Our journey began in America when I was 6 years old. When my mother, father, brother, and myself immigrated over, our status simply read “Resident Alien.” Coming from a small and humble faming town in Northern India, this was probably an improvement from the life that we would have led had we stayed, or was it? It can be concluded that this is probably the mindset of nearly every immigrant. The idea that this American Dream will lead to a better life.

The year was 1982 when we moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, a small manufacturing town, built on beer and blue collar labor. Definitely, not as populated as India, but everything in America seemed so big – the people, the buildings, and the promise. Little did we know that in order the fulfill this dream there would be sacrifices.

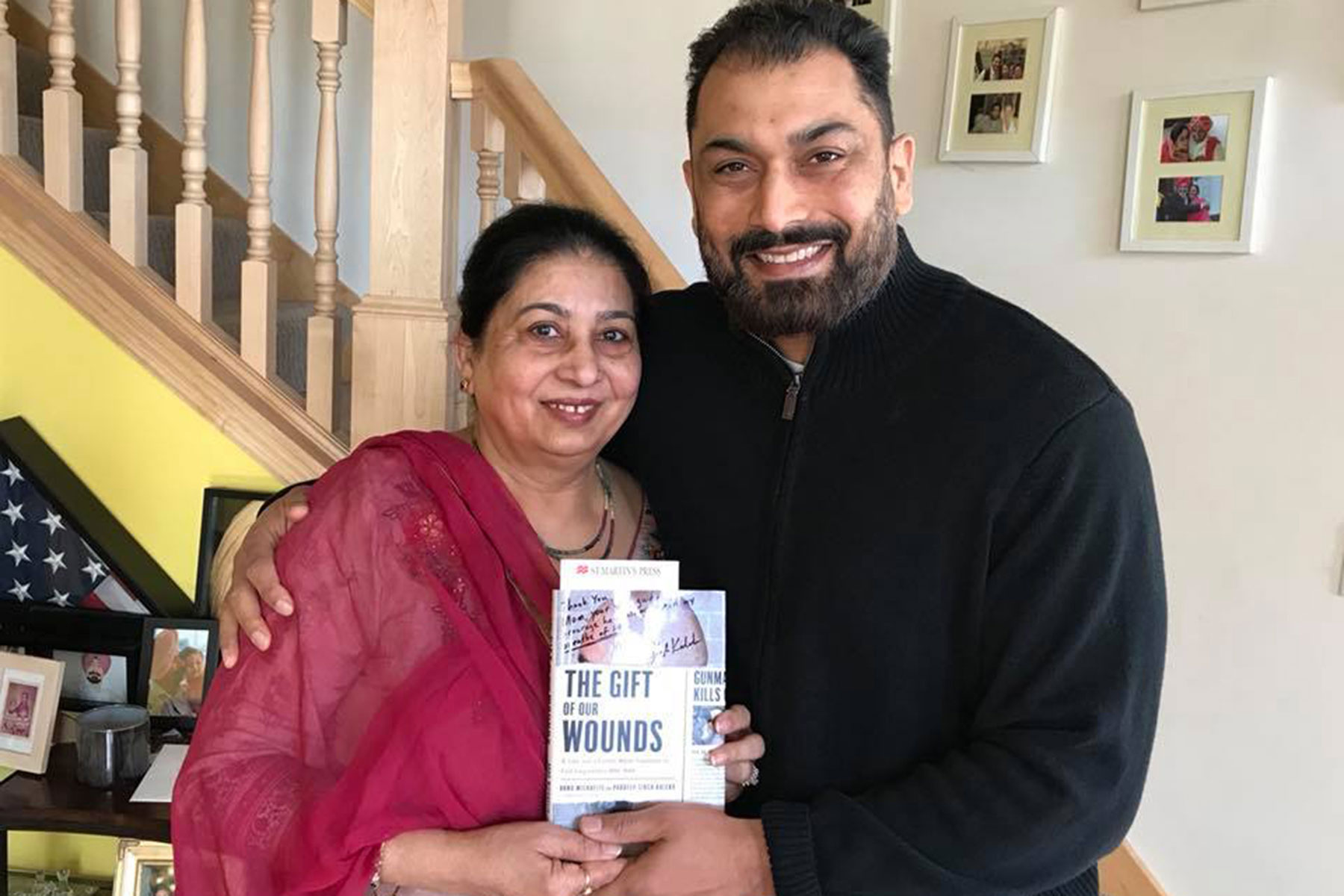

So we assimilated, our spiritual practices and our cultural heritage took a back seat to become part of the American quilt. I recall a conversation that my mother had with our first babysitter: “don’t allow my kids to speak Punjabi (our native language), teach them English please.”

Back then, justification of loss was “the melting pot” belief that we all lose a bit of our old culture to gain a new one.

Our family wanted to simply be accepted as any other American family. I was a child longing for acceptance and identity. To accomplish this, I recall wearing many different masks.

My parents had expectations that were so different from the new society we found ourselves in. I was not white enough, not black enough, not Latino enough, not Asian enough, just not enough. Finally, I thought to mix in I could be American enough, only to discover that we were not really nor could we ever be American enough.

Growing up I felt that this American Dream was never really meant for people like us.

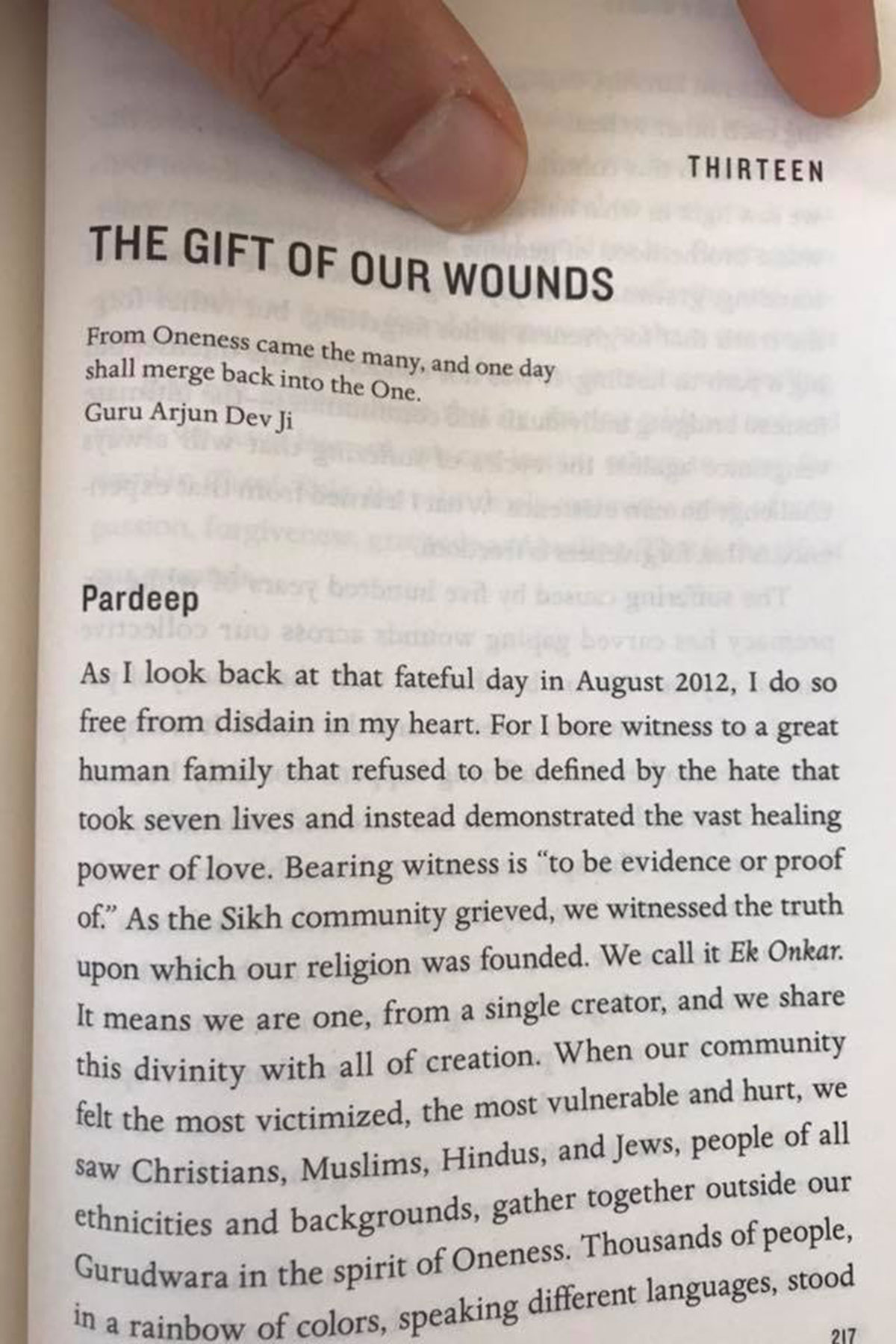

It was a message that could have been solidified after The Sikh Temple of Wisconsin attack on August 5, 2012. That day an ex-military affiliated white supremacist named Wade Page gunned down six immigrant Americans in cold blood while they attended prayer, before committing suicide himself.

One of the people killed was my father, a turban wearing American who tried to stop a gunman with the only weapon he had at his disposal, a butter knife. After this gun vs. knife fight, the shooter killed himself before he could be taken into custody. He did not have to answer for his actions, nor did he have to stand trial. Where was the justice in all of this?

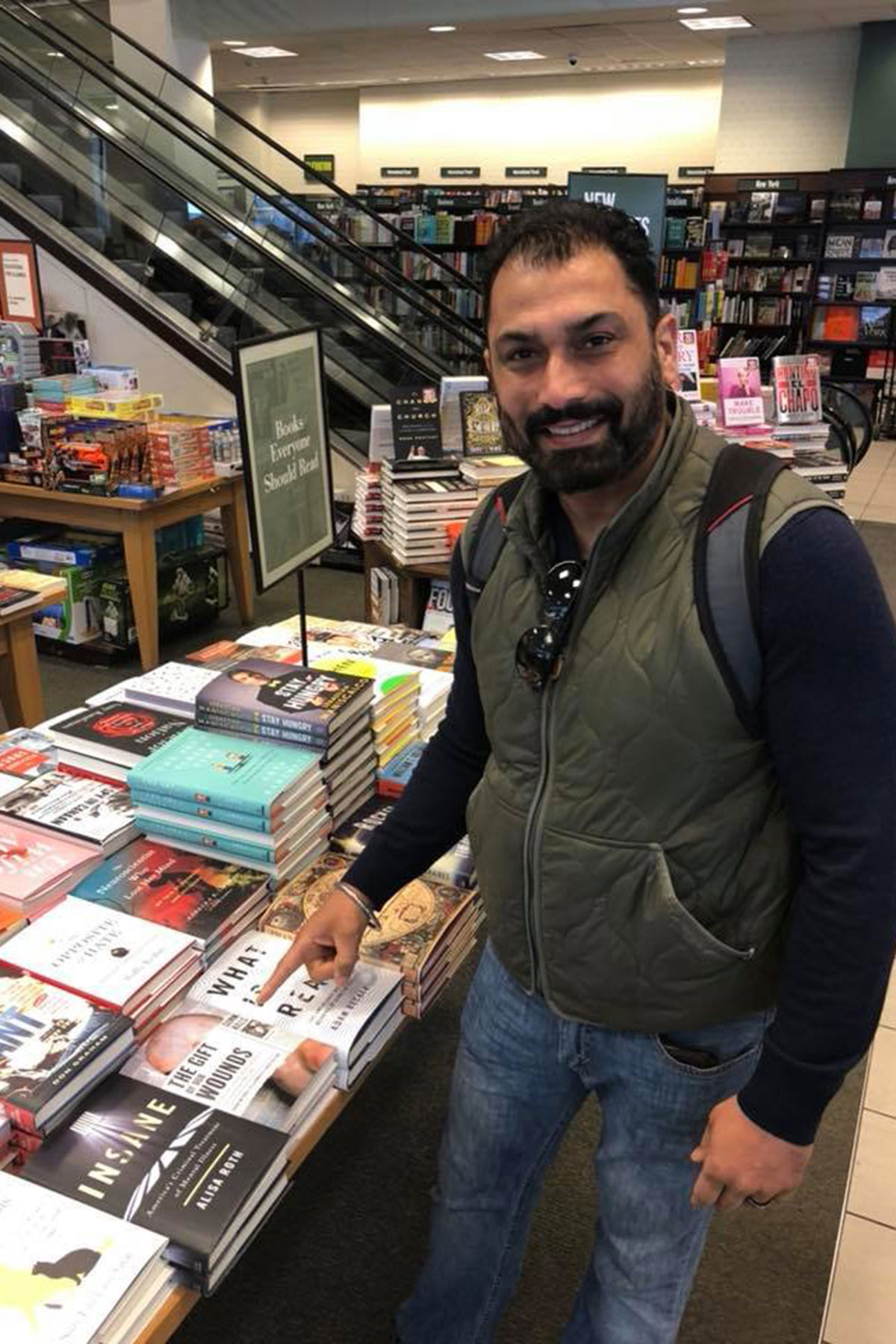

The powerful story of a friendship between two men, one Sikh and one skinhead, that resulted in an outpouring of love and a mission to fight against hate.

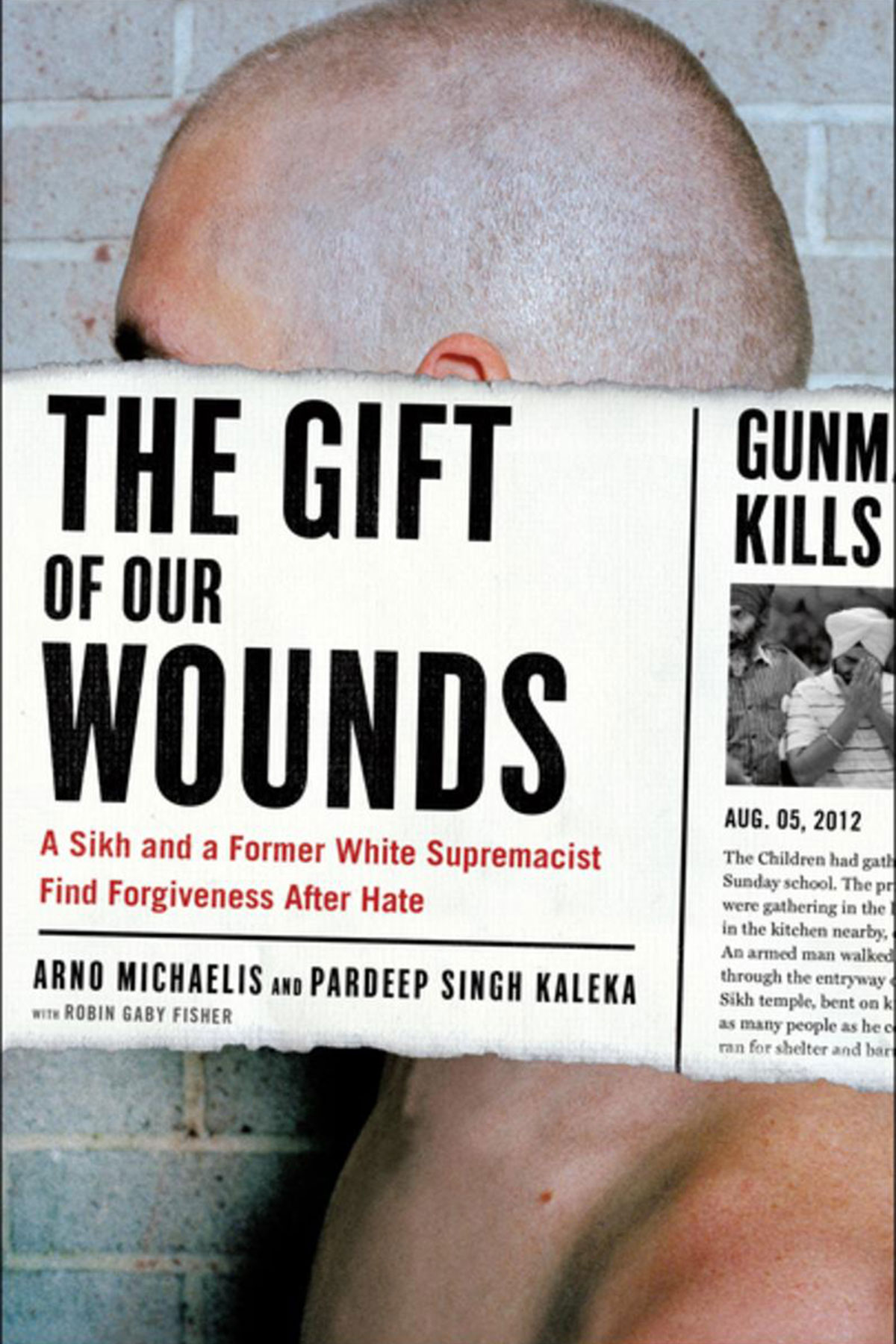

Our new book, The Gift of Our Wounds: A Sikh and a Former White Supremacist Find Forgiveness After Hate, explores that question and many more, such as immigration, white supremacy, culture, Isolation, suffering, identity, masculinity, mass shooting, policing, education, mental health, prevention, intervention, survivorship, gun culture, forgiveness, compassion, and empathy.

While there are many books that explore these topics, this is the first one that explores it from the first person narrative of a former white supremacist, Arno Michaelis, and an immigrant Sikh American, Pardeep Singh Kaleka. Both of us exploring our own personal journeys intersecting the complications of Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

In these divisive times, two men from drastically different backgrounds have come together on a mission to stop hate. Michaelis and Kaleka, with Robin Gaby Fisher, tell the remarkable story of how their friendship grew out of a horrific hate crime.

This gut-wrenching book provides a vital understanding of how to combat racism and white supremacists in order to build an inclusive society based on unity and respect.

When I first met Arno, our focus was to transform this tragedy in the spirit of resilience by embodying the Sikh practice of “Chardi Kala, relentless optimism to bring about peace and prosperity for all.” Hate begets suffering and suffering begets hate.

This cycle continues until we all have the courage to stand up against it and really reflect on our own capacity to hate. While we understand that standing up to hate looks different in different circumstances, for us this looked like a campaign to transform suffering into one of acknowledgement, healing, and connection.

At the time of the attack, Arno, founder of one of the world’s largest skinhead organizations, had left his racist life behind. When he learned Page came from the same skinhead world he used to live in, he felt a wave of guilt and an immediate need to take action.

Healing happens not because we are simply inspired, but instead when we are committed. The 2012 mass murder at the Sikh Temple was one of the deadliest committed by an affiliated white supremacist in nearly 50 years.

In 1963, four little girls endured the impact of a bomb intended for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. At that time, the FBI declared that the Klan was behind the attack, but the killers were not brought to justice until 13 years later.

That lack of immediate justice propelled the Civil Rights Movement into full force, passing the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts a few years later. Present day healing work is the continuation of this same spirit of commitment to equality, fairness, and dignity for all. Work that began long ago begs the same question today: can we heal from the backdrop of white supremacy?

Pardeep, devastated by his father’s death and infuriated by the attack, was trying to make sense of what happened. His search for answers led him to email Arno. The two men met and connected on a deep level. That first meeting planted a powerful seed. As Arno puts it, “A brown Sikh and a former racist skinhead, together, talking about unity and oneness.”

Arno and Pardeep went on to form Serve 2 Unite, an organization that works to create inclusive, compassionate, and nonviolent climates in schools and communities. That Arno and Pardeep were able to become friends and allies despite the extreme differences in their backgrounds is an example of how to bridge cultural divides.

It is not easy to read how Arno became a skinhead and the stories of his brutality. Pardeep’s account of the attack on his temple brings the full force of that tragedy to light. The lessons and awareness that come from Arno’s and Pardeep’s stories are invaluable. Readers will be inspired by their strength and vision for a better world.

Over the past 6 years, Arno and I have been able to travel from one American small town to another across the country. We have repeatedly talk about the issue that seems universally pressing in these town halls, tensions caused by the current demographic change.

It is this same fear that the current federal administration was able to exploit to win the last election. It is this same fear that is giving rise to global white nationalism, and justification for anti-immigrant thinking and policies.

During our time of working together, Arno and I have met countless survivors and perpetrators of violence from across the world. Many of them were going through their own private journeys of pain, while working to create very public campaigns of healing and reconciliation.

The path of healing is forged by bricks of forgiveness and compassion, and concludes when we step out from under the shadow of white supremacy and come together in healing.

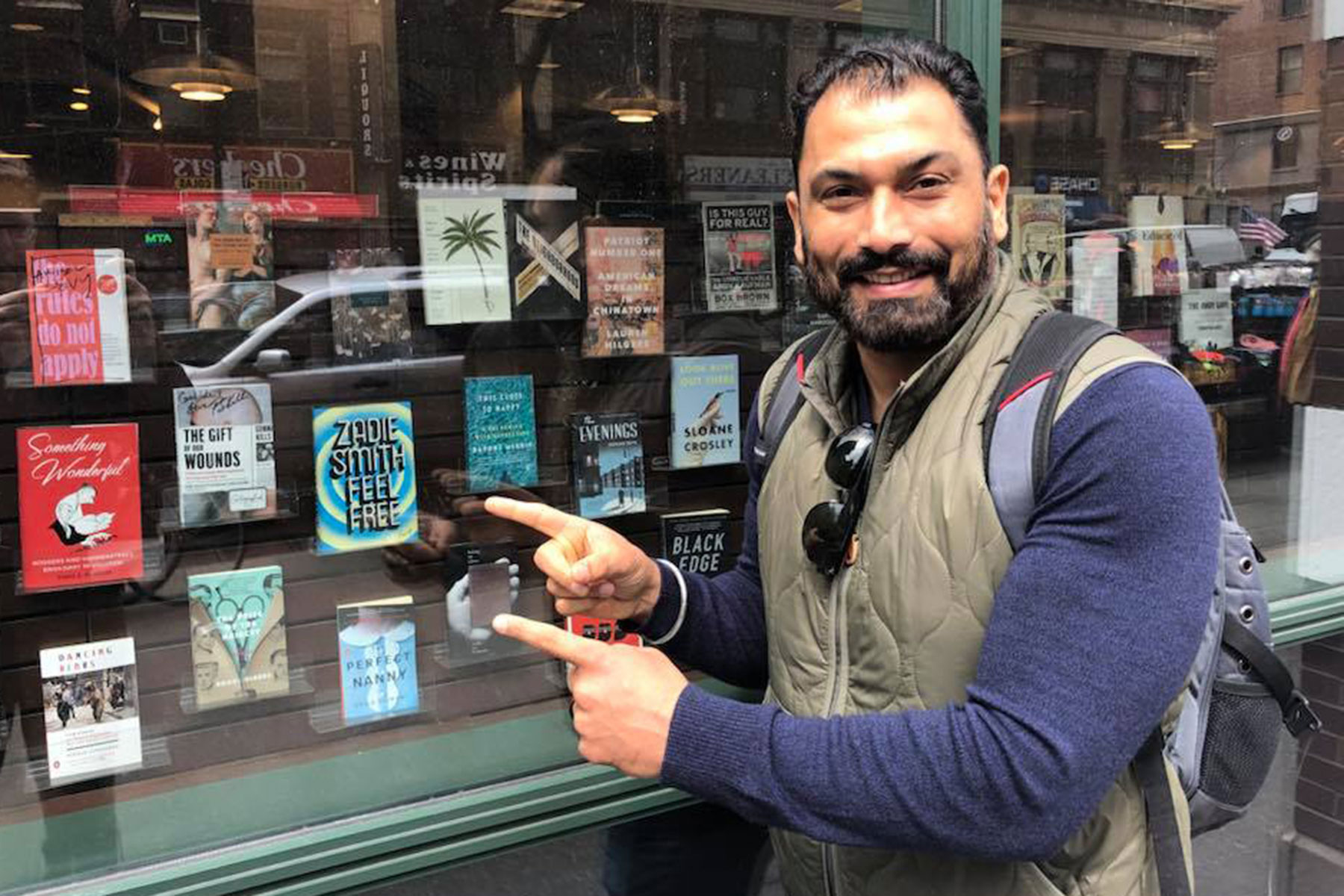

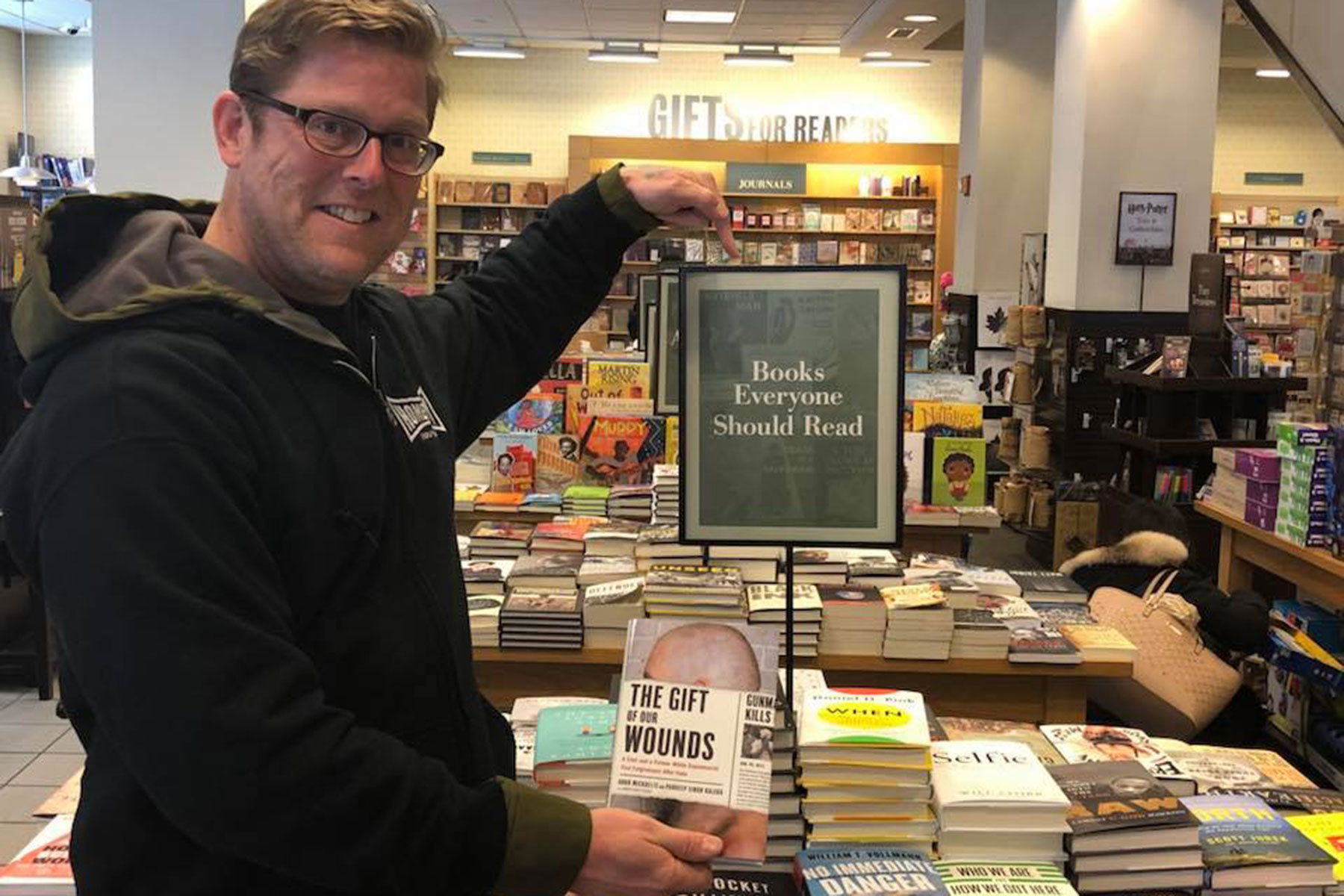

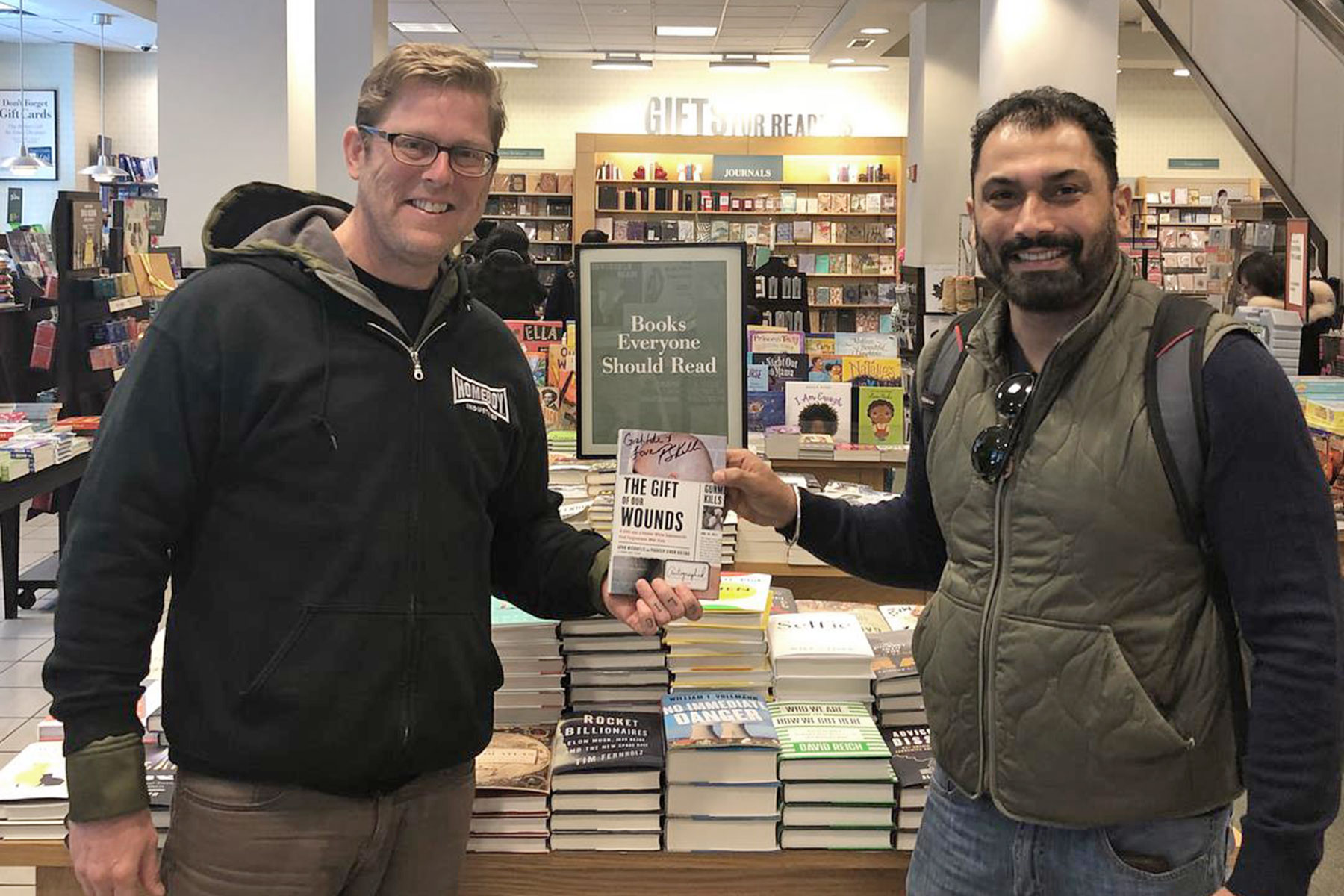

© Photo

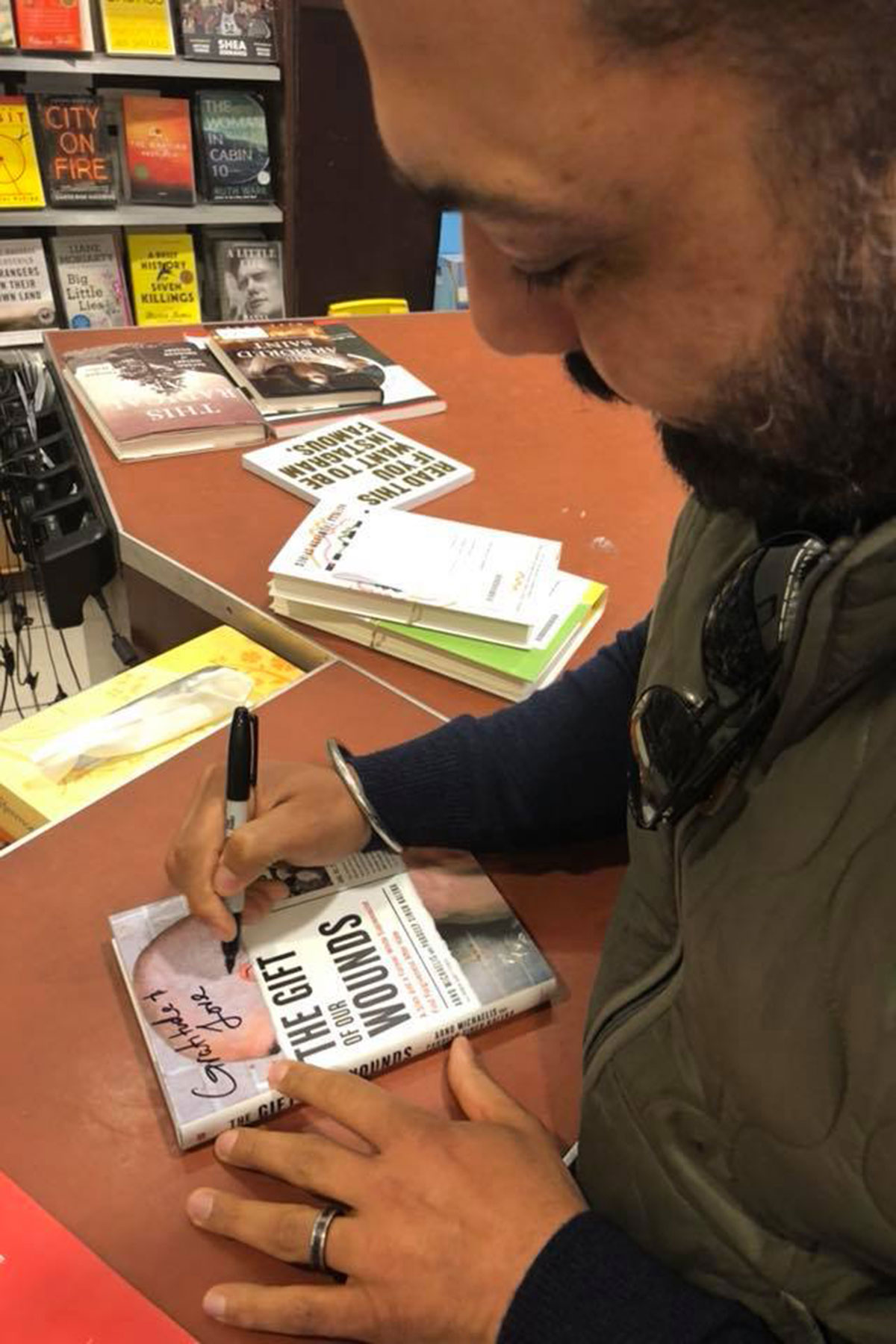

Arno Michaelis and Pardeep Singh Kaleka.