On November 19, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln delivered one of the best known speeches in American history, at the dedication of the Soldiers National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

This essay is part of a series of opinion pieces. Each one is no longer than 272 words, the length of Gettysburg Address, and responds with a view of how Lincoln’s spoken ideas in Gettysburg are relevant to America in 2017.

The barque of state is pitching in roiled seas. The Congress is in intransigent gridlock. Government officers institute few positive programs but undo past common good advances. The president has engaged in conduct not seen in prior presidencies and a current investigation seeks to determine whether his election campaign unlawfully colluded with Russian agents. Concern exists that the president will abuse his powers of office in violation of the Constitution.

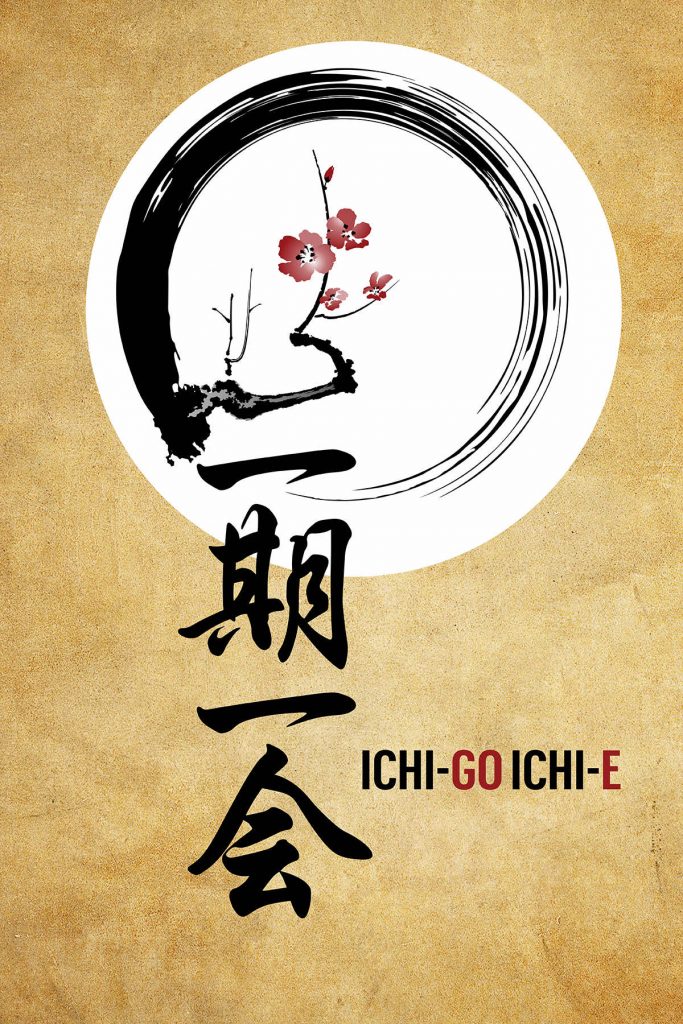

Our nation was ripped asunder during the Civil War. Lincoln intended his Gettysburg Address to honor the soldiers who “gave the last full measure of devotion” and to summon the will of the people to “highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth.” This call, thankfully, still resonates to summon us to protect our freedoms.

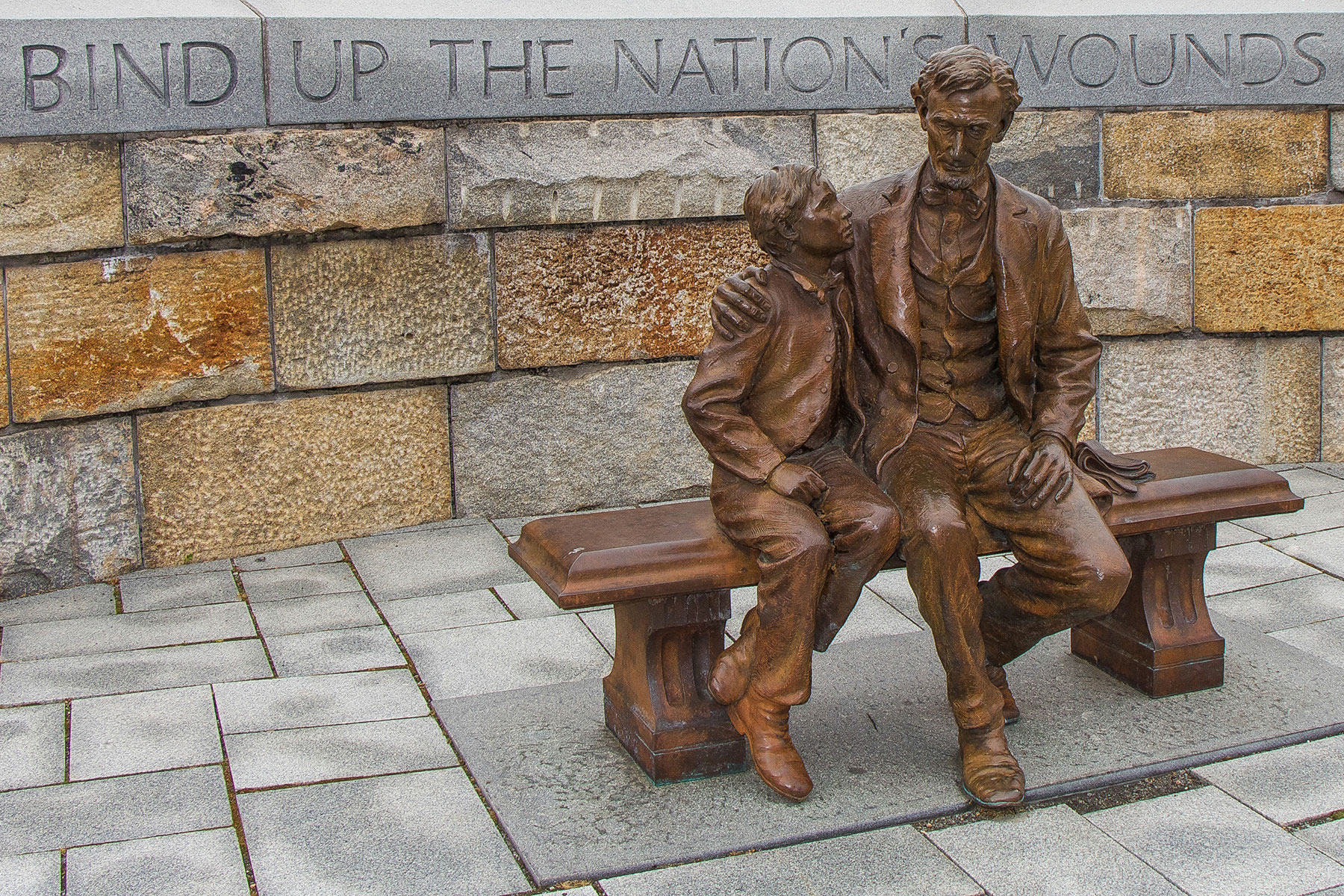

Violence by the white supremacists and by the antifa deserve condemnation. Lincoln posited in his Lyceum Address, “There is no grievance that is a fit object of redress by mob law.” He warned of danger from the man who “thirsts and burns for distinction” whose ambition stretches beyond the constitution and stated it “will require the people to be united with each other, attached to the government and laws and generally intelligent, to successfully frustrate his designs.” In his Second Inaugural Address, Lincoln noted that “fervently do we pray to God” for the war to end and advocated with “charity for all” to “bind up the nation’s wounds.”

Pray and bind up wounds.

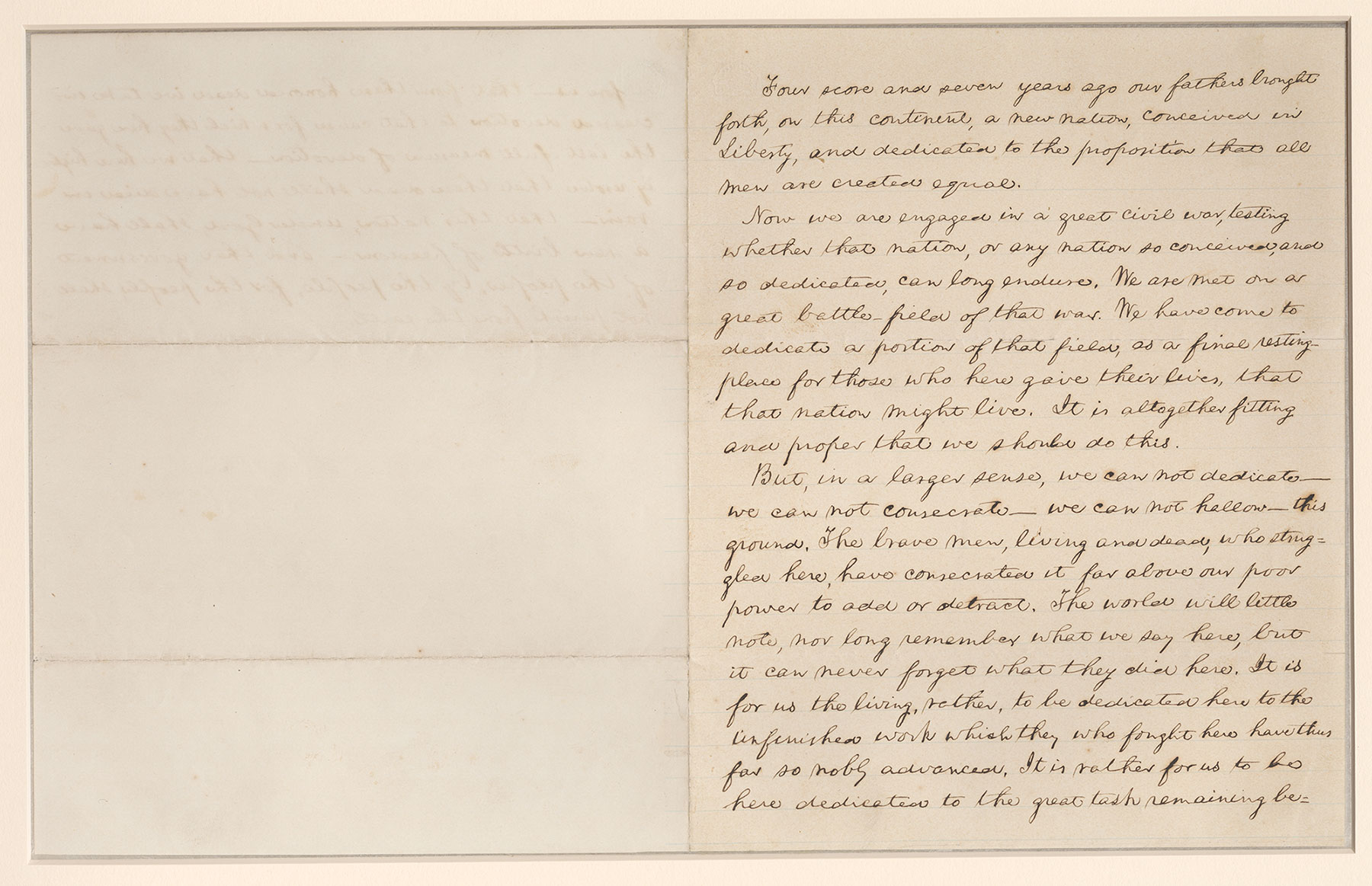

Lincoln's Gettysburg Address (The Bancroft Version)

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives, that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate, we can not hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they here gave the last full measure of devotion – that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Cornell University Library’s copy of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address is one of five known copies in Lincoln’s hand. Written out by President Lincoln at the request of U.S. historian, George Bancroft, this copy, the fourth that Lincoln composed, is known as the Bancroft Copy.

E. Michael McCann was the District Attorney of Milwaukee County from 1969 to 2007, and nation’s longest serving district attorney.