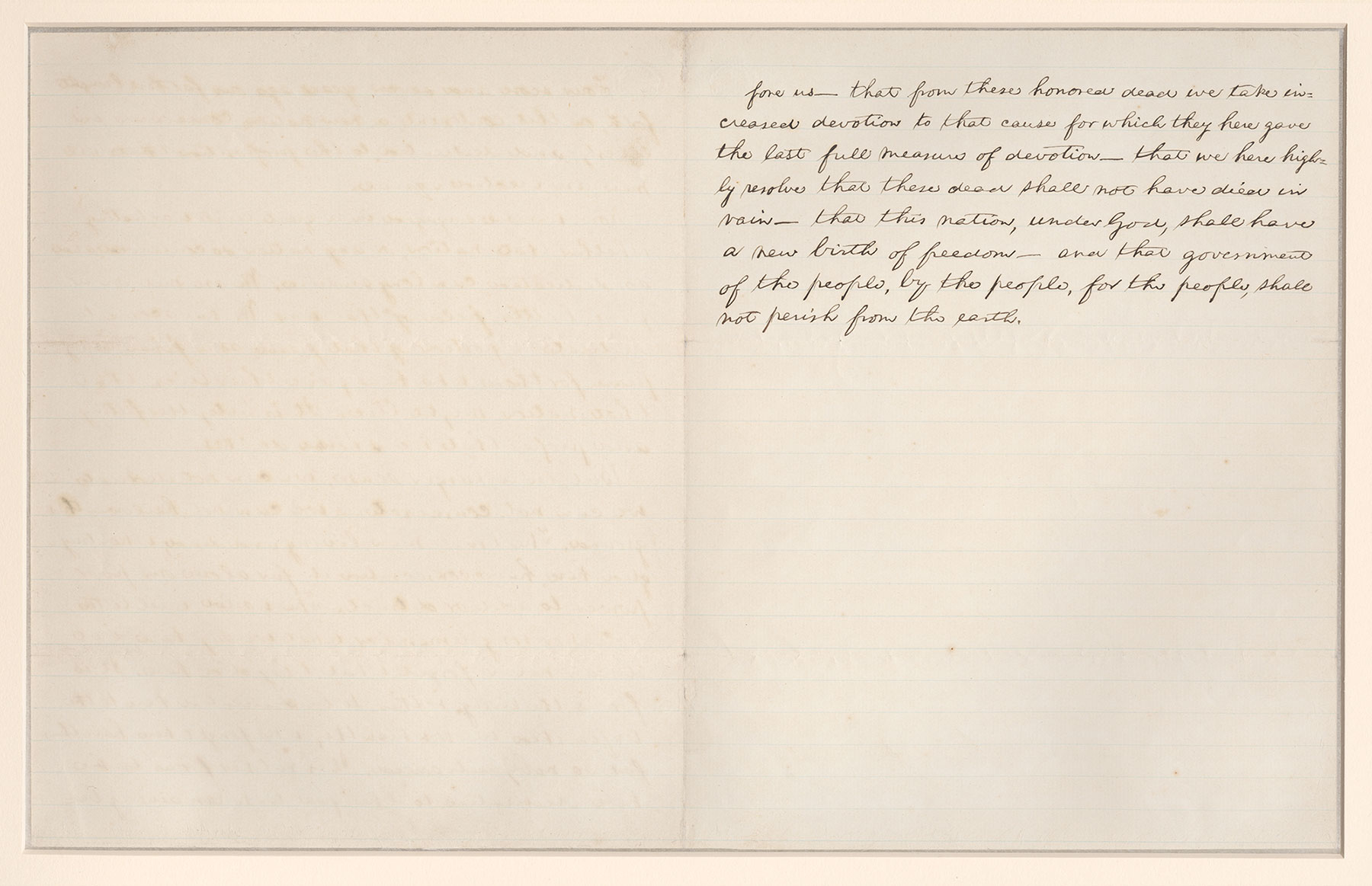

Lincoln's Gettysburg Address (The Bancroft Version)

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives, that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate, we can not hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they here gave the last full measure of devotion – that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Cornell University Library’s copy of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address is one of five known copies in Lincoln’s hand. Written out by President Lincoln at the request of U.S. historian, George Bancroft, this copy, the fourth that Lincoln composed, is known as the Bancroft Copy.

Art Heitzer is a local attorney and President of Milwaukee Turners, Inc.