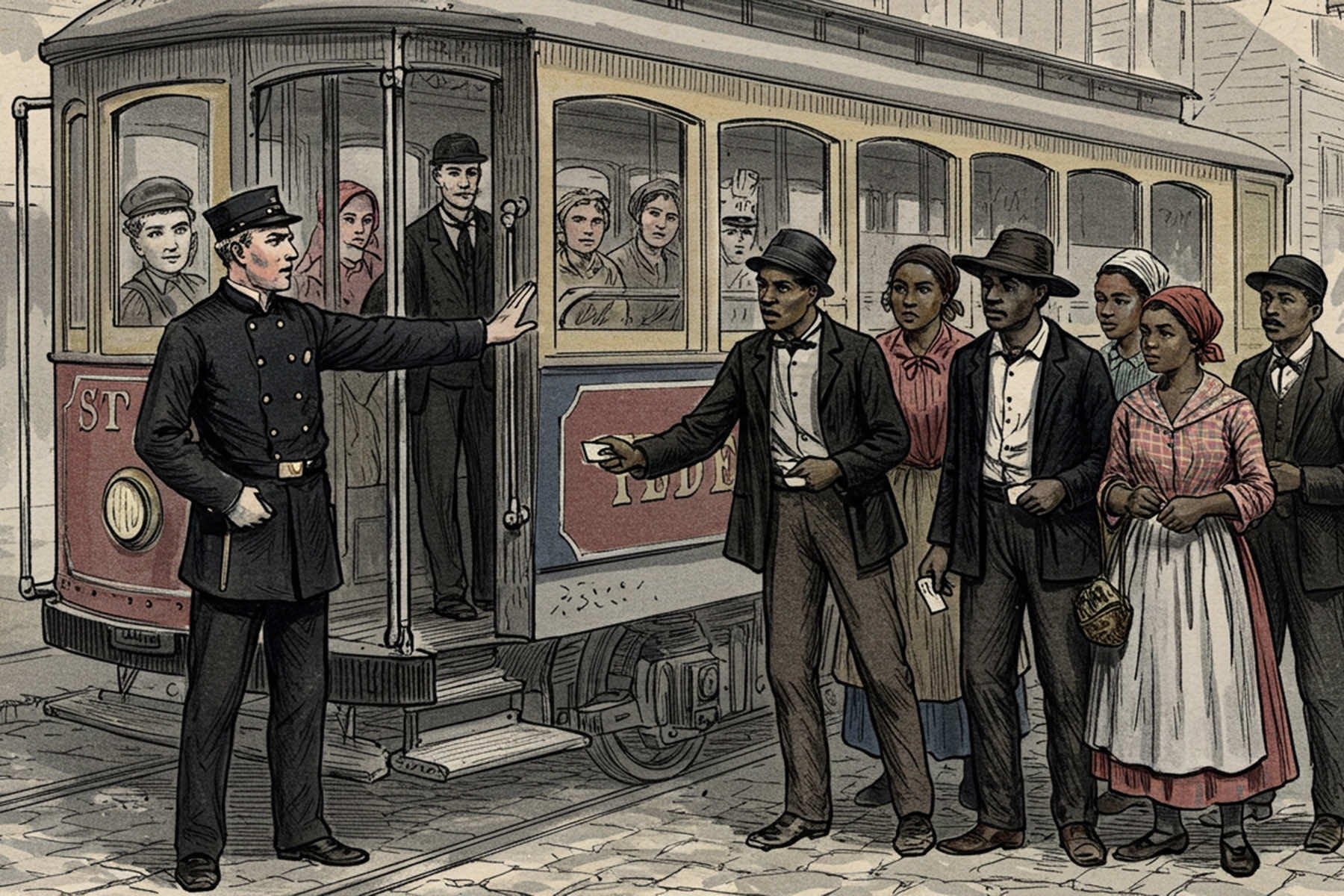

In the summer of 1896, African American communities across the United States mounted a broad and determined response to the Supreme Court’s ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson, handed down weeks earlier in May.

While the decision effectively legalized racial segregation under the doctrine of “separate but equal,” it also triggered the earliest wave of coordinated Black civic resistance following the end of Reconstruction.

Often overshadowed by later national civil rights efforts, the post-Plessy mobilizations that began in Northern cities such as Milwaukee, Chicago, and Boston represented a decisive turn toward organized protest against the consolidation of Jim Crow laws.

The responses came not only from Southern Black communities directly targeted by new segregation statutes, but also from urban centers in the North, where African Americans sought to block the spread of legalized racial separation through the press, church, and political channels.

In Milwaukee, the Black population remained relatively small at the time, estimated to be under 2,000, but it was already developing institutional footholds. Local churches, particularly African Methodist Episcopal and Baptist congregations, served as centers for civic discussion and social cohesion.

Though formal segregation laws were not on the books in Wisconsin, African American residents expressed concern that the Plessy decision would encourage discriminatory policies in housing, employment, and public accommodations, even outside the South.

Public meetings were held throughout the summer in Black church basements and rented halls. These gatherings focused on circulating information about the ruling, organizing local petitions, and strengthening community ties.

Records in local newspapers and church bulletins reflect a shared concern that the Supreme Court had signaled its willingness to accept racial hierarchy under constitutional law. Rather than isolating communities, the ruling prompted an early form of networked resistance.

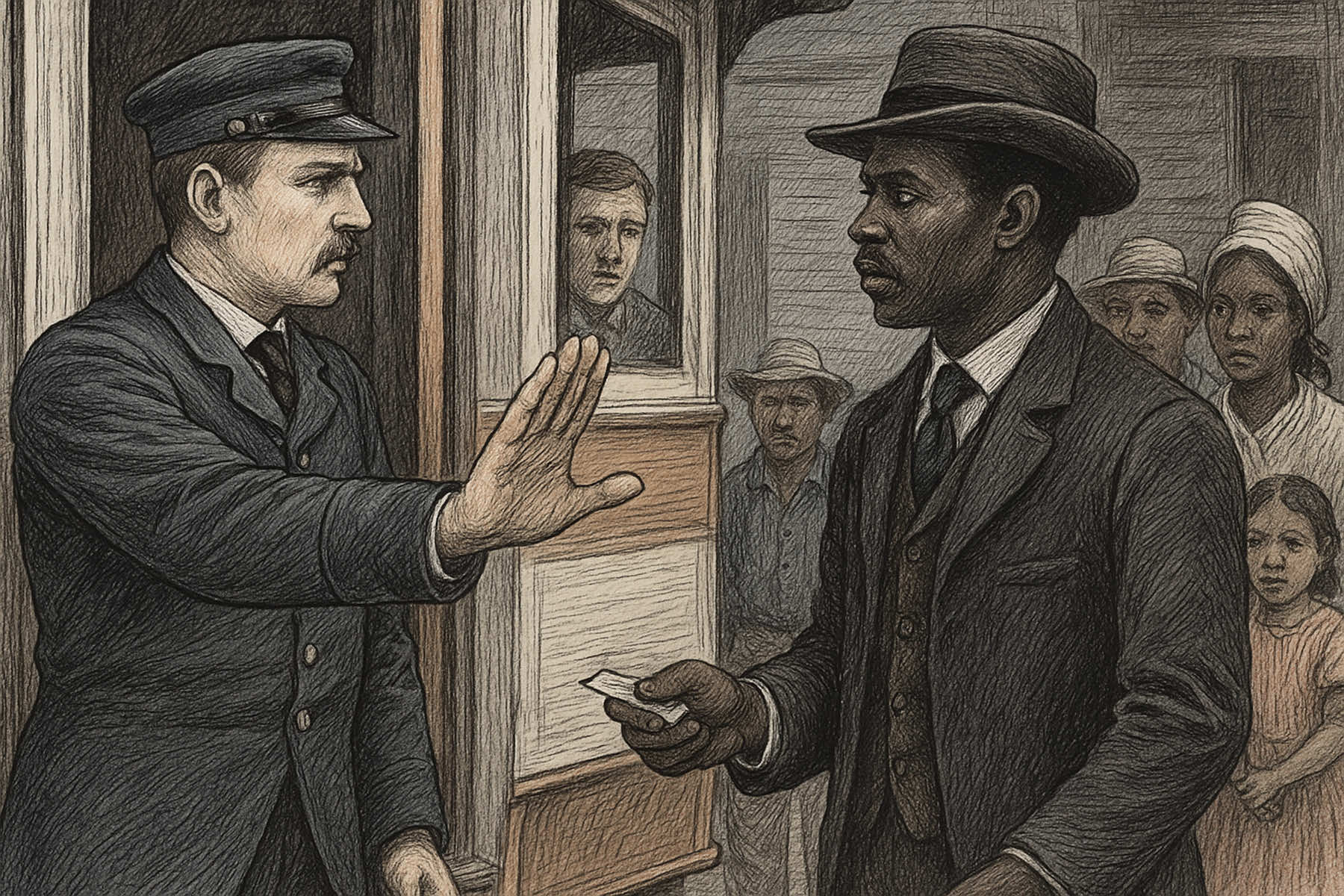

African American leaders in Northern cities used newspapers to frame the Plessy decision as part of a broader pattern of federal retreat from the civil rights gains made during Reconstruction. Many editorials drew connections between the ruling and the rollback of voting protections, the collapse of federal enforcement efforts, and the surge in race-based exclusion ordinances appearing in municipalities across the country.

In Milwaukee, African American residents engaged with local government to preempt any adoption of Southern-style segregation policies. Community discussions in the summer of 1896 centered on access to education and public services.

While explicit bans on Black attendance or presence were not in place, activists pointed to growing patterns of informal exclusion and advocated for local ordinances that would affirm equal use of public resources. Their efforts were part of a broader national response.

In Chicago, New York, and Boston, African American communities organized protest sermons, public resolutions, and legal appeals. Civic organizations, often formed around churches or educational societies, sought to challenge the ruling’s underlying premise through state-level litigation, public education campaigns, and political advocacy.

While they did not operate under a unified national leadership, many of these groups communicated through a loose network of Black-owned newspapers and denominational associations. The long-term impact of the summer actions would take years to become fully visible. The summer of 1896 was not a moment of complete defeat, but of rapid mobilization and strategic recalibration.

While the Plessy ruling itself remained intact until it was overturned in 1954 by Brown v. Board of Education, its immediate aftermath produced the first wave of sustained civic engagement by African American communities in the post-Reconstruction North.

In cities like Milwaukee, the response helped set patterns that would define Black political organizing in the decades to come. The strategies predated the national civil rights organizations that would later adopt similar models on a larger scale.

They included the use of churches as meeting spaces, publication of local bulletins and newsletters to disseminate information, and formation of neighborhood-based advocacy groups focused on local government accountability.

The Plessy decision also influenced how legal segregation evolved in Northern and Midwestern states. Although Wisconsin did not adopt formal segregation laws, local customs and policies gradually created de facto separation in schools, public housing, and employment.

The distinction between legal segregation in the South and social exclusion in the North blurred over time, as public systems became increasingly shaped by zoning rules, school district boundaries, and discriminatory lending practices.

Legal scholars have noted that Plessy’s affirmation of separate but equal provided a constitutional justification that was cited by state and local courts well into the 20th century.

Even when explicitly segregationist laws were absent, courts often refused to challenge exclusionary practices if they did not violate the letter of equal protection under the 14th Amendment. That legal precedent gave cover to many forms of indirect racial discrimination that became embedded in American institutions.

Milwaukee’s early efforts to resist segregation helped foster a culture of vigilance among its Black residents. Civic groups formed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries drew on the same networks established in 1896, including inter-church alliances and education committees.

Those groups played key roles in later fights against housing discrimination and in supporting legal challenges to school segregation and public employment exclusions in the mid-1900s.

The political legacy of Plessy also extended into national electoral dynamics. As disenfranchisement laws swept through the South after 1896, Black voters increasingly looked to Northern cities to exert influence, especially in local and state races.

Milwaukee’s Black population remained relatively small through the early 20th century but contributed to political shifts in city wards where turnout could affect council representation and public policy decisions.

In the post–World War II period, civil rights activism in Milwaukee accelerated, drawing in part on the same organizing structure that had first taken shape in response to Plessy. Groups like the Milwaukee United School Integration Committee (MUSIC) and the NAACP Youth Council adapted earlier strategies, while focusing on systemic inequality in public education and housing.

By the 1960s, Milwaukee had become a focal point for civil rights action in the North, particularly around issues of school desegregation and open housing. These campaigns were not spontaneous reactions but the product of an organizing culture that had roots in the 1890s.

The Plessy decision was the catalyst that first revealed the need for long-term legal and political infrastructure to combat racial discrimination, even in states where it was not codified by name.

Today, the structural effects of Plessy remain visible in debates over school funding, residential segregation, and voter access. Although the legal doctrine of “separate but equal” has been discredited, the systems it enabled continue to shape American political geography.

District maps, zoning rules, and administrative policies often produce outcomes that resemble segregation in practice, if not in law.

The July 1896 mobilizations were the first indication that Black Americans understood both the immediate and long-term threat posed by the Plessy ruling. Their response set a precedent for civil resistance strategies that would continue to evolve.

In cities like Milwaukee, these early efforts provided a lasting framework for political engagement that endures into the present.

© Art

Isaac Trevik