Fifty years after the fall of Saigon, the Vietnam War remains a defining rupture in American history. Not only in terms of foreign policy and military engagement, but in how it reshaped culture, identity, and public trust.

It was the first U.S. conflict to be fully televised, the last fought under conscription, and perhaps the most bitterly contested at home. As American troops fought a shadowy war abroad, an equally fierce cultural battle unfolded at home across radio airwaves, bookstore shelves, movie screens, and living room televisions.

This was a war that left no corner of American life untouched. Music and film raged against its violence or mourned its toll. Television, long silent on the subject, eventually found ways to confront it — sometimes through satire, sometimes through searing realism.

Books, both fiction and nonfiction, tried to make sense of what was happening in the jungles of Southeast Asia and in the hearts of those who served. Together, these media reflected public opinion and also helped shape it, fueling protest movements, reshaping the image of the soldier, and chronicling a collective national trauma that continues to evolve.

The works that emerged in response to the Vietnam War were not just reactions to geopolitics. They were acts of reckoning: with institutional failure, with personal loss, with cultural division. Many of them focused on the soldiers, their disillusionment, grief, and return to a country that often failed to welcome them.

Others widened the lens, depicting the war’s moral ambiguity, its racial injustices, or its effects on Vietnamese civilians — perspectives long excluded from the mainstream.

This list explores how the Vietnam War was interpreted, challenged, and immortalized across four forms of entertainment: films, television, songs, and books. They offer not just a social commentary, but an enduring archive of American memory. Each entry is a window into the war’s legacy, and a reminder that the stories we tell outlast the battles themselves.

10 MOVIES THAT DEFINED THE VIETNAM WAR ON THE BIG SCREEN

The Vietnam War cast a long shadow across one of the most fertile periods of American filmmaking, and has led filmmakers for the half-century since to reckon with its complicated legacy. These 10 films, assembled to mark the 50th anniversary of the fall of Saigon, range from indelible anti-war classics to Vietnamese portraits of resistance, capturing the vastness of the war’s still-reverberating traumas.

“The Big Shave” (1967)

The war was more than a decade in and some eight years from its conclusion when a 25-year-old Martin Scorsese made this six-minute short. In it, a man simply shaves himself before a sink and a mirror. After a few knicks and cuts, he doesn’t stop, continuing until his face is a bloody mess — a neat but gruesome metaphor to Vietnam.

“The Little Girl of Hanoi” (1974)

A young girl (Lan Hương) searches for her family in the bombed-out ruins of Hanoi in Hải Ninh’s landmark of Vietnamese cinema. It’s a work of wartime propaganda (it begins with the intro: “honoring the heroes of Hanoi who defeated the American imperialist B-52 bombing raid”) but also of aching humanity. Set against the December 1972 bombing raids on Hanoi, “The Little Girl of Hanoi” is cinema made in the very midst of war.

“Hearts and Minds” (1974)

Controversy greeted Peter Davis’ landmark documentary around its release, but time has only proved how soberly clear-eyed it was. Newsreel clips and homefront interviews are contrasted with the horrors on the ground in Vietnam in this penetrating examination of the gulf between American policy and Vietnamese reality. Its title comes from President Lyndon B. Johnson’s line, said when escalating the war, that “the ultimate victory will depend on the hearts and minds of the people who actually live out there.”

“The Deer Hunter” (1979)

It’s arguably the preeminent American film about the Vietnam War. No other movie more grandly or tragically charts the American evolution from innocence to disillusionment than Michael Cimino’s devastating epic about working-class friends (Robert De Niro, Christopher Walken, John Savage) from a Pennsylvania steel town drafted into war. The final sing-along scene to “God Bless America,” after their lives have irrevocably changed, remains a powerfully poignant gut punch.

“Apocalypse Now” (1979)

Francis Ford Coppola wagered everything he had on his masterpiece — and nearly lost it. “Apocalypse Now,” which transposes Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness” to the Vietnam War, is an epic of madness that teeters on the brink of hallucination. Shot in the Philippines and more faithful to Conrad than to Vietnam, “Apocalypse Now” doesn’t so much illuminate the chaos and moral confusion of the war as elevate it to grandiose nightmare.

“Platoon” (1986)

The 1980s saw a wave of Hollywood films about Vietnam, including “First Blood,” “Hamburger Hill,” “Good Morning Vietnam,” “Casualties of War” and “Born on the Fourth of July.” Foremost among them is the Oscar best picture-winning “Platoon,” which Oliver Stone wrote based on his own experiences as an infantryman in Vietnam. Widely acclaimed for its realism, Stone’s film remains among the most intensely vivid and visceral dramatizations of the war.

“Full Metal Jacket” (1987)

Stanley Kubrick should be more often thought of as the supreme anti-war moviemaker. His devastating World War I film “Paths of Glory” and the subversive satire “Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb” are classics in their own right. “Full Metal Jacket” carries those films’ themes of dehumanization into an even more brutal place. Split between the harrowing boot-camp tyranny of R. Lee Ermey’s drill instructor and the urban violence of the 1968 Tet Offensive, “Full Metal Jacket” fuses both ends of the war machine.

“Little Dieter Needs to Fly” (1997)

How former soldiers lived with their experience in Vietnam has been a subject of many fine films, from Hal Ashby’s “Coming Home” (1978) to Spike Lee’s “Da 5 Bloods” (2020). In Werner Herzog’s nonfiction gem, he profiles the astonishing story of German-American pilot Dieter Dengler. In the film, which Herzog later remade as 2007’s “Rescue Dawn” with Christian Bale, Dengler recounts — and sometimes reenacts — his experience being shot down over Laos, being captured and tortured and then escaping into the jungle.

“The Fog of War” (2003)

Not long after the turn of the century, former U.S. defense secretary and Vietnam War architect Robert S. McNamara sat for interviews with documentarian Errol Morris. The result is a chilling reflection on the thinking that led to one of American’s greatest follies. It’s not a mea culpa but a thornier and more disquieting rumination on how rationalized ideology can lead to the deaths of millions — and still not yield an apology. Of McNamara’s lessons, No. 1 is “empathize with the enemy.”

“The Post” (2017)

Steven Spielberg’s stirring film dramatizes the Washington Post’s 1971 publishing of the Pentagon Papers, a collection of classified documents that chronicled America’s 20-year involvement in Southeast Asia. While government analyst Daniel Ellsberg (a moving participant in “Hearts and Minds”) could be considered the hero of this story, “The Post” turns its focus to Washington Post publisher Katharine Graham (Meryl Streep) and the wartime role of the Fourth Estate.

12 TELEVISION SHOWS INFLUENCED BY THE VIETNAM WAR

The evening news brought the Vietnam War into American living rooms, but once the news was over, so was the war. Prime-time shows brought nary a mention of it as networks looked to bring uncontroversial content to the broadest possible audience. But the war simmered below the surface as subtext, and when enough years passed, television would finally take it on as a subject.

“Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C.” (1964-1969)

“Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C.” premiered on CBS six weeks after the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin resolution authorized U.S. combat troops in Vietnam, and the daft comedy was among the chief images of the military in American homes through the peak of U.S. involvement in 1969. Naturally, the show about a country rube in the Marine Corps never directly mentioned the war. But most of the real-life Marines who marched in its introduction would soon be fighting in Vietnam. Star Jim Nabors later said watching that intro was difficult, knowing some of those men had died.

“All in the Family” (1971-1979)

It would take “All in the Family” to bring the war into prime-time discourse. The Norman Lear-created CBS comedy owed its popularity to timely political bickering between cantankerous patriarch Archie Bunker (Carroll O’Connor) and his liberal-minded son-in-law Michael “Meathead” Stivic (Rob Reiner). Vietnam was the sole subject of a landmark 1976 episode where a draft-dodging fugitive friend of Michael’s comes to Christmas dinner, and an explosive argument ensues. “When the hell are you going to admit that the war was wrong?!” Michael shouts. A friend of Archie’s whose son died in the war shocks him by taking his son-in-law’s side.

“M*A*S*H” (1972-1983)

Set in the Korean War of the early 1950s, “M*A*S*H,” the CBS dramedy about wisecracking U.S. Army doctors, was among the most popular shows in the country during the Vietnam War’s final years. It was heavy with anti-military, anti-war sentiment, evoking the zeitgeist of a Vietnam-exhausted populace. “War isn’t Hell,” Hawkeye Pierce, played by Alan Alda, says in a typical line. “There are no innocent bystanders in Hell, but war is chock full of them.” (The Robert Altman film the show stemmed from deliberately minimized references to Korea to maximize its unspoken commentary on Vietnam.)

“The A-Team” (1983-1987)

Television’s first regular portrayal of Vietnam veterans came in the form of a cartoonish crew of daring mercenaries that reflected the era of Reagan and Rambo. NBC’s “The A-Team,” whose members included a mohawked-and-gold-chained Mr. T and a cigar-chomping George Peppard, were a “crack commando unit” who were innocent fugitives from military justice and worked as mercenaries pulling off weekly capers. Explosions and jumping cars abounded. In a fourth-season episode, the team returns to Vietnam for a job. Peppard’s Hannibal momentarily struggles with dark war memories before getting back to the lighthearted action.

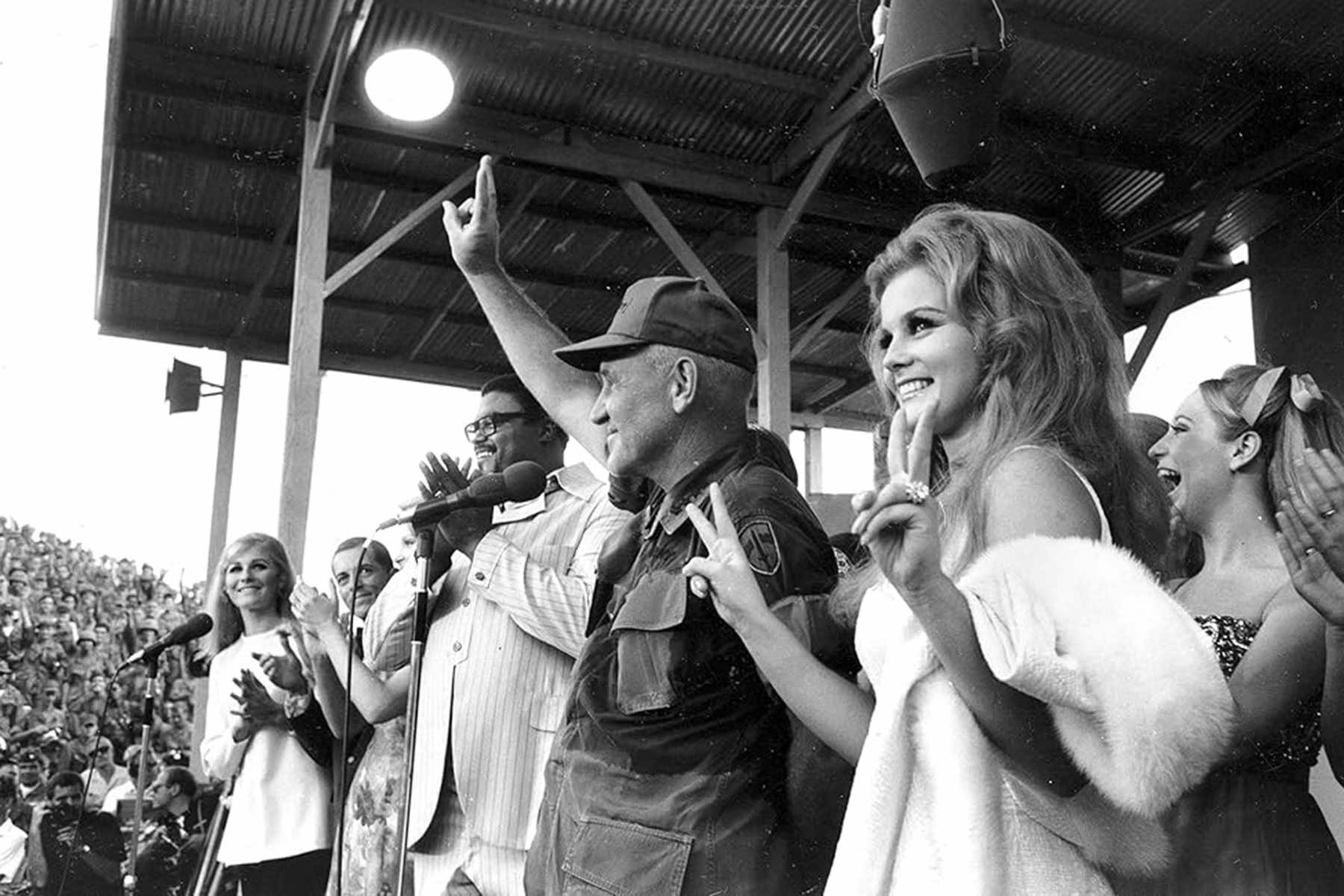

“The Welcome Home Concert” (1987)

HBO aired and helped organize a 1987 charity concert dubbed “Welcome Home” that billed itself as the warm celebration Vietnam War veterans never got upon their return. Performers included James Brown, Linda Ronstadt and Stevie Wonder. The July Fourth concert was not a militaristic affair, and had a hate-the-war, love-the-troops vibe. Some of the most anti-war songs of the ’60s were performed by artists like John Fogerty and Crosby, Stills & Nash. The event would be a harbinger of a wave of cultural nostalgia and reckoning as baby boomers began turning 40 and were in the mood to reflect.

“Tour of Duty” (1987-1990)

With “Tour of Duty,” the Vietnam War finally came to prime time. The CBS series that premiered in 1987 showed actual combat and the young men who fought and died in it. It might have been called “Platoon: The Series,” after the Vietnam film that had just won best picture at the Oscars. Surprisingly gory and gritty for a network show, it had all the hallmarks of the era’s many Vietnam movies. But executives seeking lower costs and higher ratings — which never came — eventually moved production from Hawaii to California and introduced romances and soapy plotlines typical of TV dramas.

“China Beach” (1988-1991)

And suddenly, there were two Vietnam series on TV. ABC’s “China Beach” was part-“M(asterisk)A(asterisk)S(asterisk)H,” part-“Grey’s Anatomy,” part-“Mad Men.” Set in a wartime evacuation hospital — the title was the Americans’ nickname for My Khe Beach in Đà Nẵng — it focused on Army medics and civilians. It was festooned with ’60s songs whose copyrights have kept the series off streaming services. Beloved by critics, “China Beach” made a star and a best-actress Emmy winner of Dana Delany, but never found a mass audience. With its cancellation, network TV depictions of the war would disappear for years.

“The Wonder Years” (1988-1993)

“The Wonder Years” was baby boomer nostalgia in its purest form. The ABC series, narrated by an adult Kevin Arnold (voiced by Daniel Stern, played as a child by Fred Savage), depicts his boyhood feelings and experiences with the backing of sentimental ’60s songs. The specter of Vietnam dominates its first season, which sees Kevin’s hero — the big brother of his neighbor and crush Winnie Cooper — die in the war. In a 2021 reboot, the story shifts to a Black family in Alabama, with narrator Dean Williams’ brother a returning Vietnam vet who faces racism at home.

“The ’60s” (1999)

The NBC miniseries “The ’60s” was a roundup of the decade’s cliches that by then had been well-established in movies and TV. The 1999 two-night event was billed as “the movie event of a generation.” Its subjects were three Chicago siblings who each go on very 1960s journeys. For Jerry O’Connell’s high-school quarterback character, that meant serving in Vietnam. He enlists in a gung-ho moment, but by the show’s second night, he’s back home with an Army jacket and long hair, drinking to bury his trauma. The show drew a big audience at a time when NBC was ratings king.

“This Is Us” (2016-2022)

The time-hopping, tear-jerking NBC family drama “This Is Us” used the Vietnam War to delve into the psyche of Jack Pearson (Milo Ventimiglia), who refused to talk about his experience as a soldier with his wife and kids before his premature death. In dual plotlines that run through its third season, with the emotional themes and folk-acoustic soundtrack that are hallmarks of “This Is Us,” Jack is shown enlisting to try to protect his drafted younger brother. Decades later, his son Kevin (Justin Hartley) travels to Vietnam to find out what happened to his father and uncle.

“The Vietnam War” (2017)

In a docuseries that ran over 10 nights on PBS, the Vietnam War got the same hallowed treatment Ken Burns brought nearly 30 years earlier to the Civil War. Burns and Lynn Novick’s “The Vietnam War” was not as soft or sentimental as his reputation might have suggested. It was a rare PBS show with a TV-MA rating, and its tone, with a modern soundtrack from composers Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, matched the messiness of the conflict. The show went to lengths to include a North Vietnamese perspective along with American and South Vietnamese vets and historians.

“The Sympathizer” (2024)

It took until 2024 before a fictional television show would attempt a Vietnamese perspective of the war’s end and its aftermath, though it brought mixed reactions from Vietnamese American viewers. HBO’s “The Sympathizer” was based on Viet Thanh Nguyen’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel. The first two episodes of the black-comic limited series depict a harrowing flight during the fall of Saigon. Actors of Vietnamese descent played most of its main roles, including lead Hoa Xuande. But much of the attention given to it — and its only Emmy nomination — went to Robert Downey Jr. for his portrayal of four different White American men.

11 NOTABLE SONGS ABOUT THE VIETNAM WAR

War, like love, has long inspired artists and musicians. That is especially true of the songs written in response to the Vietnam War during the countercultural movements of the 1960s and 1970s. The songs released in that time — and in the years that followed — sought to highlight the experiences of those affected by combat and in a period of societal upheaval.

“Saigon Bride,” Joan Baez (1967)

Based on a poem sent to Joan Baez by Nina Duschek, “Saigon Bride” is emblematic of ’60s folk music and tells the story of a solider who goes to war, leaving his wife behind. “How many dead men will it take / To build a dike that will not break?” she sings in her soft vibrato. “How many children must we kill / Before we make the waves stand still?”

“Đường Trường Sơn xe anh qua,” Văn Dung (1968)

Văn Dung’s “Đường Trường Sơn xe anh qua” (“The Truong Son Road Your Vehicles Passed Through”) is written about the Ho Chi Minh trail, an expansive system of paths and trails used by North Vietnam to bring troops and supplies into South Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos during the war. Dung wrote the song in 1968, when he arrived at the Khe Sanh front, about female youth volunteers. There are many wonderful covers of this one, too, including a theatrical rendition by Trọng Tấn.

“Fortunate Son,” Creedence Clearwater Revival (1969)

It may very well be the first song that comes to mind when the Vietnam War is brought up. Creedence Clearwater Revival’s three-time platinum “Fortunate Son” is a benchmark by which to compare the efficacy of all other protest anthems. Frontman John Fogerty wrote this one to highlight what he viewed as an innate hypocrisy: American leaders perpetuating war while protecting themselves from making the same sacrifices they asked of the public. “Yeah-yeah, some folks inherit star-spangled eyes,” he sings. “Hoo, they send you down to war, Lord.”

“I Should Be Proud,” Martha Reeves & the Vandellas (1970)

Martha Reeves & the Vandellas’ “I Should Be Proud” is conflicted. Soul singer Reeves embodies a narrator who learns her love has been killed in combat during the Vietnam War. Instead of being filled with pride for his sacrifice, she grieves. “But I don’t want no silver star,” she sings. “Just the good man they took from me.”

“Ca Dao Mẹ,” Trịnh Công Sơn (1970)

The Vietnamese singer-songwriter Trịnh Công Sơn has a rich catalog featuring a myriad of anti-war songs; selecting just one is a challenge. But “Ca Dao Mẹ” (“A Mother’s Lullaby”) is a clear standout. It details a mother’s sacrifice during wartime. In the last verse, the mother sings a lullaby to her child and also the young country. Vietnamese singer Khánh Ly does a lovely cover of it, too.

“Ohio,” Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young (1971)

On May 4, 1970, the Ohio National Guard opened fire on unarmed college students during a protest at Kent State University. Four students were killed, and nine others were injured. Not all of those hurt or killed were involved in the demonstration, which opposed the U.S. bombing of neutral Cambodia during the Vietnam War. Neil Young was sitting on a porch with David Crosby when he saw images of the horrific event in a magazine and decided to write a song about it. “What if you knew her and found her dead on the ground?” he sang.

“What’s Going On,” Marvin Gaye (1971)

There isn’t an emotion Marvin Gaye couldn’t perfectly articulate with his rich tone; the classic “What’s Going On” is no exception. The song was originally inspired by an act of police brutality in 1969 known as “Bloody Thursday”; when it got to Gaye, it was imbued with experiences gleaned from his brother, a Vietnam veteran. The message, of course, is timeless.

“Happy Xmas (War Is Over),” John Lennon, Yoko Ono, The Plastic Ono Band with the Harlem Community Choir (1971)

There isn’t a lot of overlap with Christmas songs and protest music, but John Lennon, Yoko Ono, the Plastic Ono Band and the Harlem Community Choir certainly knew how to get their message across with “Happy Xmas (War Is Over).” It’s a smart choice — combining the sweetness of a holiday tune with a message of unity — delivered with guitar, piano, chimes and, most effective of all, a children’s choir.

“Back to Vietnam,” Television Personalities (1984)

Formed the year punk broke — that’s 1977, two years after the end of the Vietnam War — English post-punk band Television Personalities are a cult favorite for their cheeky, ramshackle, clever pop songs, led by frontman Dan Treacy’s undeniable schoolboy charm. The final track on their 1984 album “The Painted Word,” however, tells a different story. “Back to Vietnam” describes an insomniac man experiencing wartime post-traumatic stress disorder, replete with the sounds of gunshots and screams.

“Agent Orange,” Sodom (1989)

German thrash metal band Sodom’s 1989 album “Agent Orange” put their extreme music on the map, even breaking into the Top 40 in their native country. Beyond its ferocious pleasures, the album centers on lead vocalist and principal songwriter Tom Angelripper’s fascination with the Vietnam War, leading with the opening title track. “Operation Ranch Hand / Spray down the death,” he releases a throaty scream.

“The Wall,” Bruce Springsteen (2014)

Dedicated fans of the Boss know “The Wall” is one Bruce Springsteen held onto for a while; he performed it at a 2002 benefit long before its official release on his 2014 album “High Hopes.” The song was inspired by a trip he took to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington. “This black stone and these hard tears,” he sings in the first verse, “are all I got left now of you.”

10 FICTION AND NONFICTION BOOKS INSPIRED BY THE VIETNAM WAR

Vietnam has been called the first “television” war. But it has also inspired generations of writers who have explored its origins, its horrors, its aftermath and the innate flaws and miscalculations that drove the world’s most powerful country, the U.S., into a long, gruesome and hopeless conflict.

“The Quiet American,” Graham Greene (1955)

British author Graham Greene’s novel has long held the stature of tragic prophecy. Alden Pyle is a naive CIA agent whose dreams of forging a better path for Vietnam — a “Third Force” between communism and colonialism that existed only in books — leads to senseless destruction. “The Quiet American” was released when U.S. military involvement in Vietnam was just beginning, yet anticipated the Americans’ prolonged and deadly failure to comprehend the country they claimed to be saving.

“The Things They Carried,” Tim O’Brien (1990)

The Vietnam War was the last extended conflict waged while the U.S. still had a military draft, and the last to inspire a wide range of notable, first-hand fiction — none more celebrated or popular than O’Brien’s 1990 collection of interconnected stories. O’Brien served in an infantry unit in 1969-70, and the million-selling “The Things They Carried” has tales ranging from a soldier who wears his girlfriend’s stockings around his neck, even in battle, to the author trying to conjure the life story of a Vietnamese soldier he killed. O’Brien’s book has become standard reading about the war and inspired an exhibit at the National Veterans Art Museum in Chicago.

“Matterhorn,” Karl Marlantes (2009)

Karl Marlantes, a Rhodes scholar and decorated Marine commander, fictionalized his experiences in his 600-plus page novel about a recent college graduate and his fellow members of Bravo Company as they seek to retake a base near the border with Laos. Like “The Quiet American,” “Matterhorn” is, in part, the story of disillusionment, a young man’s discovery that education and privilege are no shields against enemy fire. “No strategy was perfect,” he realizes. “All choices were bad in some way.”

“The Sympathizer,” Viet Thanh Nguyen (2015)

Viet Thanh Nguyen was just 4 when his family fled Vietnam in 1975, eventually settling in San Jose, California. “The Sympathizer,” winner of the Pulitzer Prize in 2016, is Nguyen’s first book and high in the canon of Vietnamese American literature. The novel unfolds as the confessions of a onetime spy for North Vietnam who becomes a Hollywood consultant and later returns to Vietnam fighting on the opposite side. “I am a spy, a sleeper, a spook, a man of two faces,” the narrator tells us. “Perhaps not surprisingly, I am also a man of two minds.”

“The Mountains Sing,” Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai (2020)

Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai was born in North Vietnam in 1973, two years before the U.S. departure, and was reared on stories of her native country’s haunted and heroic past. Her novel alternates narration between a grandmother born in 1920 and a granddaughter born 40 years later. Together, they take readers through much of 20th century Vietnam, from French colonialism and Japanese occupation to the rise of Communism and the growing and brutal American military campaign to fight it. Quế Mai dedicates the novel to various ancestors, including an uncle whose “youth the Vietnam War consumed.”

“The Best and the Brightest,” David Halberstam (1972)

As a young reporter in Vietnam, David Halberstam had been among the first journalists to report candidly on the military’s failures and the government’s deceptions. The title of his bestseller became a catchphrase and the book itself a document of how the supposedly finest minds of the post-World War II generation — the elite set of advisers in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations — could so badly miscalculate the planning and execution of a war and so misunderstand the country they were fighting against.

“Fire in the Lake,” Frances FitzGerald (1972)

Frances FitzGerald’s celebrated book was published the same year and stands with “The Best and the Brightest” as an early and prescient take on the war’s legacy. Fitzgerald had reported from South Vietnam for the Village Voice and The New Yorker, and she drew upon firsthand observations and deep research in contending that the U.S. was fatally ignorant of Vietnamese history and culture.

“Dispatches,” Michael Herr (1977)

Michael Herr, who would eventually help write “Apocalypse Now,” was a Vietnam correspondent for Esquire who brought an off-hand, charged-up rock ‘n’ roll sensibility to his highly praised and influential book. In one “dispatch,” he tells of a soldier who “took his pills by the fistful,” uppers in one pocket and downers in another. “He told me they cooled out things just right for him,” Herr wrote, “that he could see that old jungle at night like he was looking at it through a starlight scope.”

“Bloods,” Wallace Terry (1984)

A landmark, “Bloods” was among the first books to center the experiences of Black veterans. Former Time magazine correspondent Wallace Terry compiled the oral histories of 20 Black veterans of varying backgrounds and ranks. One interviewee, Richard J. Ford III, was wounded three times and remembered being visited at the hospital by generals and other officers: “They respected you and pat you on the back. They said, ‘You brave and you courageous. You America’s finest. America’s best.’ Back in the states, the same officers that pat me on the back wouldn’t even speak to me.”

“A Bright Shining Lie,” Neil Sheehan (1988)

Halberstam’s sources as a reporter included Lt. Col. John Paul Vann, a U.S. adviser to South Vietnam who became a determined critic of American military leadership and eventually died in battle in 1972. Vann’s story is told in full in “A Bright Shining Lie,” by Neil Sheehan, the New York Times reporter known for breaking the story of the Pentagon Papers and how they revealed the U.S. government’s long history of deceiving the public about the war. Winner of the Pulitzer in 1989, “A Bright Shining Lie” was adapted into an HBO movie starring Bill Paxton as Vann.