The House bill, called the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, was passed by a vote of 410-4 on February 26, after the Senate passed the bill unanimously last year. The legislation, if signed into law by President Trump, will end more than a century of effort to make lynching a federal crime.

As Erin Logan reported, this was something that Congress had failed to do for over 120 years. Lawmakers in the first half of the 20th Century tried nearly 200 times to address lynching on a federal level. Although seven presidents supported such efforts, none were successful.

The first efforts to address this lawlessness on the federal level came in 1870, when President Ulysses S. Grant approved legislation to subdue the actions of white-supremacist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan. Michael J. Pfeifer, history professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, told The Washington Post in an email that legislative failure to federally penalize assailants was largely because of Southern lawmakers’ stonewalling.

“Asserting a doctrine of ‘states’ rights,’ Southern Democratic senators consistently thwarted federal anti-lynching legislation over the decades,” Pfeifer said. “So although federal anti-lynching legislation enjoyed majority support in the House in the 1920s and ’30s, through the filibuster and other means, Southern Democrats were able to block federal anti-lynching legislation.”

The topic of lynchings in America has been renewed recently by Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative and author of the book Just Mercy, which has been made into a movie. Stevenson began his career by defending people on death row, primarily in Alabama. Here is how he explains the connection between that work and his efforts to document the history of lynchings in this country. Stevenson says that slavery didn’t end in 1865, it just evolved.

There is a line from slavery through racial terrorism, through segregation, that is evident in what we see in our criminal justice system today. I am persuaded that we really won’t eliminate the problems of discrimination in the criminal justice system, in the education system, in the employment system until we change the narrative of racial difference that we have all accepted… These acts of humiliation and degradation created this desensitizing to victimization. We are indifferent to evidence of bias or discrimination. We are indifferent to innocent people being wrongly condemned on death row for thirty years. I think there is a historical root to that silence.

One of the results of Stevenson’s work is a report titled “Lynchings in America,” which documents over 4,000 instances of the racial terror between 1877 and 1950 predominantly (but not exclusively) in the South.

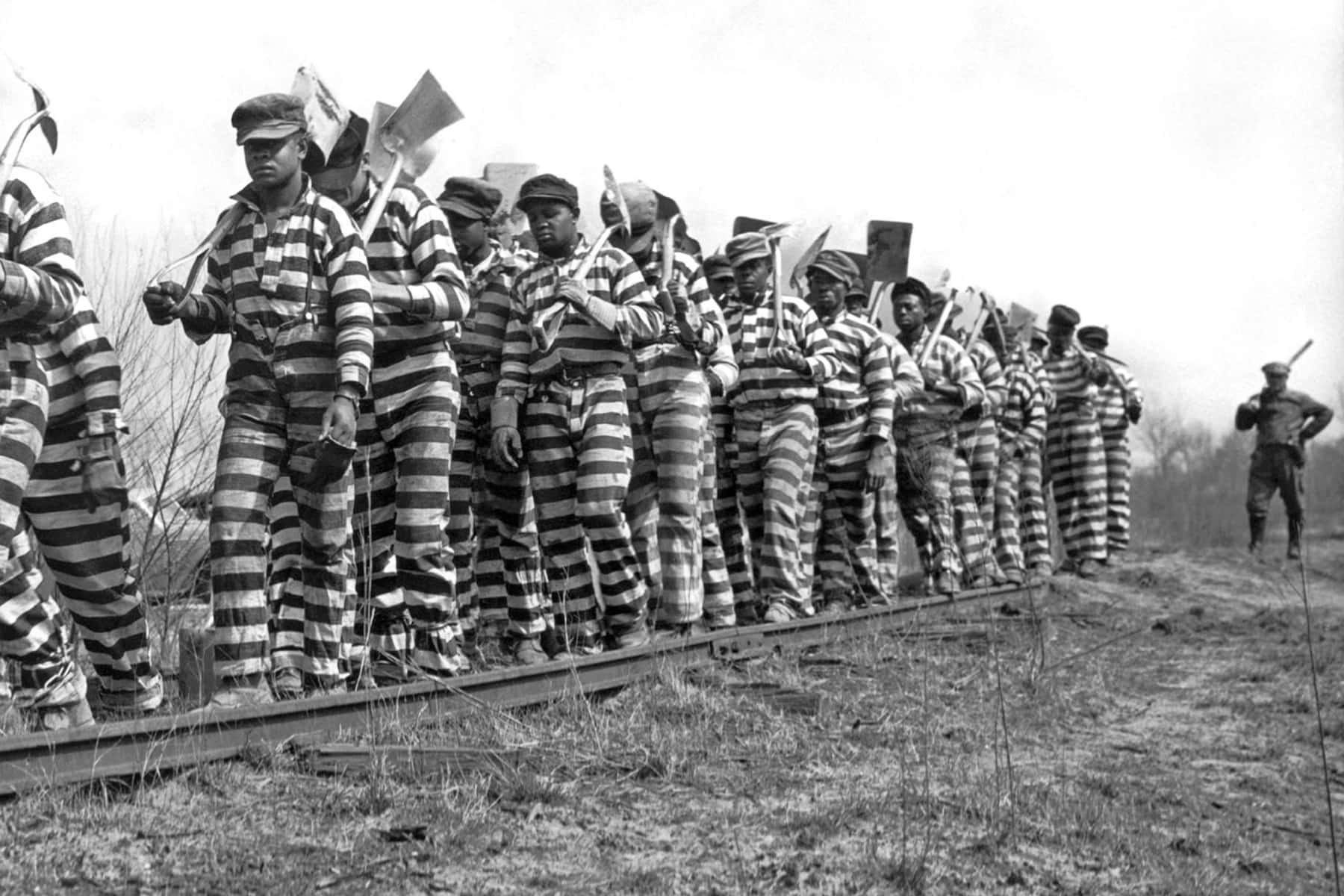

Lynching in America makes the case that lynching of African Americans was terrorism, a widely supported phenomenon used to enforce racial subordination and segregation. Lynchings were violent and public events that traumatized black people throughout the country and were largely tolerated by state and federal officials. This was not “frontier justice” carried out by a few marginalized vigilantes or extremists. Instead, many African Americans who were never accused of any crime were tortured and murdered in front of picnicking spectators (including elected officials and prominent citizens) for bumping into a white person, or wearing their military uniforms after World War I, or not using the appropriate title when addressing a white person. People who participated in lynchings were celebrated and acted with impunity.

One way we can re-sensitize ourselves to this history is to listen to the stories of people like Shirah. Her great grandfather was lynched in Shreveport, Louisiana. As part of Caddo Parish, it represents the community with the second highest number of lynchings in the country. That begins to bring this all home to me because I grew up in the town of Longview, Texas, which is just 60 miles west of Shreveport. Because none of these stories were included in the history classes I attended, I was interested in learning more about what happened in the area around my hometown.

One of the things I learned is that there was a race riot in the town of Longview back in 1919. It was actually part of what has become known as the “red summer,” which included anti-black white supremacists attacks in more than three dozen cities. Here is how the Texas State Historical Association describes the incidents that led to the riot in Longview.

Racial tension was especially high immediately before the riot because two locally prominent black leaders, Samuel L. Jones and Dr. Calvin P. Davis, had urged black farmers to avoid local white cotton brokers and sell directly to buyers in Galveston. Then an article in the July 10 issue of the Chicago Defender…described the death of a young black man, Lemuel Walters, in Longview. The article reported that Walters and an unnamed white woman from Kilgore, Texas, were in love and quoted her as saying they would have married if they had lived in the North. Walters, according to the article, was safely locked in the Gregg County Jail until the sheriff willingly handed him over to a white mob that murdered him on June 17. Jones, a teacher in the Longview school system and a local correspondent for the Chicago Defender, was held responsible for the article, and on Thursday, July 10, he was accosted and beaten, supposedly by two brothers of the Kilgore woman.

The congressman who currently represents the district that includes Longview is Republican Louie Gohmert. He is one of the four House members who voted against the anti-lynching bill on Wednesday. History is alive and well in northeast Texas.

I hope you’ll forgive me for writing so much about my hometown. But this is exactly what Stevenson is suggesting that we all need to do. In order to shed our indifference to the way that slavery has evolved, we need to unlock the silence about our own past by putting it into human terms.

I grew up in a community that was scarred by what happened to people like Lemuel Walters, Samuel Jones, and Shirah’s great grandfather. Their deaths are examples of the kind of terrorism that was designed to instill fear as a way to entrench white supremacy. That legacy lives on today, most notably in our criminal justice system.

Nаncy LеTоurnеаu

Library of Congress

Originally published as Slavery didn’t end in 1865. It just evolved.